Photographing the dead is his job. Niraja, 20 year old, runs one of the photo-studios in the busiest streets of Varanasi, the oldest living city in the world.

Niraja waits for the families during the procession that lead to the crematorium. If he’s lucky enough, he’ll get a few rupees from the clients who want a pictures of their loved ones. The Kashi Manikarnika Ghat is one of the holiest burial grounds alongside the river Ganga in India. According to Hindu mythology the burning of the bodies is the most sacred ritual because it symbolizes both creation and destruction of mankind. It is believed that being burned on the land of Varanasi, provides an immediate liberation from the cycle of births and rebirths. To be cremated along the banks of the Mother Ganga is seen as the highest honor to the people living in the community.

The smoke load with the smells of burned wood and skin is so thick that it penetrates your clothes and the odor stays there for days. The only sound in the air is the chant that echoes between the mud walls accompanying the body in its final journey: “Raam Naam Satya Hai” (the name of Ram is true). The Ghat is open 24 hours a day and more than hundreds of cremation ceremonies take place daily all year round. For the community, death is a form of livelihood. Among the people who live off the death of their neighbors and friends are wood merchants, barbers, Antyeshti (the priests performing rites and prayers), florists and groups of outcasts sifting through the mud searching for personal belongings of the deceased. Among the many jobs, there are also the photographers of death. Their job is to capture the last moments of the departed before they are turned to ashes. Photographing a dead person may seem unconventional and a little disrespectful to the families, but for the photographers of Varanasi, it is just another way to earn a living. The family of the deceased actually encourages pictures to be taken, not only as proof, but also as closure to families unable to make it to the funeral. Since crematoriums do not provide death certificates, the pictures are the only proof to the government to receive any type of inheritance.

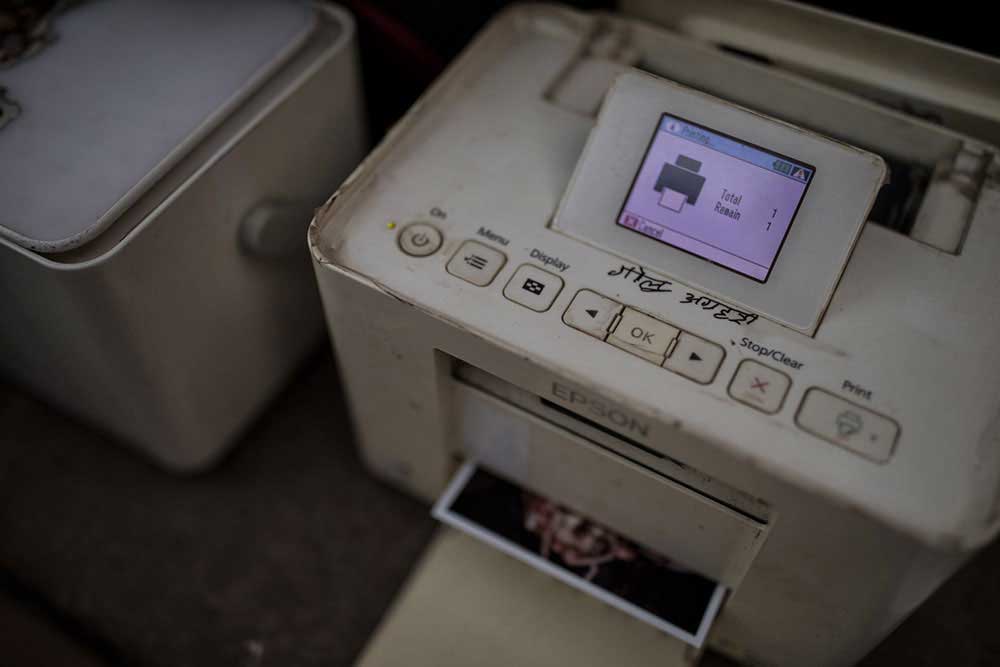

Naraja is one of them for more than five years, a job that has been passed down to him and in his family for generations. He has two cameras, both broken. With one he’s able to get the shots but not to visualize the photos because of the damaged lcd screen. To see the images, then, he needs to transfer the memory card on the other camera that, instead, has a broken lens. Photographing a person on the death bed may seem awkward to most of us, but for the death photographers of Varanasi, it is just another way to earn a livelihood. And if somebody wonders why people would want pictures of the dead body, there are many explanations. Families want them for different needs. For family members who cannot attend and would like to see the final moments and show it to the coming generations. Or to prove that the person is dead for government records and inheritance. At this crematorium, families don’t get death certificates, so the photographs work as a proof. With the date and time printed on the photograph, people use them to claim their share in the deceased’s property.

When Niraja is done with the shooting and the family is satisfied with the photographs, the cremation ceremony can begin. The work of Niraja, however, is not finished yet.

The wood starts to flame and it takes almost three hours for the body to rise up in ashes.

This is the only time Niraja has to run as fast as he can to be able to reach the lab right outside the city, to develop the pictures and come back. Supposing he will miss the family and leave without the pictures there will be no profit for him. This is the only time Niraja has to develop and deliver the pictures. Supposing he will miss the family and leave without the pictures there will be no profit for him. He needs to run as fast as he can to be able to reach the lab right outside the city, to develop the pictures and come back.

“Photography for me is not looking, it’s feeling. If you can’t feel what you’re looking at, then you’re never going to get others to feel anything when they look at your pictures. I love taking pictures, I love this job and I feel honored to do what I do.”

While I observe him, I can feel him struggling to grasp the essence of the shots. His ability to capture images that celebrate the interwoven ideas of life and death with elegance and grace is so inspiring. Two things that, as in no other place, are inseparable. A real honor for those people whose dream is, in their last years, to be brought here and cremated along the banks of the Mother Ganga.

About Mauro De Bettio

Definitely, to grow by himself, without the influence of schools, courses and lessons has slowed down the process of technical knowledge, but because of this he learned his own way of seeing and been formed and shaped by the environment and the people who surrounded him in his long travels/trips.

“Although it is difficult to express, I think that the photograph represents my way of speaking and what I try to do through my language is to capture the sense of what I breathe and touch with my hands. Not only in appearance but also, and especially, in the essence; trying to express nuances and subtleties contained in a single frame. I think that’s part of my personality and my work fully expresses what I am. My story, my soul”. [Official Website]