The Stillness Aesthetic is better known as “Still Life.” In art, whether it’s painting or photography, this pursuit has been about clarity as it relates to light, in the rendition of the inanimate, as well as the animate.

This has been the practice, not only in the visual arts, but, in photography as well. It takes us back to that day in 1838, when, after inventing the Daguerreotype photographic process, Louis Daguerre recorded his first photograph of shoe shiner servicing a customer at a street corner in Paris.

Photography’s operating premise has been to freeze the action. To make still. To make still the live subject to record it on the negative. Thus, the stillness aesthetic was born. It has been about freezing the moment in time, whether it’s a landscape, people, or a street scene. The stilling of a scene or stopping the action was done by a faster shutter speed. The default photographic aesthetic has been about light, angle, and composition.

Photography at first, was unequivocally, to thwart misrepresentation, impression, and uncertainty. Any molecule of ambiguity was the antithesis to the idea of certainty. The concept of ambiguity was a fearful proposition, it being the anathema to what photography stood for. For much of photography’s 19th and early 20th century’s journey, it had been about generating a photographic record, as the aesthetic factor was relegated to the back seat, to the concept of recording. Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner may have been the earliest photographers to record a cataclysmic historic event, the American Civil War. It was the most accurate depiction of the event. And, right up to the Second World War, governmental record keeping included Dorothea Lange’s depression and dust bowl photographs, and Ansel Adams large format photographs for the Department of Interior. Even at the Judicial courts, photography’s straight forward use was to influence the verdicts. The advent of photographic aesthetic was relatively late.

The closest photography ever came to represent impressions was when intrepid photo experimenters of the early 19th century, used pin-hole cameras to record scenes. The captured scenes were almost as if they were painted in brown or drawn with charcoal. These photographs were not the deliberate result of a photographer’s pursuit of aesthetic by camera control — rather, the results were influenced by very rudimentary and inadequate mechanisms that were the beginnings of what we call today the camera. The early cameras allowed the photographer only one control, to guess accurately the amount of time needed for the light to create the image on the emulsion coated surface. Ironically, this one control resulted in some of most aesthetically charged images. George Davison (1855-1930), was one such photographer, who captured that iconic and monumental photograph: “The Onion Field,” through his pinhole camera, sometime in last quarter of the 19th century.

The concept of still life is an oxymoron, as is the camera. Even with all that technology at our finger tips, we cannot aesthetically skirt any of those iconic images taken with pin-hole cameras in the mid 19th century. This leads me to this simple maxim that we presumptuously ignore: it’s never the equipment! It’s in our observation, sensibility in sensing. This sensing leads to creation. Painting with a camera? This becomes a challenge when photography is still being held hostage to its early rudimentary capacity, in total ignorance of its labyrinthine capacity.

The argument: The rousing question. How can life ever be still? The concept of “still life” is a paradox! Do we exist with clarity in complete transparency? Is stillness our fundamental condition? And, even in the aesthetic context, is clarity, only found in stillness, and is this the only way to perceive our condition? Life, if we know anything of it, is never still, and is never lived in clarity. It unfolds in vague

impressions, fragments, half truths, and uncertainty. Life is motion, it’s a blur. Motion is the fundamental operating principle that governs life, and this paradoxically and intriguingly envelops life in uncertainty and ambiguity — this is our collective condition.

Speaking of our collective condition, it is no where more evident than in the theater of war. Who can ever forget the iconic and impressionistic moments of desperate motion of soldiers in the water during the Normandy landing on June 6th 1944 as photographed by Robert Capa . His photographs put us in that water, their desperation and anxiety is contagious. Another chilling photograph by Capa is from the Spanish Civil War, when we are put right before the execution of a soldier. Accidental, incidental? I am not sure, but we sure can guess Capa’s intention. I could, without any doubt, claim that Capa had stumbled on to something with those handful photographs – that life unfolds in movement, it’s the author of our condition, in our bliss, or in our abject bestiality.

The proposal: The pathology of our condition: which is motion, does not preclude agitation, anxiety, flashes and raging impulses, even when we are still, seated, apparently in stasis. Motion is the very manifestation of existence, denied by our illusions of stillness. Isn’t emotion movement while being still? Dorothea Lange and Richard Avedon proved that life is motion even in stasis, beyond any doubt. Life conducts itself at life speed, within our 55 millimeters view. Our movement, especially in an urban setting, is never one smooth linear narrative, it’s fragmented, discursive and ambiguous. In this photo essay I seek, first, our condition, which I perceive and sense as ambiguity in various textures. Second, I seek to illustrate this condition as it is.

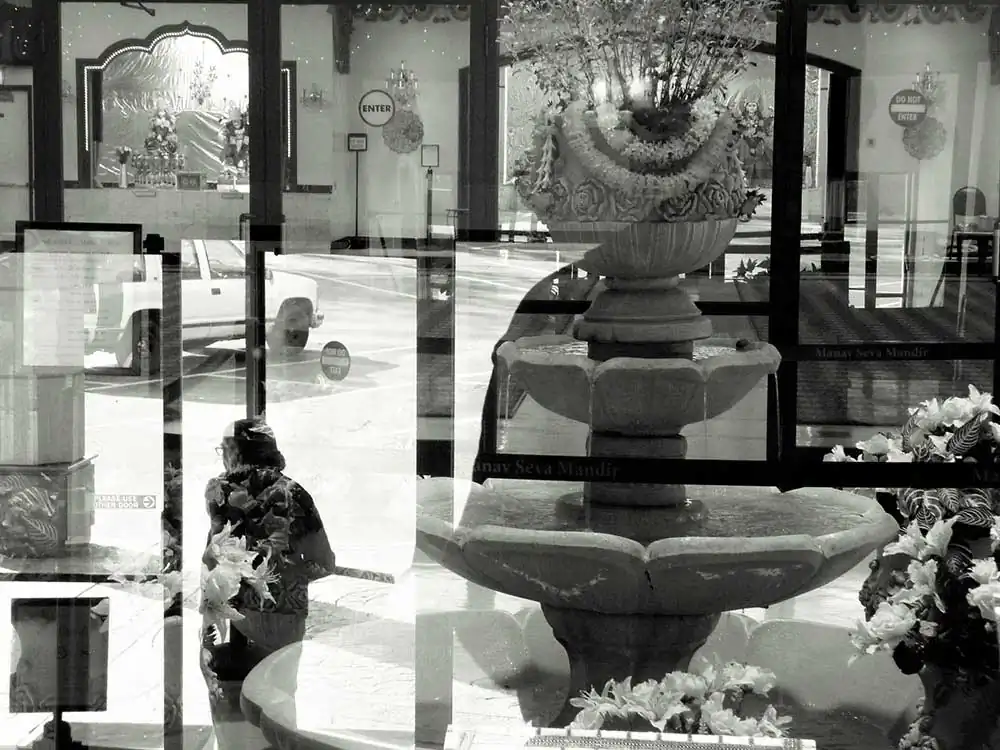

This brings me to my main objective, to present the new a aesthetic, intrinsic to our ambiguity. Like the Japanese pottery master, Hon’ami Koetsu, I seek imperfection. I seek the asymmetry in our existence, its fleeting and fragile beauty. I seek imperfection and textures caused by our condition: a perpetual transience within ourselves and our environment – the same way the practitioners of Zen seek out the worshipful textures of transience and age in nature. In similitude, if we are able to sense these textures in our kinetic condition, we would derive not only an understanding of our condition, but experience something insightful and profound: beauty that is never obvious. A palimpsest of beauty, inherent in our transient daily transactions that we can only sense. Imagine sensing people shopping, people in cafes, or walking on the street not as discrete activities but as strokes of a painting, as elements in larger phenomenon – the composites of existence, if you will. I set out seven years ago to capture our urban condition as it is: as impressions and abstracts, in reflections and aberrations, in refraction and fractions, and, in distractions and vibrations. Every time I shot a picture hoping to get two distinct human activities, I did not see the third and the forth that came onto the photograph… a perfect metaphor?

Since ambiguity constitutes life – the aesthetics of ambiguity is not only my postulation, but, my proposal for divergence, from the convention of the still life aesthetic that had held photography hostage for more than a century. It’s an earnest attempt to show life in impressions, by evocation and provocation, just like any painter or writer worth his salt would. I am attempting to make visible that which is uncertain! Stillness is an illusion, an oxymoron relative to life, while movement is ambiguity, both have a way of balancing our sensual and visual equilibrium!

Finally, my photography reveals a practice that is not much in practice: capturing impressions and abstraction. Photographic art, like a diamond, has many facets, some facets are still unexplored, and my goal is to find that aesthetic facet that best represents our contemporary

urban condition. My photography is postulation itself, as well as the proposition that life is not still, therefore, we must develop the capacity to sense and enjoy this new emotional and intellectual theater of transience: our urban canyons, without always having to travel to the Grand Canyons of the world. I call this the majesty of the mundane, now available as “The Aesthetics of Ambiguity” in the theaters of your senses! [Copyright, Raju Peddada, May 2017.]

About Raju Peddada

Raju Peddada was born in India, and became an American citizen to pursue his passions and ideas in the industrial arts. He is the CEO and Chief Creative Officer of the eponymous brand, PEDDADA that has been in existence since 1999. He holds twenty-two design patents, and is credited with critically acclaimed product launches. He is an artist, with exhibits at professional art galleries and Chicago’s venerable SOFA shows. He also is a free-lance journalist, with over a hundred articles in literary and culture magazines, republished by the Bookforum and the NY Times. He writes on photography extensively, and has previewed and reviewed shows by the legendary photographer, Art Shay. Peddada’s review book on Shay’s exhibit titled “The Curative Literature of Art Shay” at the Loeb Gallery in Paris was praised as the best ever review, for the insights on the works of Shay. He has authored four books and is on the verge of releasing three new books. He also experiments in photography, and has created aesthetic categories he is getting ready to publish. He has been featured in scores of design- culture-social magazines as the “Taste-maker.” Peddada had been featured in a two page article in the Chicago Tribune’s best selling edition for his design inventions. He was also highlighted on CLTV Cable news for his passionate design entrepreneurship.