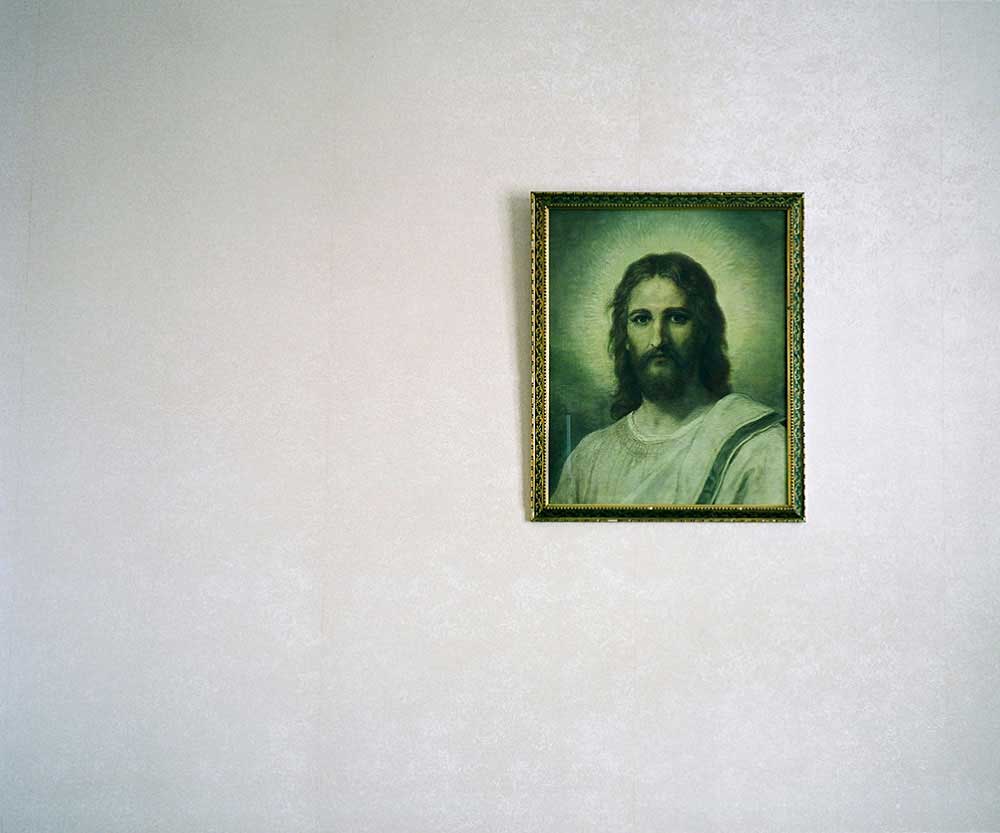

Andrew Jackson’s imagery evokes the concept of the social animal that Proust worked on in his novel In Search of Lost Time. His photographs try to reeducate viewers to make them value old memories and appreciate the nostalgia of our roots and families. It works as a wake-up call to bring back our forgotten stories. Like with the rhythmical blend of African-pop music of Vampire Weekend, our brain starts digging up our past to realize there is nothing better than a family affair.

Andrew Jackson’s approach to migration in From a Small Island, the first part of a trilogy ongoing project, brings a warm and human vision to an issue that has been always described in a cold way through numbers. It’s also quite personal. His work brings dignity and respect, memories are valued and he shows a specific reality and transforms it into a global vision of belonging, and feeling like home. It’s just so beautiful and poetic! I had the opportunity to get Andrew’s thoughts about his work. I asked him how he chooses the participants and the manners he gets them involved in this series, his working process: “From a Small Island was always an attempt to honor not only the legacy of my parents but also that entire generation of Caribbeans who crossed the sea and answered the call from the ‘Motherland’ to rebuild a Britain broken by war. So, in the first instance, I photographed my parents. As the work expanded though, I wanted to explore how my parent’s stories of ‘home’, and the notions of Jamaica they created, had shaped my identity – especially as I was born in England and had no real-world experience of Jamaica”. This is a constant feat in Andrew’s statements, from the single to the collective, from someone’s experience to a group’s experience, from personal relations to a wider human connection. He continues: “The people who participated in the work, while I was in Jamaica, came from a snowballing of interactions. I would meet one person, who in turn, introduced me to another and in turn, they would introduce me to yet another. As you alluded to in your question, immigration is usually described in the UK as a problem. Stats and figures are often used to represent people and I wanted to produce a work which humanized them within my images”. Andrew also supports his humanistic approach to migration quoting a History expert, “as the art historian Professor Eddie Chambers has written “British life has had the disastrous effect of immigrants not being routinely regarded as sensitive human beings, but being instead cast as vexatious problems. Jackson’s work restores humanity to people from whom this critical characteristic has been routinely withheld or withdrawn. And in restoring humanity, a thousand stories of life can be, and are, told.”

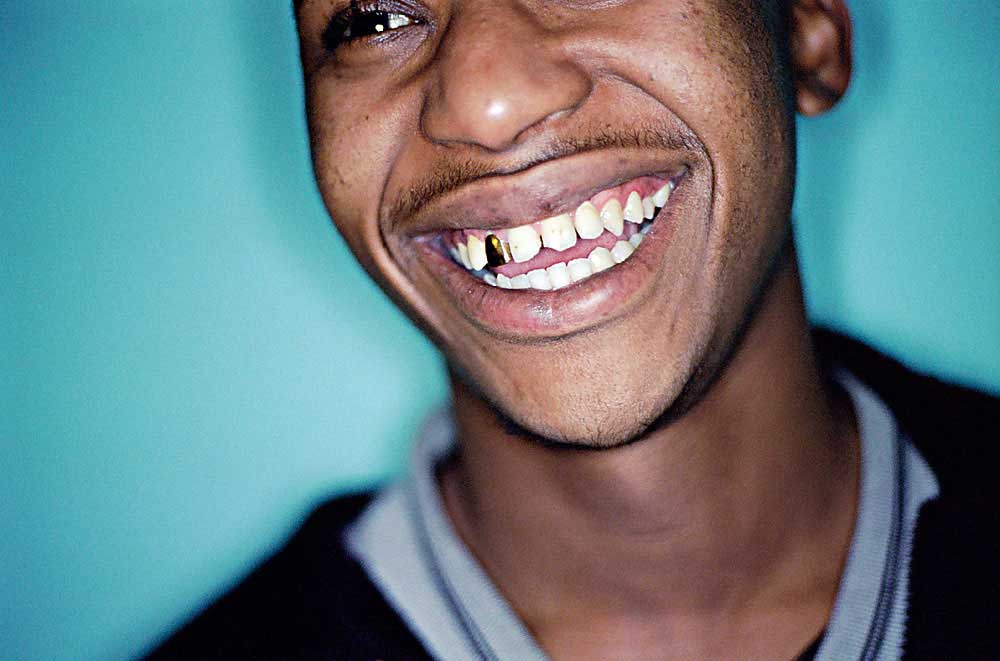

In previous statements, Andrew has said the sense of blackness is multi-angle, curious about this depiction, I’ve asked him to go a bit deeper to define this view of the black lives matter movement and how it shows in his photography. He reflected upon this topic this way: “Blackness is not a monolithic block of experiences, as not every Black person shares the same ideology, cultural or other forms of belief systems. So my perceptions of the Black Lives Matter movement shouldn’t be seen as a catch-all of the Black experience on this topic – they are just my own. II cannot speak for every Black person. But, for me, it has been a reflection, by so many, that Black people can no longer wait for change to happen – they have to make change happen for themselves. I think this represents itself within my work within the humanized depictions of Black people. If we consider that the vast majority of photographs of Black people, taken since the first photograph in 1826, housed in art collections, museums or printed in the media since then, have mainly been taken by white photographers – who have no lived experience of being Black. The fact that I, as a Black man, is photographing other Black people in ways which I see that we exist is still, even in 2020, a revolutionary act”. Andrew’s words are again personal, sincere, and he is also quite conscious of the situation.

It seems Andrew understands the photography’s expression as a way to connect to others. He has also been involved in donations to different causes. I’ve asked him about his role and involvement in ReFramed and CreateSpace, and also what positive aspects have these relations with other creators brought to him as an artist. Andrew explained to me these connections, its origins, motivations, and reasons: “Systems of supremacy, which one could describe as structural racism, are prevalent within all sections of society. Photography is no different. Myself, and three other professionals in the industry, from racialized communities, started up ReFramed as a way of initially exploring how Covid-19 has disproportionality affected our communities in the UK. We have been able to create opportunities, for other artists from our communities, to make work in response to the pandemic. It feels good to be able to create these opportunities for artists who are traditionally excluded from such awards”.

Social housing, working-class women, or youth chances, his topics claim for social justice. His portrait is realistic and at the same time full of life, focusing on atmosphere and space. I wondered how Andrew get to these focuses and he told me: “I choose to focus on the experiences which have shaped my life. I was born into a working-class experience and I have lived, in the past, in social housing. I like to think that I share the same lived experiences of the people I photograph and whilst, I am not visible within the images, that I am present within the narrative. Especially so as their experience has been mine too. Maybe for that reason, I like to think that I photograph people within very humane ways because it is almost a self-portrait of my own life”. Should we take photos of what we know or shouldn’t we? Well, according to his words, Andrews’s answer would probably be to start with your experience and then try to broaden its interest to a global audience. He definitely does that.

Jamaica, UK, Canada, Andrew seems to be always on the road. I wondered where he has found more inspiration to create and develop his projects. Andrew confessed: “It is always easier to find photographs in spaces that are new and not familiar to you. Jamaica has proven itself to be the most intriguing space, currently. But it is a harder place to work than the UK or Canada. The heat is obviously is a factor but also people are more reluctant to be photographed by someone who they don’t know. Which is totally understandable. But now that I have been there a few times and familiarity is setting in it is becoming harder”.

It’s always a necessary question to know how current creators relate to social media and their views about them. Andrew answered me: “My use of social networks has declined over the years but I still see Twitter as the most useful platform for engagement. Facebook seems quite antiquated now. Instagram, well, whilst I understand the need for it and also that picture editors and curators often use it, I’m not very prolific on there. It feels too restrictive for me but it also creates a level of pressure for you to keep posting visual content which is problematic for me as I only feel comfortable sharing work once it has been resolved. Sharing work during the process becomes, for me at least, counter-productive. With Twitter, I get presented with information – on one stream – that would take me hours to source otherwise. I learn something new from Twitter, and strangely feel part of a photo-community, in ways, that I don’t feel on other social platforms. So, on Twitter, I have actually made and become part of new and diverse networks”.

And that was my conversation with this master of photography, Andrew Jackson is a voice to be reckoned with, he has transformed his personal work into a global narrative with magnetic and absolute beauty, a human vision toward social justice. [Official Website]

Seigar

Seigar is a passionate travel, street, social-documentary, conceptual, and pop visual artist based in Tenerife, Spain. He feels obsessed with the pop culture that he shows in his works. He has explored photography, video art, writing, and collage. He writes for some media. His main inspirations are traveling and people. His aim as an artist is to tell tales with his camera, creating a continuous storyline from his trips and encounters. He is a philologist and works as a secondary school teacher. He is a self-taught visual artist, though he has done a two years course in advanced photography and one in cinema and television. His most ambitious projects so far are his Plastic People and Tales of a City. He has participated in several international exhibitions, festivals, and cultural events. His works have been featured in numerous publications worldwide. His last interests are documenting identity and spreading the message of the Latin phrase: Carpe Diem. Recently, he received the Rafael Ramos García International Photography Award. He shares art and culture in his blog: Pop Sonality.