When I started as a photographer, my knowledge of the photographic landscape was rather limited in terms of the history of photography and the movements within it. It only really extended to what I saw and read in the amateur magazines I began reading.

I had never heard the term Pictorialism, although I most likely would have seen some of the work of its practitioners in those pages. I saw myself as an Impressionist, and would use colour film and many and various Cokin filters, and multiple exposures to fragment and blur reality. Later that year I started experimenting with this technique, that I used at whiles for the next twenty years, until they stopped making the film. I did not investigate other film and drew a line under this period of my work. These early pictures did, however, give me a love of colour which was one of the cornerstones, for the surrealism I was destined to start the following year.

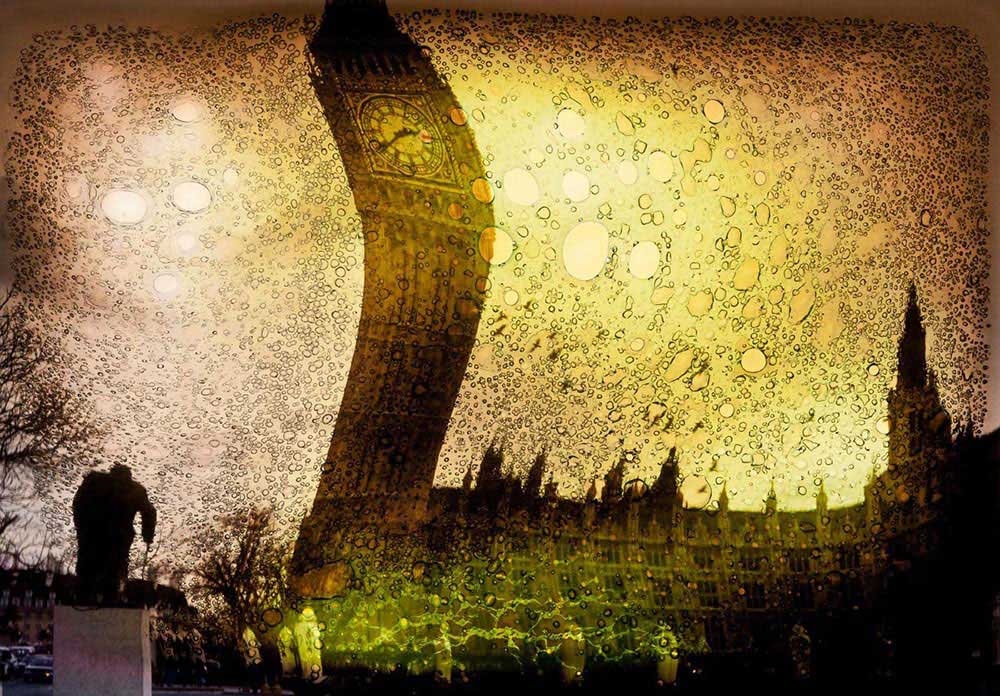

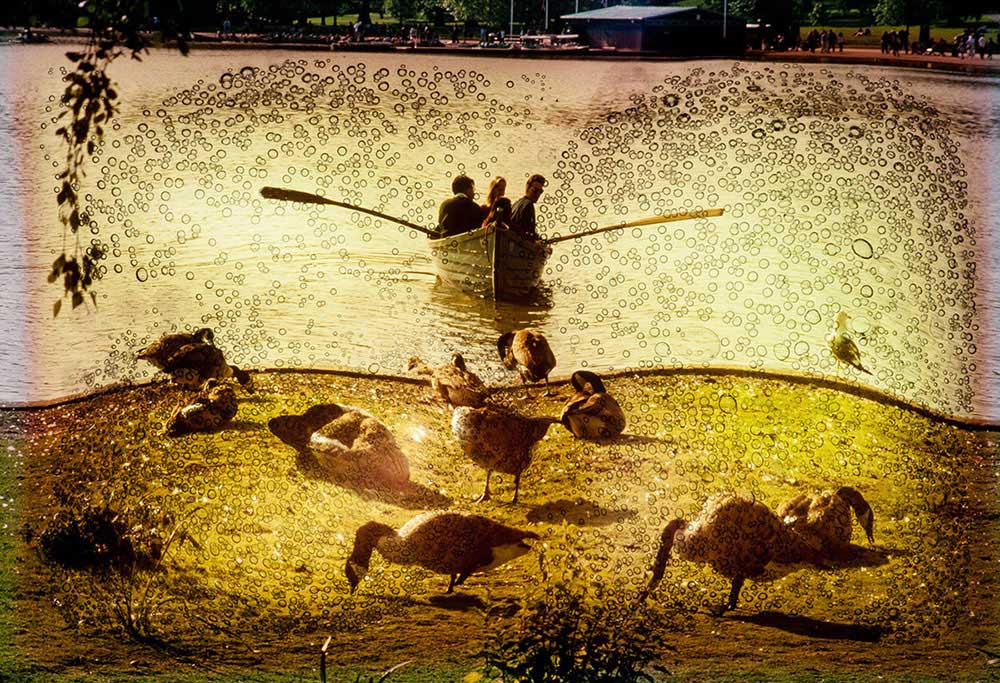

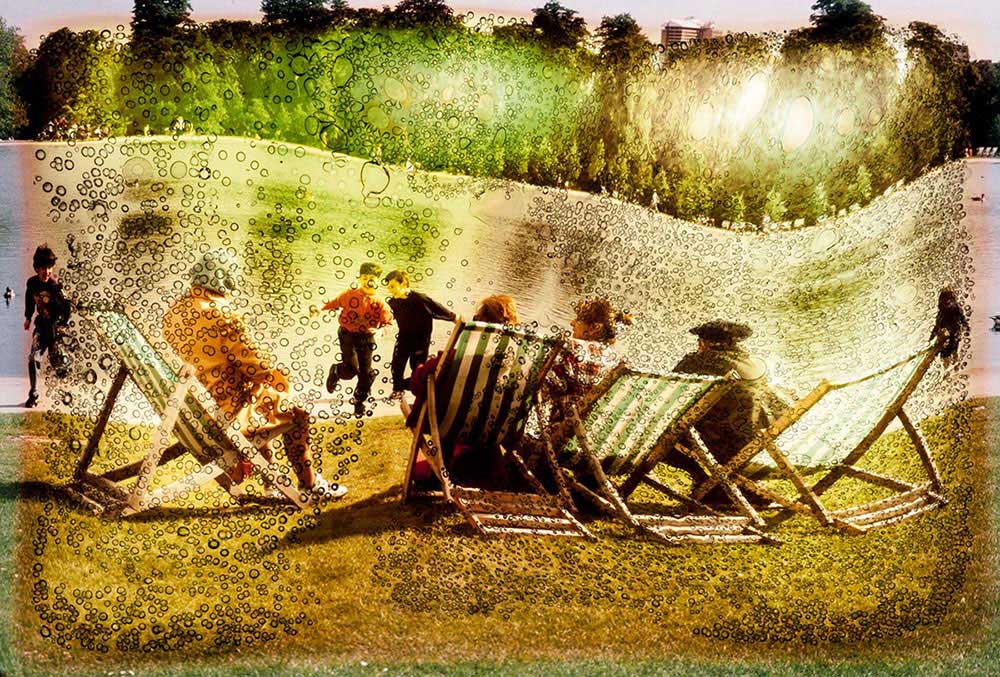

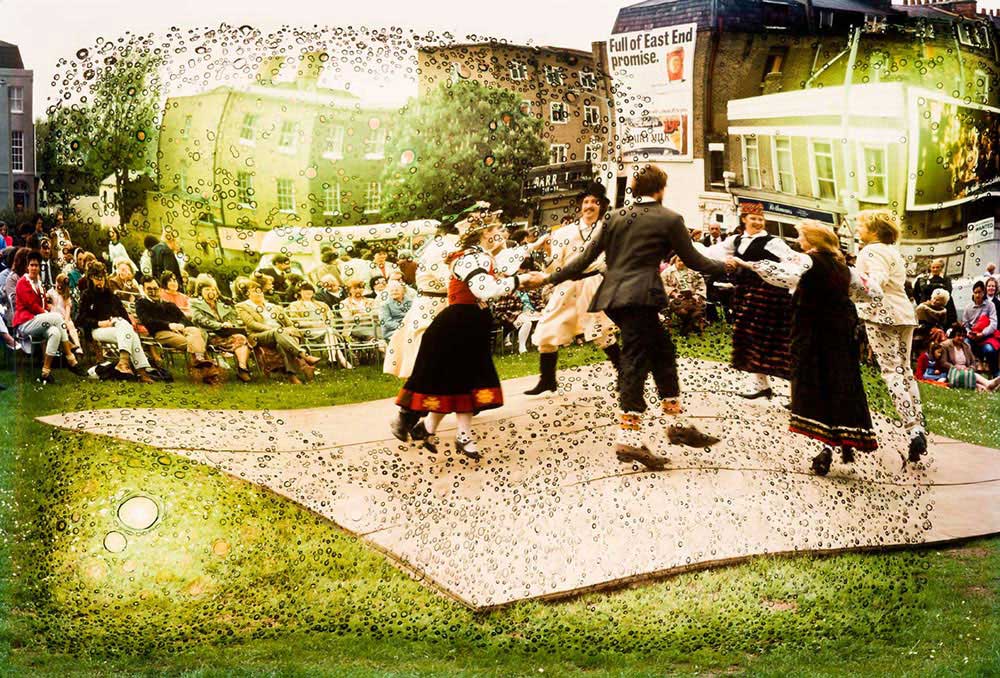

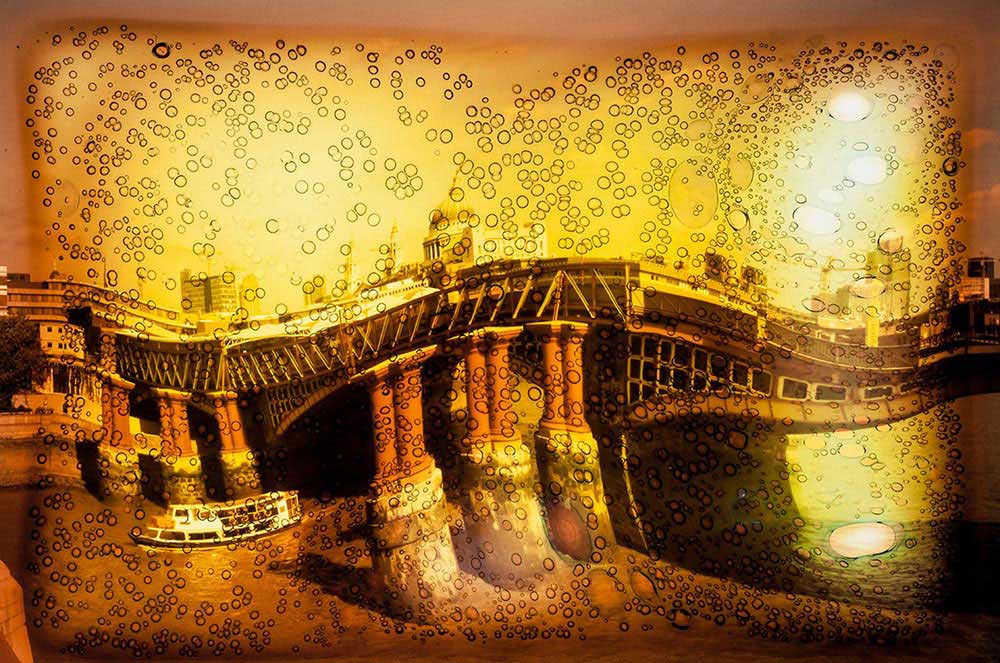

This jewel-like work evokes a haunting dreamlike version of reality. Neither literal nor abstract but somewhere in between, it conjures up a poignant visceral feeling rather than engages the intellect. It is wistfully reminiscent of, perhaps, a child’s eye view of the world as seen through a distorted lens with its texture of bubbles, buckling and warping. It brings back the memory of marbles we had as children and would hold up to our eye, or maybe it is an Alice in Wonderland psychedelic dreamscape.

The technique was designed to complement the low-rise London of ancient monuments where I first began using it before I took it further afield. I photographed ships on the Thames, the British at play on a Sunday afternoon, children at the beach during their summer holidays and quaint villages. After all these years, I recently sat down and I tried to come up with a name for the technique. I had never tried to characterise it before. I had always called them by “bubbles” or my “bubble technique”. Knowing what I know now, I thought them more akin to the Pictorialism of over a hundred years ago than anything else. Because of its uniqueness, its etherealness and the way it’s application could magically transform mundanities into fantasy, I almost called it “Magical Pictorialism” but in the end I went for Neo Pictorialism. When I did a google search, to my surprise, it turned out that the term was already in use and I had been indulging in Neo Pictorialism all those years without realising.

The year I became serious about photography, I looked at all the amateur magazines I was reading and thought, I could not compete with the greats of reportage photography and I needed to go down a less trodden path and my first love was saturated colour photography. This coincided with my move from Southall, where I grew up, which is on the outskirts of London, to closer to the centre of the city. I began taking pictures of the tourist spots, which were as new to me as they were to the tourists, and people at leisure in the parks, especially Hyde Park where I often seemed to end up. I was also using many coloured and multiple image filters to try to get an impressionistic view of the city.

My Neo Pictorialism began when I started experimenting with altering the film emulsion. I tried different film stocks and different ways of applying the technique until I came up with an optimum combination. The bubbles, the distortion and the colour shifts appeared all at the same time. I had some control as to where on the frame to apply it but not much. What I liked about it was that it was like alchemy and could turn an ordinary picture into gold but conversely it could totally destroy a good one. I had to work on the originals and many would go in the bin because they disintegrated or they just curled up. I also could not do too many at once because of the noxious fumes the process created.

What I most liked about it was its complete randomness. It could make a virtue of a grey day or simply trash a great picture and I could not predict the outcome. It gives an illustrative or painterly feel and has a lot in common with Pictorialism, which was a photographic movement that reached its height in the early years of the 20th century. They tried to emulate the painting and etching of the time by using sepia toning, heavy darkroom manipulation techniques, exotic printing processes and even etching their prints with fine needles. Alfred Stieglitz and Alvin Langdon Coburn were among its main practitioners. At the time I had never heard of them nor seen their work but when I discovered them, I could see we had a lot in common.

The very next year I did an about face and started practicing what is largely surrealism, which requires quite the opposite talent, that is, concrete precision. It is what I am better known for and many publications have used my style and I have a monograph published of my work.

I rarely used this style for commercial work but employed it on my walks around London and sometimes on my road trips around the UK. I have pictures of the white cliffs of the south coast, bathers on the beaches of Devon and Cornwall, farmers and sheep in the Yorkshire Dales, narrow gauge railways in Wales and so on. I would often end up on the coast in order to see the sea at least once a year. I would drive and stop when I saw something interesting. I did not have to wait for the right light because the technique would possibly ruin the frame anyway. I called them my “holiday snaps” and over the years I would process them as the mood took me and stick them in my files. After nearly thirty years I thought I would haul them out into the light and reassess them. They were always brittle and fragile and just blowing them with compressed air to clean them, as photo labs used to do, could blow a hole in them. I found some of my favourites were damaged with burst bubbles after being squeezed in files all these years and I had to digitally restore some of them.

Alva Bernadine

Alva Bernadine makes photographs and films. By using themes such as surrealism, sexuality and violence, Bernadine touches various overlapping topics and strategies. Several reoccurring subject matters can be recognised, such as mirrors, shadows, optical effects and representations of the female form. The work is filled with invented surreal scenarios, witty events, troubling scenes from movies that were never made and almost hallucinatory images that invoke narrative, prompting you to imagine what came before or what is about to happen. They are not only about desire but the problems that go with it. Bernadine was born in Grenada, West Indies and grew up on the outskirts of London. He won the Vogue/Sotheby’s Cecil Beaton Award as a young photographer and has since worked for many prestigious magazines and became Erotic Photographer of the Year for his first book, Bernadinism: How to Dominate Men and Subjugate Women.