I have always been interested in how unwitting visual arrangements create structure (composition) and how they affect me.

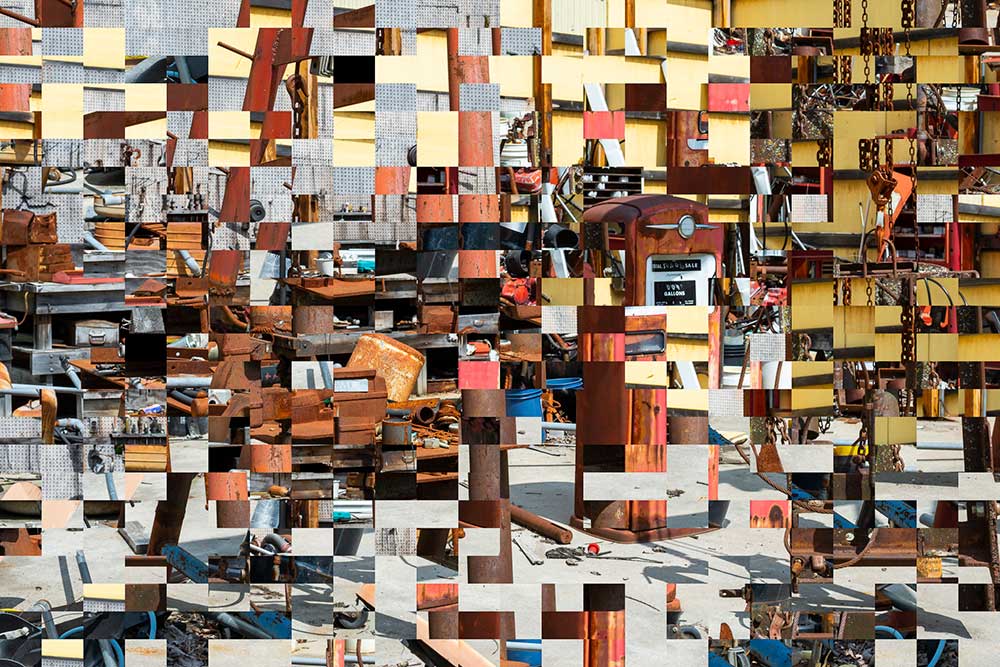

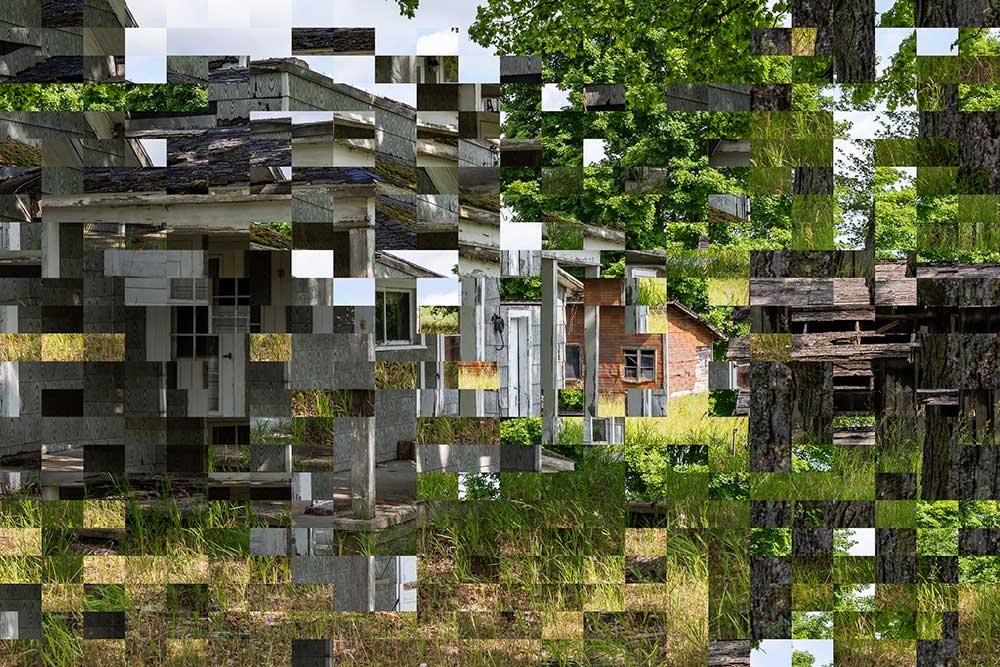

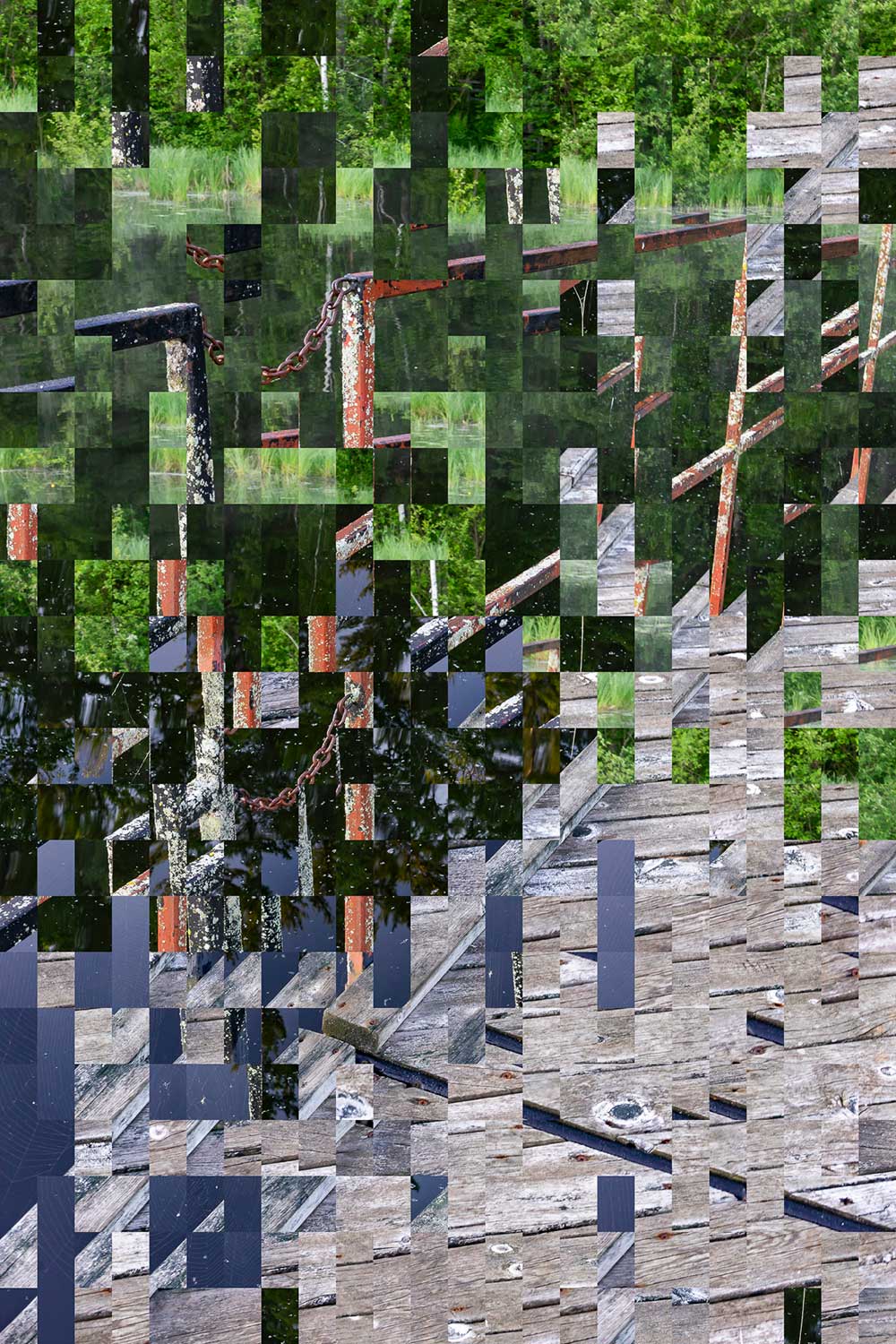

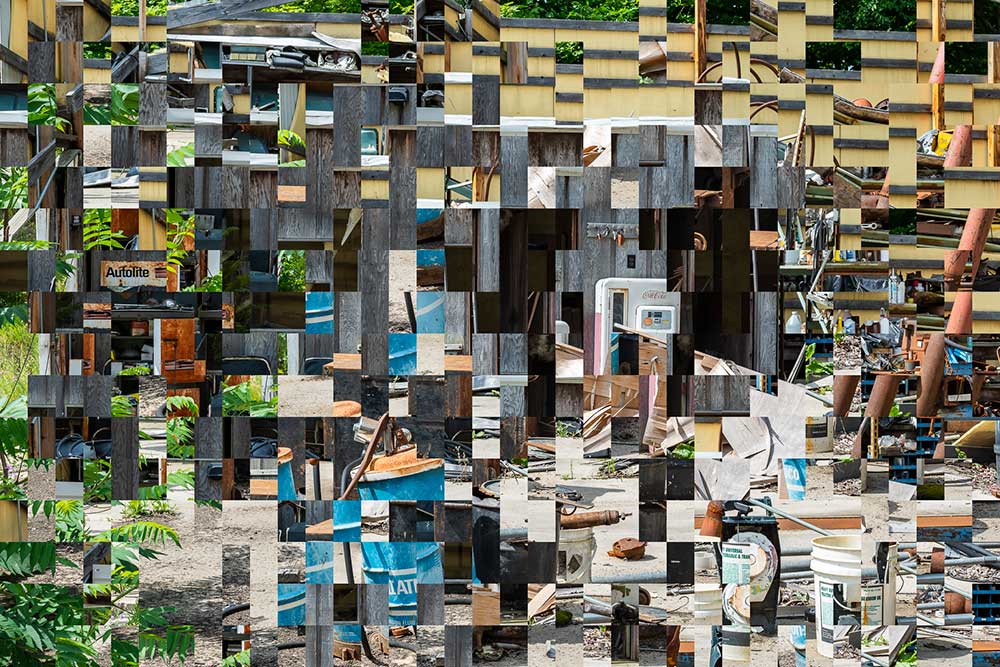

I am curious about traditional, domestic still lives. I am drawn to capture images of arrangements of abandon and deteriorating equipment and buildings and think of these as exterior still lives that signal my concerns of deterioration and loss.

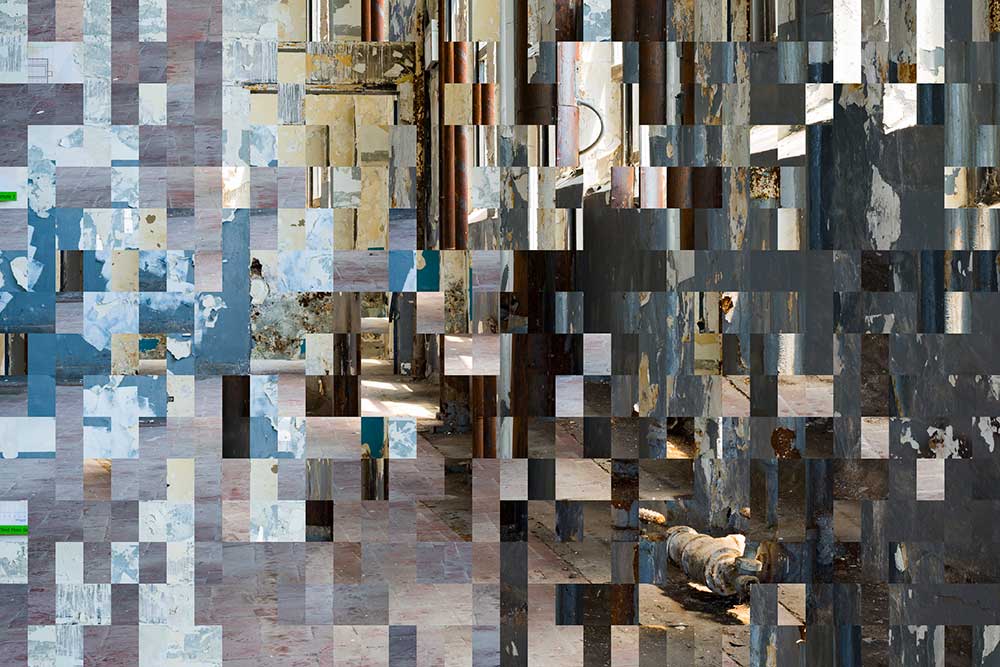

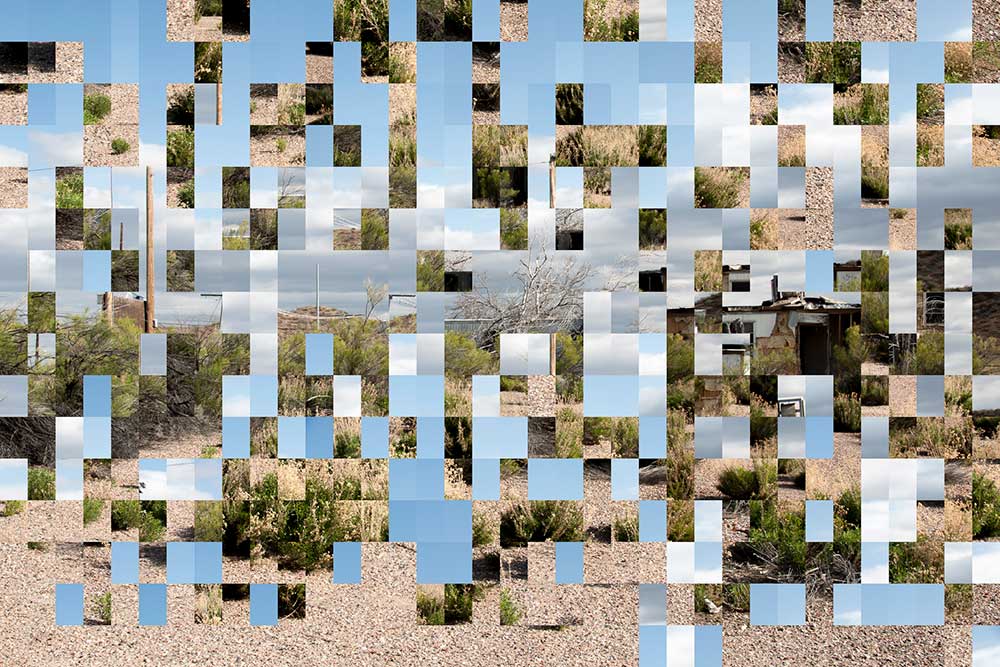

Photographs in this project are reassembled to challenge viewers to consider photographs without the resemblance and the composition that are central to the Modernist conception of photography. As much as resemblance is heralded as reality, photographs are disconnected from the reality that we take them to be. Reassembly produces a self-collage that signals, as collages did a century ago, an expected, disturbing reality and by producing an (oxymoronic) non-representational photograph.

Reassembling photographs takes constituent blocks out of context while each and every piece of the photograph remains visible and each and every piece–and the whole–remains a photograph. Reassembly converts a single photograph with a single frame into hundreds of photographs with as many frames emphasizing the frame over content through repetition. The reassembly of photographs figuratively illustrates that photographs are immediately and forever taken out of context.

Reassembly could be pushed to the level of pixels to create chaos, but small regions of each photographs remain recognizable so that one can identify the deterioration and loss captured in these photographs.

Loss of context of any photograph creates graphical discontinuities at each of its edges that point to precipitous loss after a finite length, time, or life. While the durability of photographs suggests a kind of immortality, the inherent discontinuity of the frame, the rectangular photographs and their reassembled components, and the abandoned and deteriorating objects in these photographs serve as a poignant metaphor for our finite lives. As the original structure is hidden in and by the overall chaotic appearance of the distorted image, this treatment suggests a loss of usefulness and value and perhaps our progression away from a more structured life and toward chaos. Western religions promise an afterlife as structured as life. I believe in a chaotic afterlife. This project helps me, and perhaps viewers, deal with our ultimate concern.

Most people are more likely to use photographs to distract themselves from the deterioration and loss of people, objects, and situations that they hold dear. Reassembling images that remind me of my beneficial experiences challenges me and other viewers to recognize differences between photographs and memories. Memories are fragmented. Memories depend on small sets of marks (represented by the small sets of pieces in the collages that remain in context) for recognition. Resemblance does not offer recognition. Composition is required to select those object that become the subject (the actors) of the photograph. Nevertheless, those parts of the photograph (resemblance and composition) are ineffective without the experiences within the photographer and the subsequent viewers, that is, existing memories. Feelings are also not part of a photograph. Feelings are a response of the viewer to earlier experiences. Photographs do not store feeling nor emotion; memories store emotions created by experiences and the actors that affect us. Photographs are not memories. The resemblance in photographs is an indiscriminate consumer of objects in a scene and is devoid of the emotional content stored in our memories.

I have used reassembly to create images for three related books of images and ideas under the title, Out of Context into Chaos . The books are Deterioration and Loss , Memory and Photographs , and Photographs and Reality . Each of the books contains an essay that runs through the book formatted as quotations–pieces of text taken out of context. Within these books, the idea of out of context extends into the third dimension with small pieces of images appearing in other images and text pages on nearby pages. [Books and prints]

About Michael G. Prais

Michael G. Prais has worked at the intersection of art and technology since 1996. He grew up in suburban Dearborn, Michigan, the home of the Ford Motor Company, during the post–World War II heyday of the auto industry. As a visual person who has always been interested in how things work, he has moved easily between the concrete and the abstract. He enjoys helping others analyze functional explanations and naturally became a teacher helping others to understand and use abstract tools.

As a first career, Michael sought to understand how mathematics works in service of science. He studied chemistry, physics, and mathematics, and earned a doctorate analyzing the distribution of vibrations in mathematical models of the surfaces of crystals. He taught physical chemistry until his background in information and communication technologies drew him to support personal computer technologies for university faculty, students, and staff.

In a second career, Michael sought to understand the dynamics of learning, teaching, and motivation. He applied his insights to supporting university faculty adapting modern information and communication technologies for use in their teaching and productivity. When an art department sought his assistance supporting an Adobe Photoshop lab, he started on a path to understand and engage with photography. Leveraging his mathematical and scientific expertise, he authored Photographic Exposure Calculations and Camera Operation , a definitive book on how cameras operate.

More recently, Michael has examined the mechanics of composition and the workings of photography and, more generally, art. He is fascinated by the interplay of the designed and the organic and examines both human constructions in nature and unexpected, coincidental arrangements of the unwitting human hand. Michael now uses photography to investigate how random acts create structure. [Official Website]