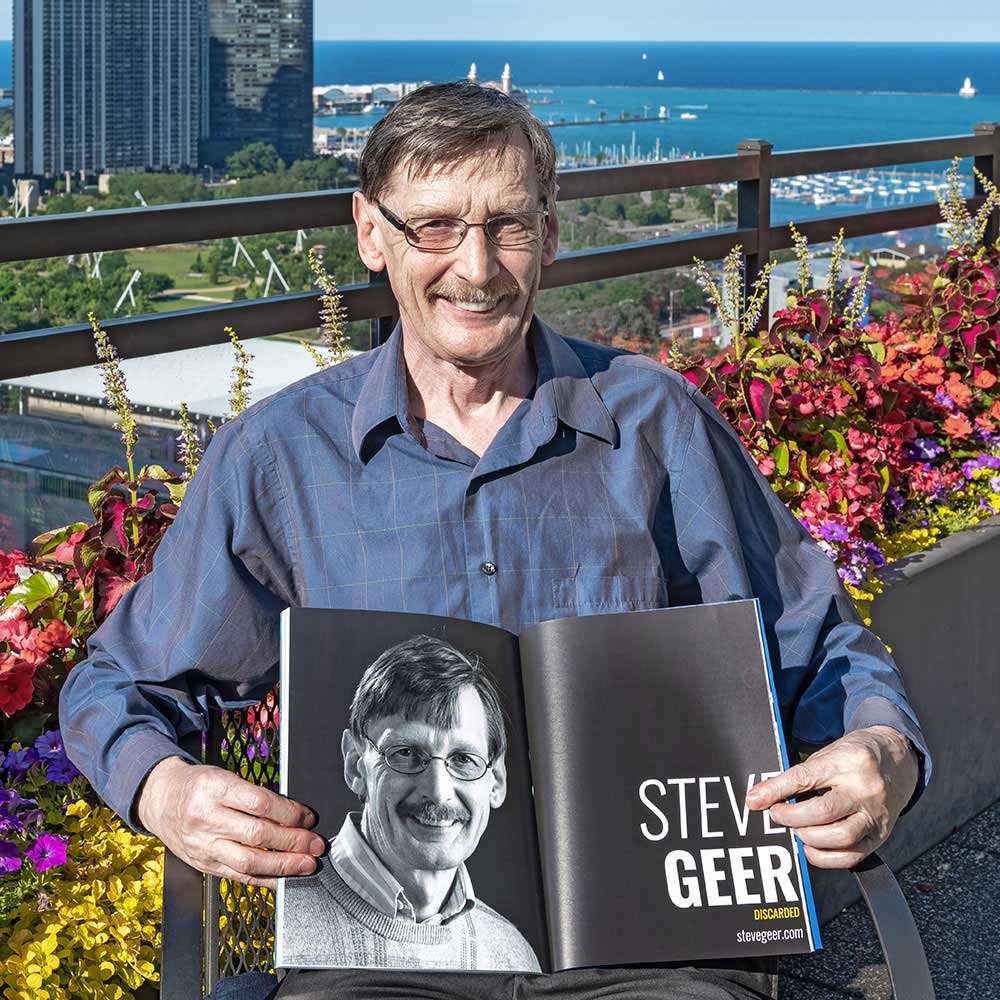

Steve grew up in England. Photography and natural science were the passions of his youth.

After studying physics at Liverpool University, he worked as an experimental physicist in Geneva, Switzerland before moving to the U.S. to teach physics at Harvard University. Photography had taken a back seat but then came the digital revolution and Steve began selling his photographs as stock images. By this time, he had moved to Chicago. After a few years of stock photography, Steve became interested in producing images that provided a greater outlet for his imagination. [Print Version] [Digital Version][Official Website]

How did you get interested in photography?

Philosopher René Descartes is remembered for the dictum “I think, therefore I am.” Photography is the visual part of my thinking.

In my early teens I was given my first camera, a Kodak Instamatic – an all-plastic point-and-shoot box. Although primitive by todays point-and-shoot standards, it was good enough to get me hooked. I saved my pocket money and bought a “real” camera built from metal with a “real” glass lens. It was a Russian rangefinder, a Zorki with a massive light leak that produced a vertical band down the center of each frame. My interest was strong enough to survive the Zorki. I saved once again until I had enough to buy a Minolta.

What inspired you take your “Discarded” project?

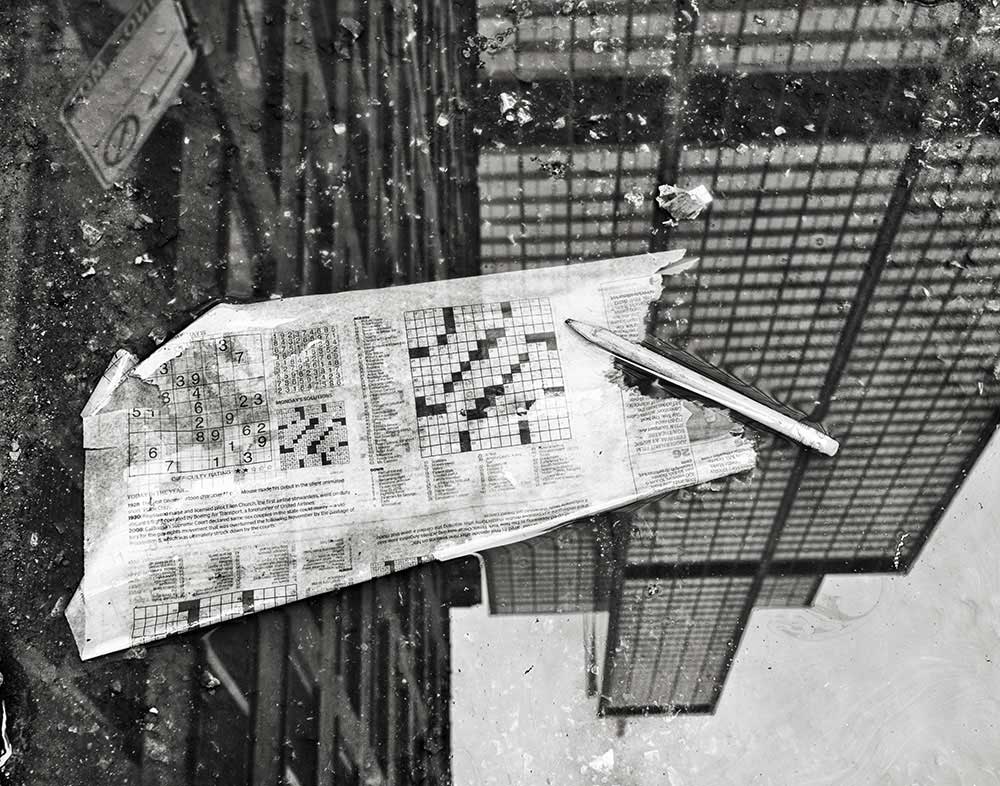

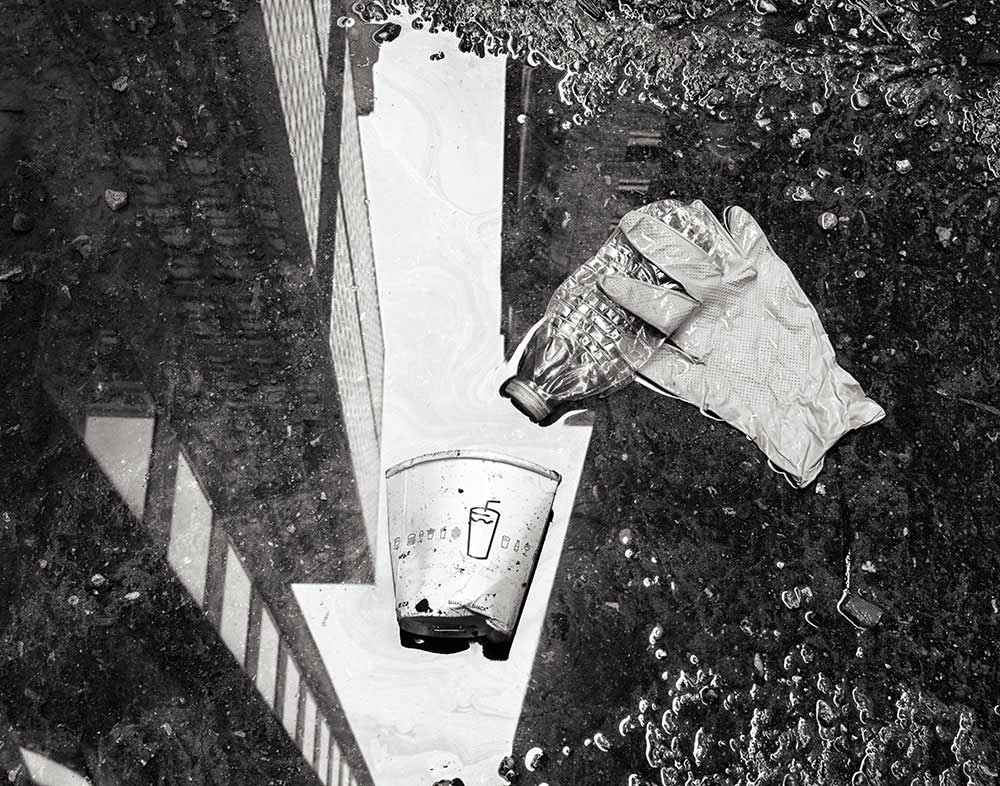

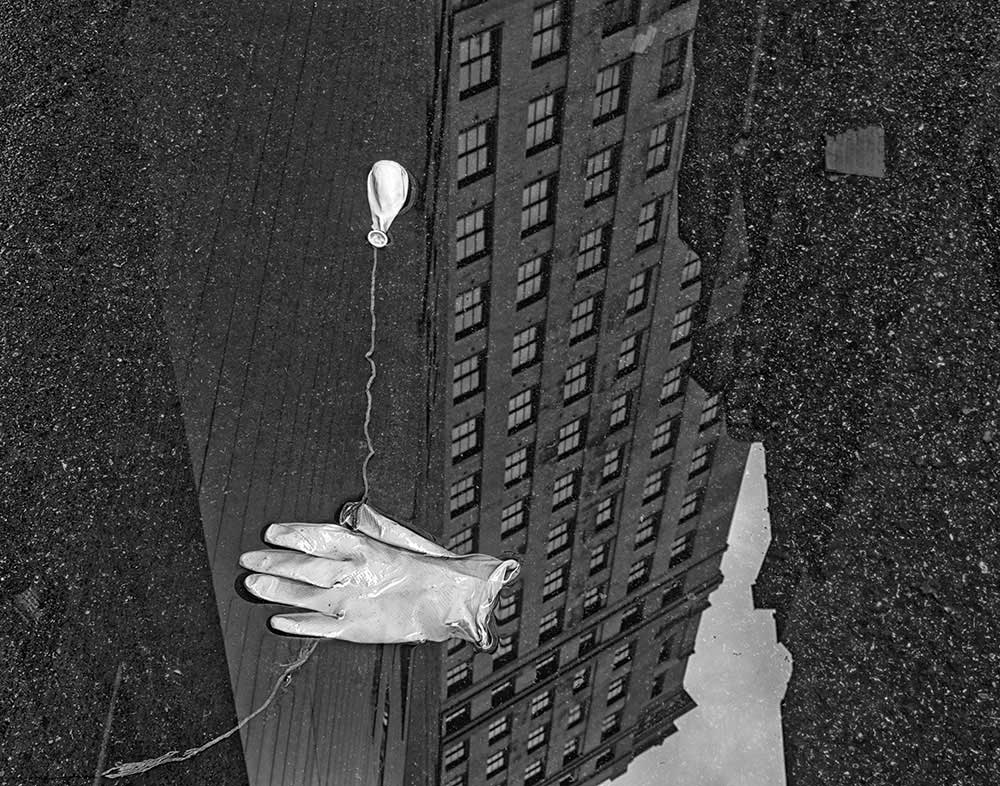

I think there are many sources of inspiration that lead to any particular series of photographs. In a previous project – “Chicago through the Looking Glass” – which was also published online in Dodho – I had been photographing architectural reflections in puddles, many of which were in the same service alleys that I used for “Discarded.” I knew there were discarded objects in these alleys, and I had seen and admired still-life photographs of rotting fruit and flowers. Somehow these things merged together in my imagination and I began placing found discarded objects in nearby puddles, using the reflections to provide a context for the objects. Pleased with the initial results, I soon arrived at the idea of arranging the objects to tell a story based on their usage. Since many discarded things are made of plastic, the ongoing societal debate about discarded plastics, and the damage they do to the environment, also came to mind as I developed the project.

What first drew you to this project?

My personal projects tend to start with an initial idea which then develops and changes as I begin to create images. I can try to rationalize why a project develops in a particular way but in reality, I think the process is organic with success breeding success. I see what works, what I like, and pick up new ideas as I go along. Thus, I don’t really get “drawn” to a project … instead I get caught up in the process and the results.

What has been the hardest part of this project?

Once I had figured out what I wanted to do, the project just required patience and persistence – the warp and weft of any photography project. In a previous project I got used to people staring at me as I stood in puddles with a tripod-mounted camera pointing downwards. I’m also used to returning to a location several times to get the shot I want, waiting sometimes weeks for access to the right puddles at the right time. I carried a plastic bag with me so that I could collect together the found objects that I would need to create my arrangements.

We are talking about the postproduction process. How do you get the final result?

In the digital darkroom, when converting from color to black and white, there’s lots of freedom in choosing how to map colors to tones. I have created a photoshop action to get to a good starting point, but then spend extra time with each image fine tuning the conversion to get the result I want. Once I’m happy with this, I make large prints of the images. Looking at real prints is important because it informs the final tweaks to the postproduction process.

How would you define your general style photography?

Since I live in a city, the bulk of my photography is, in the broadest sense, street photography. However, it’s not “straight” street photography. People might be motion-blurred, objects might be arranged, reflections in puddles might be flipped vertically. Labels used by others to describe my projects have included “abstract architectural photography” and “conceptual photography.”

Could you please tell us anything about your technique and creating process?

Perhaps the most important ingredient in the process of creation is the use of one’s imagination. I believe that if we want our images to provoke the imaginations of others then it helps to inject a little of our own imagination into the image making. I like to experiment so at the beginning of one of my city-based project I’ll try different things to see what works. Once I know what I’m doing, I lock-in and systematically explore every location that is accessible and that might work. That at least has been true for my recent projects.

In your opinion, what makes a good black & white photograph?

“Good” is a very subjective thing. Some images make me smile inside. Those are good images. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously refused to define what makes pornography but said “I know it when I see it.” This can also be said of good images, the ones that make you smile inside.

How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph?

Preparation is important. My projects, which take from several months to a couple of years, typically require some planning and exploration as I search for the right locations. For “Discarded” I searched in Chicago service alleys for several months, looking for discarded objects and for puddles with good reflections. After arranging and photographing the objects, sometimes I would get better ideas or find better objects or better puddles, so many of the final photographs are retakes.

What do you think makes a memorable project?

To make a lasting impression, I think that a project and its imagery must provoke our imaginations and get us thinking.

How do you know you got the shot you wanted?

I get an adrenaline rush when everything falls into place in the viewfinder.

Your idea of the perfect composition?

I don’t know if there’s a perfect composition, but there are strong compositions – the ones that pull us into an image, into its imagination space. A strong composition is like a structurally sound skeleton. It provides a framework within which the viewer can explore.

What future plans do you have? What projects would you like to accomplish?

I have just formed a small group of photographers and poets to exchange ideas and inspire work … a sort of conversation between the two art forms. It’s off to a good start so I’m excited. In the near term, I have a solo exhibition in October at the Cliff Dwellers Club in Chicago, an invited four-photographer exhibition in November at Morpho Gallery in Chicago, and a featured exhibition in February at Perspective Gallery in Evanston, Illinois.

Finally, one last question. What opinion do you have of our print edition?

I think it has a distinctive design. I really like the cover. The full-page portraits of the featured photographers are unusual and, I think, effective. At the end of the day, what really counts is the content – the work that the magazine presents. In general, I find the content inspiring.