Aysén, Chile, a region of some 103.000 souls (density of population: 1/km2), sits in one of the most remote and undisturbed areas of the world. Its ecosystem is among the most remarkable still in existence.

The area is home to some of the rarest plants and rainforests, many endangered species of animals, pristine rivers with high aquatic biodiversity, and the largest ice fields outside of Greenland and Antarctica. Aysén was the last area of Chilean Patagonia to be developed. Extreme isolation, rough geography, made it extremely difficult to settle.

In 2014, the Chilean government put a stop to an 8-year-long battle of environmentalists against HydroAysén, a megaproject that sought to construct 5 dams and hydroelectric plants on the Baker and Pascua Rivers, in order to support Chile economic growth, its mining industry in the north and the increase in energy consumption.

The dams would have irreversibly altered the ecosystem, flooding good ranching land, ancestral homes, damaging a traditional way of life and unexplored land, unknown even from most Chileans. It would also have required a 1,912-km transmission line demanding a forest clear cut some 1,600 kilometers long and 122 meters wide, roughly the distance from Boston to Savannah.

The campaign to protect Patagonia became the largest environmental struggle in the country’s history, and it opened the door for social movements and changed the political landscape.

I have made one extended trip to the region in 2012, photographing Patagonia’s endangered landscapes, its way of life and the people directly affected by this project. I have been photographing in Chile for more than 10 years now, mostly in the north of Patagonia, in Chiloé.

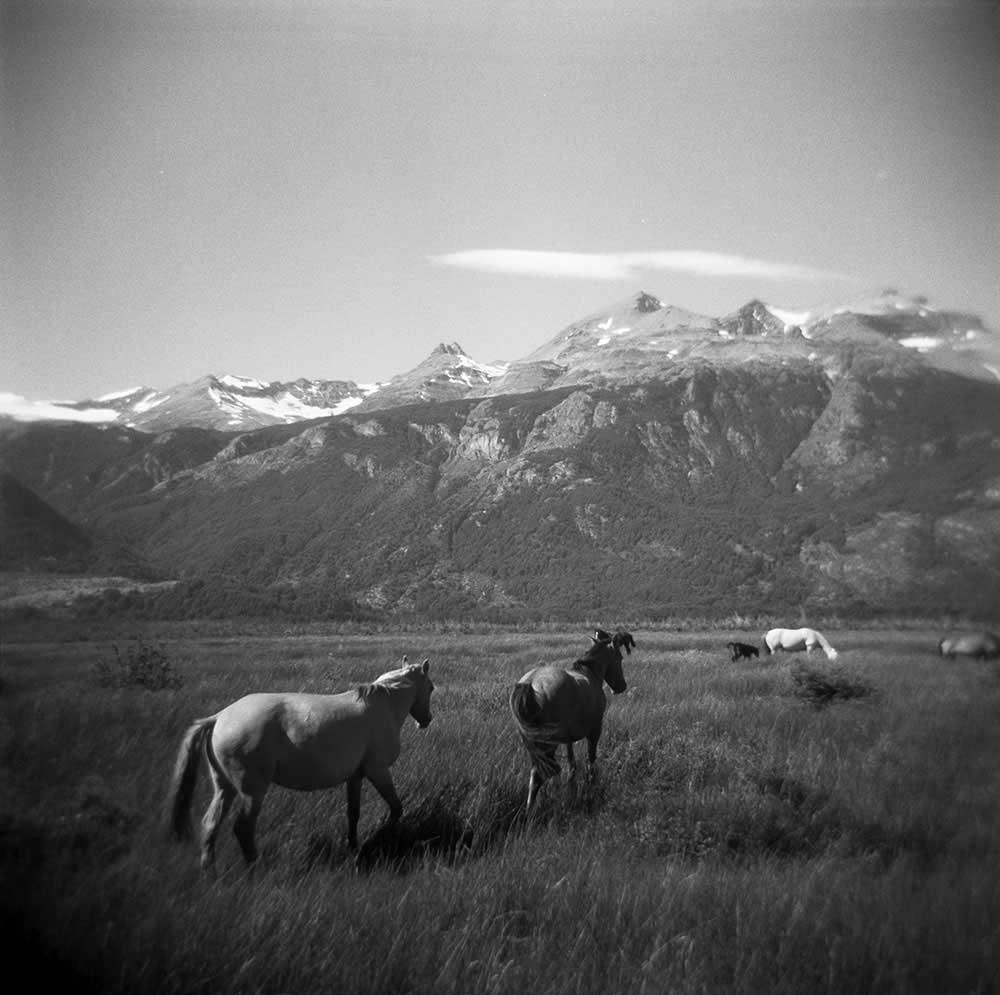

During my trip, I visited communities along the electric line. Life is difficult in this region. The cost of living is higher than in the rest of Chile, due to its isolation. The main road that serves the area, “The Carretera Austral,” is mostly a gravel road. At the end of the road, Villa O’Higgins, closer to the Pascua River, still has the atmosphere and the aura of the pioneers who settled in the region about a century ago. Traveling depends on weather and volcano conditions, changing boat schedules, the difficulty to communicate. Many people don’t have electricity. They can only communicate by radio. Men live alone, their wife and children live in small towns, to allow the children to go to school. They are reunited during the school holidays. This is when I visited them, when families are together in their farm.

The descendants of the settlers who came to explore these lands have developed a tight relationship with nature. It’s a place where they work hard, but also breathe, and live quietly.

One night I was standing on a tiny island in the south of Chile and my friend’s grandfather told me :”When you look at all those stars, how could someone claim there is no God?” For as long as we can recount, traditional and indigenous people have been celebrating our relationship with nature in their songs and stories. These days our society has gradually become disconnected from the natural world, and therefore lost any sense of responsibility towards it. In the process of the so-called world’s development, places sitting at the edges of the world are being destroyed and something is lost forever. Beyond the disastrous environmental consequences, something else is being sacrificed: our connection to our roots, our history and diversity.

It has been a long-standing tradition and motivation for photographers to record what is threatened by demolition or the passage of time. Aysén is a rare and precious place, with a unique culture, a mix of tehuelche roots and pioneer spirit. Lilli says: “There is no land like ours.”

About Brigitte Grignet

Brigitte Grignet is a Belgian photographer focusing in a more personal and emotional type of documentary photography. She studied photography at the International Center of Photography in New York, where she lived for 15 years. She worked with Mary Ellen Mark for 10 years and is represented by L’Agence VU’.

In 2011 she was rewarded with the Aaron Siskind Foundation Grant for the project she worked on for seven years in the south of Chile, “La Cruz del Sur,” where she recorded a way of life slowly disappearing, with its centuries-old social structures and cultural traditions. She received the Prize of the Minister of Culture (Photography Museum in Charleroi, Belgium) in 2017, the Marty Forscher Grant for Emerging Photographer in 2001, and the Fotografiecircuit Vlaanderen from the Photography Museum in Charleroi (Belgium) in 2003. She won the Washington Post Open Call in 2017 for her series about a maritime boarding school in Belgium.

She is a 2016 Magnum Emergency Fund Grantee for her project “Welcome,” that documents the reality of unaccompanied children seeking asylum in Belgium.

She was an artist-in-residence in Francisco Toledo’s CaSa (Oaxaca, Mexico), Isola Comacina (Italy), Atelier de Visu (Marseille, France), and Villa Pérochon (Niort, France).

Brigitte collaborated with Action Against Hunger in Guatemala, Colombia, and Palestine. She tells a story of people and their indomitable will to survive difficult situations and their continual quest to build and live within a life of dignity and grace.

Her work has been published among others in Newsweek, The New Yorker, the Washington Post, Photo District News, Le Monde, FotoVisura, NPR 100 Words on Photography, Libération, El Pais, Days Japan, Lettre Internationale, Private, Granta.

Her images have been widely exhibited internationally and are included a.o. in the collections of the Kyosato Museum of Photography, The Photography Museum in Charleroi, the Portland Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson and the agnes b. collection. In 2015 Yellow Now published her first monograph “Present Perfect.” [Official Website]