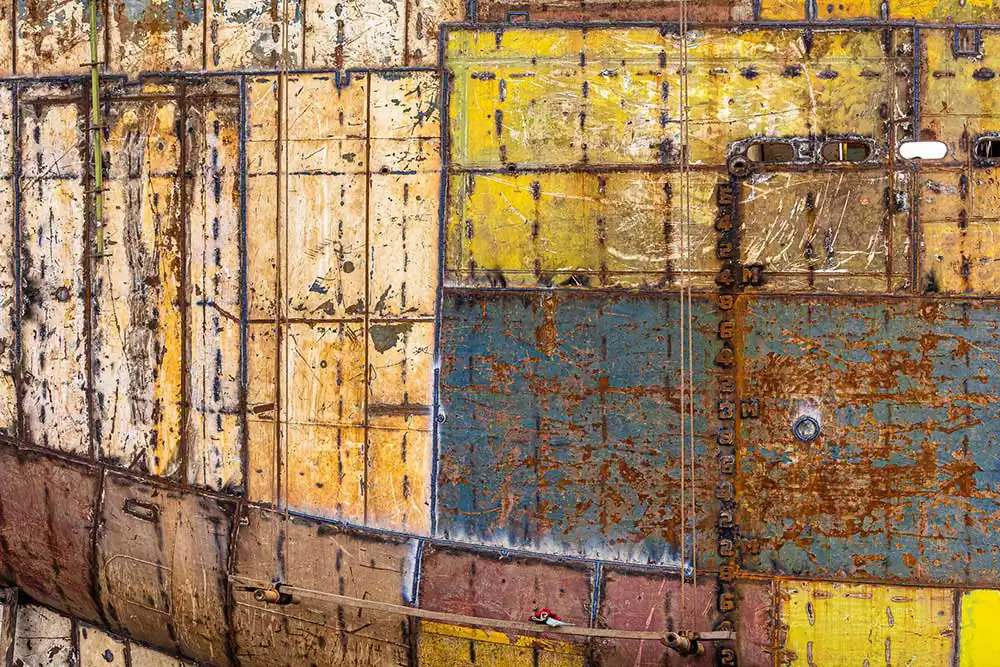

“Do you see all the yellow paint? I have done all of that in the last 2 weeks”; says Tanvir Seakh (25) while holding his yellow painting brush.

The side of the vessel looks impressively yellow, but there is also a lot yellow paint on the ground and on himself covering his hairs and his face. “No problem”, Tanvir says: “with a yellow bit of Octan (car fuel) we are quickly fresh again”.

Tanvir is proud of his work, ignoring the health and safety risks. He is happy to have a job and he feels proud to work on such a gigantic steel construction. Today his job is easy as he is painting the lower part of the vessel, but many days he is hanging on a jute rope on the top of the ship to get it painted. Per month he earns around 10.000 taka, which is about 100 euro.

Tanvir is not the only one, together with him there are approximately 15.000 to 25.000 workers directly employed and probably about 100.000 find indirect income through the approx. 145 Ship Wrecking, and Ship Building companies. In the first three quarters of 2021 there are 582 ships scrapped worldwide and 197 of them (34%) in Bangladesh. Details are not known for 2020 probably due to the pandemic, but in 2019 there were 234 ships dismantled in Bangladesh.

The ship wrecking generates an approximate $1,5 billion dollar annually for the country. The good news is that Bangladesh until recently was only breaking the ships, but recently they also start building new vessels, an industry that generates much more added value than just scrapping alone.

The construction of the vessels is impressive as its mostly done by manual human manpower. Its plain muscle strength that is building these big vessels, some of the as large as 150 meters long and as high as a 20 storied building. You see the workers with nothing more than some basic tools and a welding machine.

Construction of a ship is also a dangerous job, especially because most of them do not work with a safety harnesses or protection equipment. Several of the workers have had accidents, and some of them even loose part of their hand or feet. Workers can be exposed to asbestos, especially in the older ships. There are also concerns for the quality of the paint, some of it might contain lead, arsenic or cadmium.

For Tanvir this is not something that he is thinking about regularly. He waives away any of such concerns, “are you coming?”. Before I can realize, he already climbed up the small steel ladder that swings dangerously because of his steps. He is half way on his way to climb to the top of the ship when he looks back at me. He dangles 15 meters above me, and reach out his hand as if he wants to help me climb the stairs. Well, stairs, some metal pipes connected to some ropes. “The view is great from the top!”, he says before reaching and he is out of my sight.