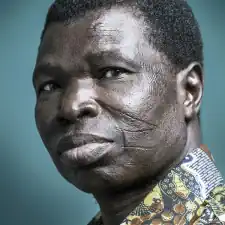

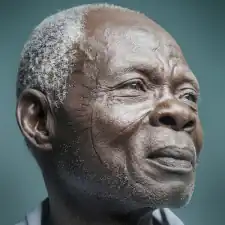

Scarification is the practice of performing a superficial incision in the human skin.

Social scarification has an ancient origin. It is common practice in Africa (especially in West Africa), where it replaced tattoos that show poorly on dark skin. Social scarification is of particular significance, as a ritual of passage to adulthood, or belonging to a small group. It is done with cutting tools such as sharp pieces of stone, glass, knives.

Scarification is a permanent body decoration. The skin is perforated and incised. The wound forming a pattern while healing. In traditional societies, these indelible marks have multiple functions:

• determine the belonging to a supernatural element or social status,

• meet local aesthetic criteria,

• identify members of the same ethnic group.

• We could add the terms “social identity card” to describe this practice. “Ethnic scars are forms of culture and art that African peoples have developed. In almost all sixty ethnic groups in Burkina Faso, we find this cultural value which appears as an identity card, but also as a work of art with its meanings and aesthetic values.” (Sissao, ethnic scarification, CNRS) Few modern citizens appreciated this artistic freehand practice. The ignorance related to this unexplored practice and the mystery surrounding it is scary for most people.

“The mastery of a technical gesture, and what it produces, draws admiration and aesthetic valuing from any observer ignorant of the rules governing its creation. Ignorance usually increases its intensity. Bwaba women (Burkina Faso) carefully

maintained the mystery surrounding their expertise regarding the carving on the skin of complex graphic compositions. Knowing how to carve an image into the flesh of a living body, knowing how to compose and then treat it for its proper healing to guarantee the outcome, have the courage to inflict painful wounds and to face the risks of infection were some of their skills, both technical and moral. These women all enjoyed high esteem and some of them had a reputation that extended far beyond their village. It is only when these skills had been demonstrated that their fame settled, bringing with it the recognition of the uniqueness of their work. Some scarificatrices were then considered like authors having their own particular style, which could be described as such.” (Coquet, 2013, CNRS) This practice is disappearing due to the pressure of religious and state authorities, urban practices and the introduction of clothing in tribes. In many villages, only the older people wear scarifications.

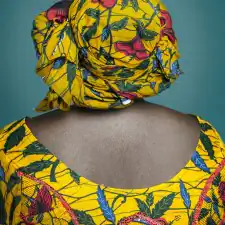

This series of portraits lead us to question the link between past and present, and self-image depending on a given environment. Opinions (sometimes conflicting) of our witnesses illustrate the complexity of African identity today in a contemporary Africa torn between its past and its future. During my research, all I found were pictures from the beginning of the century, taken by ethnologists, and only a few contemporary images. I also had trouble finding people to photograph because of their rarity. This “last generation” of people bearing the imprint of the past on their faces, went from being the norm and having a high social value to being somewhat “excluded”. These last scarified are the last witnesses of an Africa of a bygone era.

About Joana Choumali

Joana Choumali, born 1974 in Abidjan Côte d’Ivoire, is an ivorian freelance photographer based in Abidjan. She studied Graphic Arts at Art’Com in Casablanca (Morocco) and worked as an Art Director for McCann-Erickson, Abidjan before embarking on her photography career. [Official Website]