The Netherlands made contact with the Indonesian archipelago in the 16th century. Over three hundred years of contact with the Dutch gave rise to a population of Indo-Europeans—Dutch citizens sharing both European and Asian ancestry.

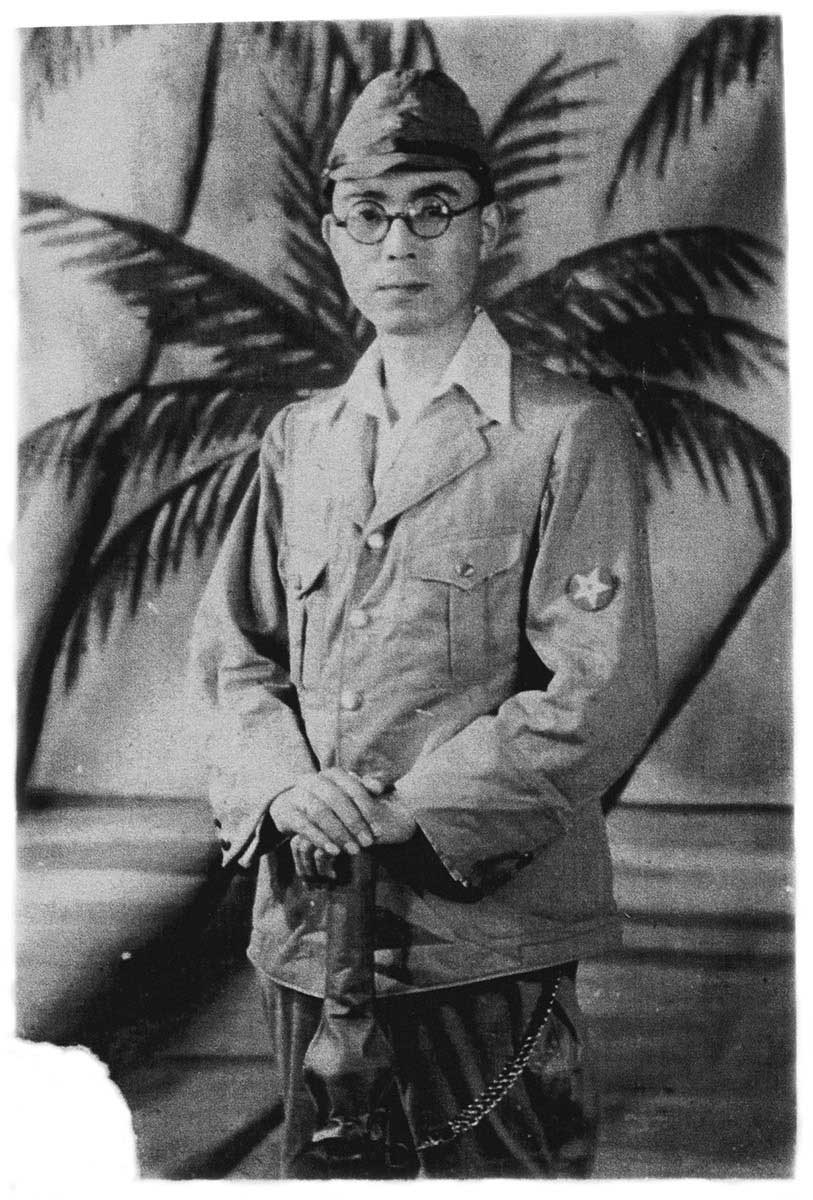

With the introduction of Dai-Toa Kyoeiken (The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere) and under the pretext of freeing Asia from European power, Japan attacked and occupied the Netherlands East Indies in 1942.

For the next three-and-a-half years, Java, Sumatra, Celebes and other islands were ruled by the Japanese military administration, with over 360,000 Japanese stationed in the Indies throughout that period. Not only were the men in military service in Royal Netherlands Indies Army or Royal Navy interned in POW camps, most of Dutch civilian men were also interned in Japanese civilian camps.

With their fathers, brothers and husbands interned during the war, the women and children were left to fend for themselves. Forced to search for a livelihood, many Indo-European women found work in Japanese offices, cafes or restaurants. In many cases, their encounters with the Japanese occupiers led to intimate relationships and births. While some women saw their relationships as consensual and long-term commitments, others reported having entered into such relationships against their will. The number of Japanese offspring born during the war were estimated to be at least 10,000* or approximately between 30,000 and 40,000** in Indonesia, but there is no concrete number even now.

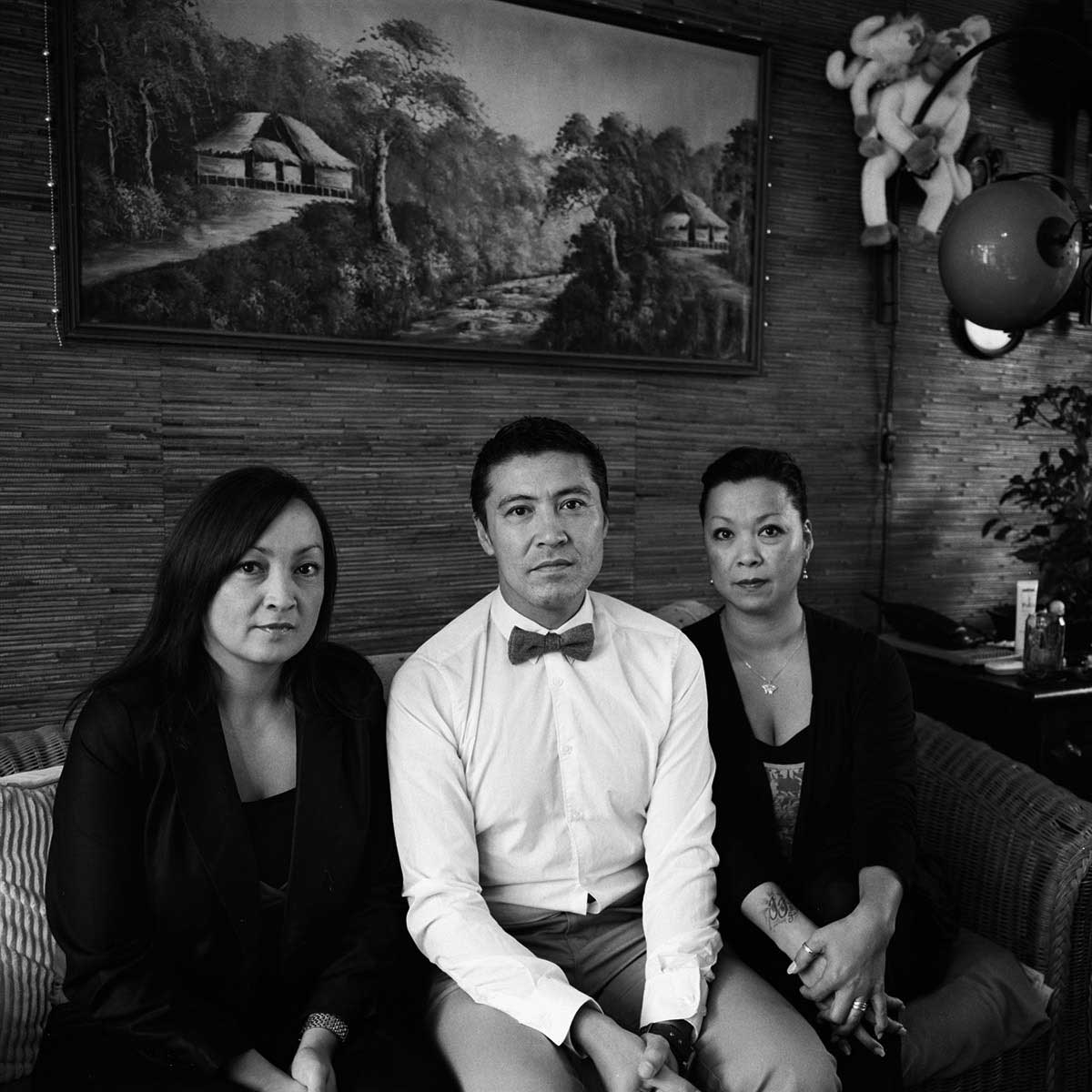

After the Japanese capitulation, Indonesia declared its independence. However, the Netherlands did not recognise the independence of its former colony. Dutch citizens and Indo-Europeans moved to so-called “Bersiap” camps to avoid attacks by Indonesian revolutionary groups, who were armed with Japanese weapons. This was the beginning of the four-year decolonisation period followed by large-scale military operations by the Netherlands, namely the Police Actions. Throughout this period, the mothers of children who had been fathered by Japanese men often felt ostracised from their communities. Consequently, many women and their families decided to keep quiet about their experiences and their children’s Japanese parentage.

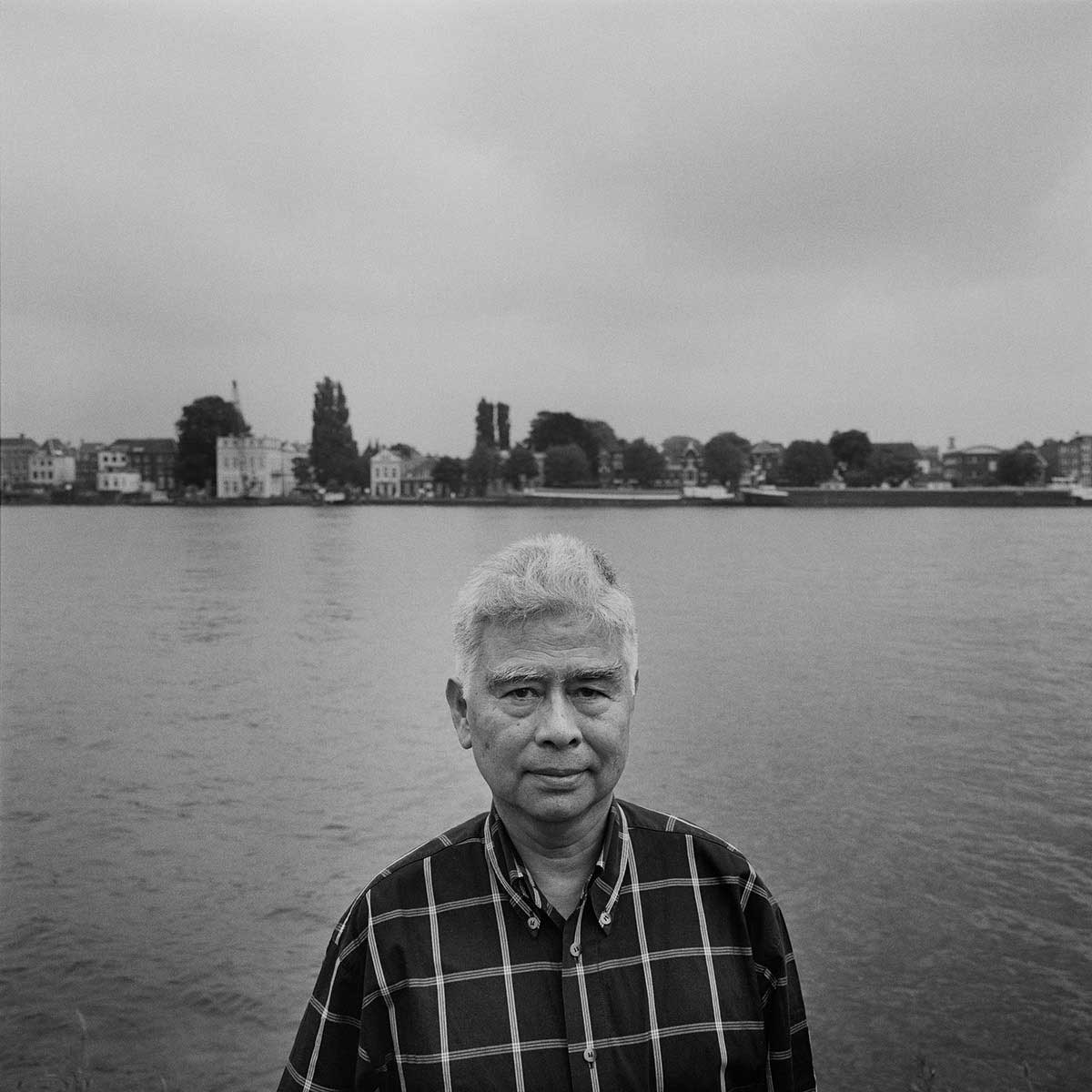

As a result of the decolonisation, most Dutch and Indo-Europeans chose Dutch nationality and “repatriated” to the Netherlands, where they had never been before. Many mothers of children with Japanese fathers married during this period, in most cases men who had suffered from forced labour as POWs at military sites such as the Thai-Burma Railway, and the coal mines and shipyards in Japan. Maltreatment, undernourishment, and no medical supplies during such internments led to the death of many, with the survivors suffering life-long trauma from such sub-human ordeals. Japanese offspring had to face the trauma of their stepfathers in their childhoods, because their Japanese features would often trigger painful memories. These children were isolated in their families and the community.

Even after resettlement from Indonesia to the Netherlands, the Japanese origins of these children would often remain a family secret. Many children of Japanese descent grew up in communities which harboured hostile sentiments towards Japan, a foreign power that took away their way of living and ended the status of the Netherlands East Indies as their homeland. Today, more than 70 years after the end of WWII, many children are still searching for their biological fathers in Japan to fill an important missing element of their identities, and many are still suffering the adverse effects of traumatic childhoods. They take pride in their Japanese roots and they yearn for the land of their fathers as they struggle to solve the puzzle of their origins.

* Estimate by Japanese Consul in Jakarta, 9 April 1969, Asahi Newspaper ** Estimate by a Japanese member of House of Councillors, 30 July 1952, Yomiuri Newspaper

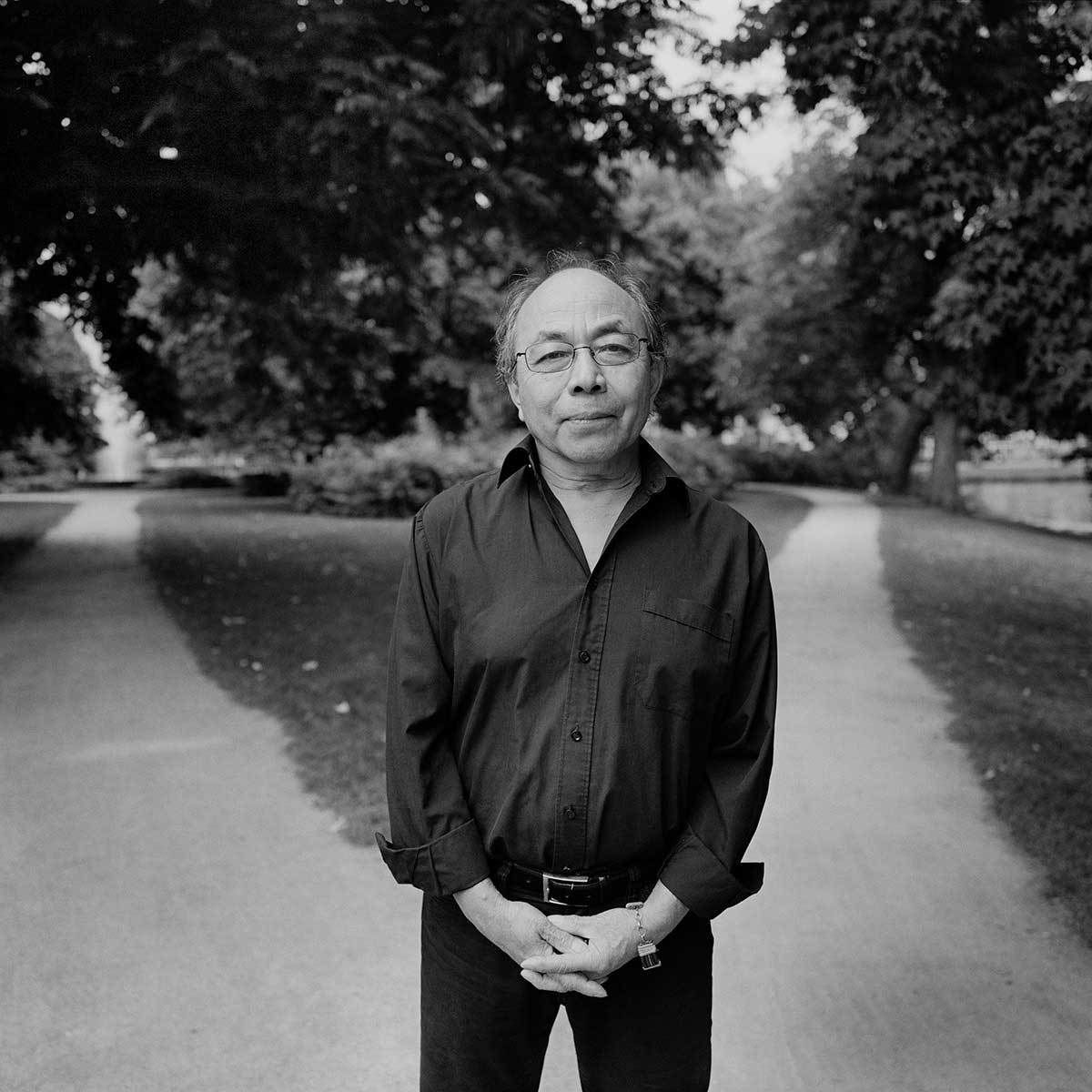

About Miyuki Okuyama

Miyuki Okuyama (b. 1973, Japan) is a photographer and photobook artist living in the Netherlands. Based on her unique perspective as an expatriate Japanese, her photographic works often deal with her own identity and roots, interacting with the others’ in her new environment. Her works have been exhibited internationally and her photobook “Dear Japanese: children of war” won Cortona On The Move Photobook Review & Award in 2016, and it was published in Italy following year. [Official Website]