We all know it, but no one has ever actually been there. Or they were there long ago, maybe when it was a completely different town, for it is said that there are several towns in that place and that they reveal themselves when the veil of their façade is accidentally lifted to reveal a Polish or a Hebrew inscription, in rare instances German or sometimes Russian.

Lviv is a town that not even its residents know, and that is fine, for as soon as you begin to realize who you are you begin to put on an act and lose yourself forever. That is why psychotherapists and travel guides will never be anything more than erudite archaeologists, pathologists studying the cells of a beautiful girl – and that girl might be our soul or the soul of the place where we find ourselves. Lviv is a beautiful girl who does not know she is beautiful, who has other worries than putting on her makeup. She is a girl about whom men in Bohemia sometimes dream but whom they never find, a girl for life, a girl who simply enjoys that she exists.

At the corner of the old square, a fragile old woman joined me, looked at me, touched a button oin my coat, and then bent towards me, quite close, like a small girl wanting a caress. She didn’t know how to begin the conversation, and so she began with the standard Where are you from?, probably because of my shoes, or the button. And I answered exactly according to the rules: Prague, the Czech Republic, for a week now, one more week. The old woman, after some hesitation, pulled an ace from her sleeve, the latest edition of the Ukrainian version of The Watchtower. How to explain it to you, how to explain it all, she murmured to herself. And then a spark appeared in her eyes and she knew, she began to leaf through the magazine until she found a picture with some stylised homunculi, a young Barbie doll, and next to her a woman who looked like an aged movie star and my old woman pointed to the aged fatal woman and then to the Barbie and then again to the fatal granny and whispered to me, All this will be no more, nobody will get old, all will be young, and she looked at me with a winning look and touched my button again. And when I looked into her light blue eyes, I could see that the miracle had already begun.

While the endless queue of the needy in the park in front of the city armoury quietly moves towards the soup pot, he sits down in the nearby shade, places his plastic bowl with today’s ration on the bench, and like every day carefully divides the slice of bread into three parts. One for now and one for tomorrow. And the third for the pigeons. And when one black pigeon flies away with its catch of the day, away from the flock, perhaps it, too, will divide its ration into three parts in the shade of the pissed-on shrubs, and the ants are already queuing up impatiently.

The armoury in the centre of Lviv is guarded by an old soldier. He guards it from pigeons, the homeless and enemy aliens. This is his most difficult task, to hobble over to the stairs and check on foreigners, and if it is an “ally”, to tell him about the sand and the feathers between the stones in the wall, sand and feathers, like a cushion for a stray bullet, like a cushion for this tower that hasn’t held any gunpowder in a long time. The sand and feathers will stop every projectile. But there were no feathers in Afghanistan, and that is why I lost my leg there, but at least when I was on guard duty there, I didn’t have so many visitors and I didn’t have to walk up and down the stairs to the attic, and there was more dust and sand than here.

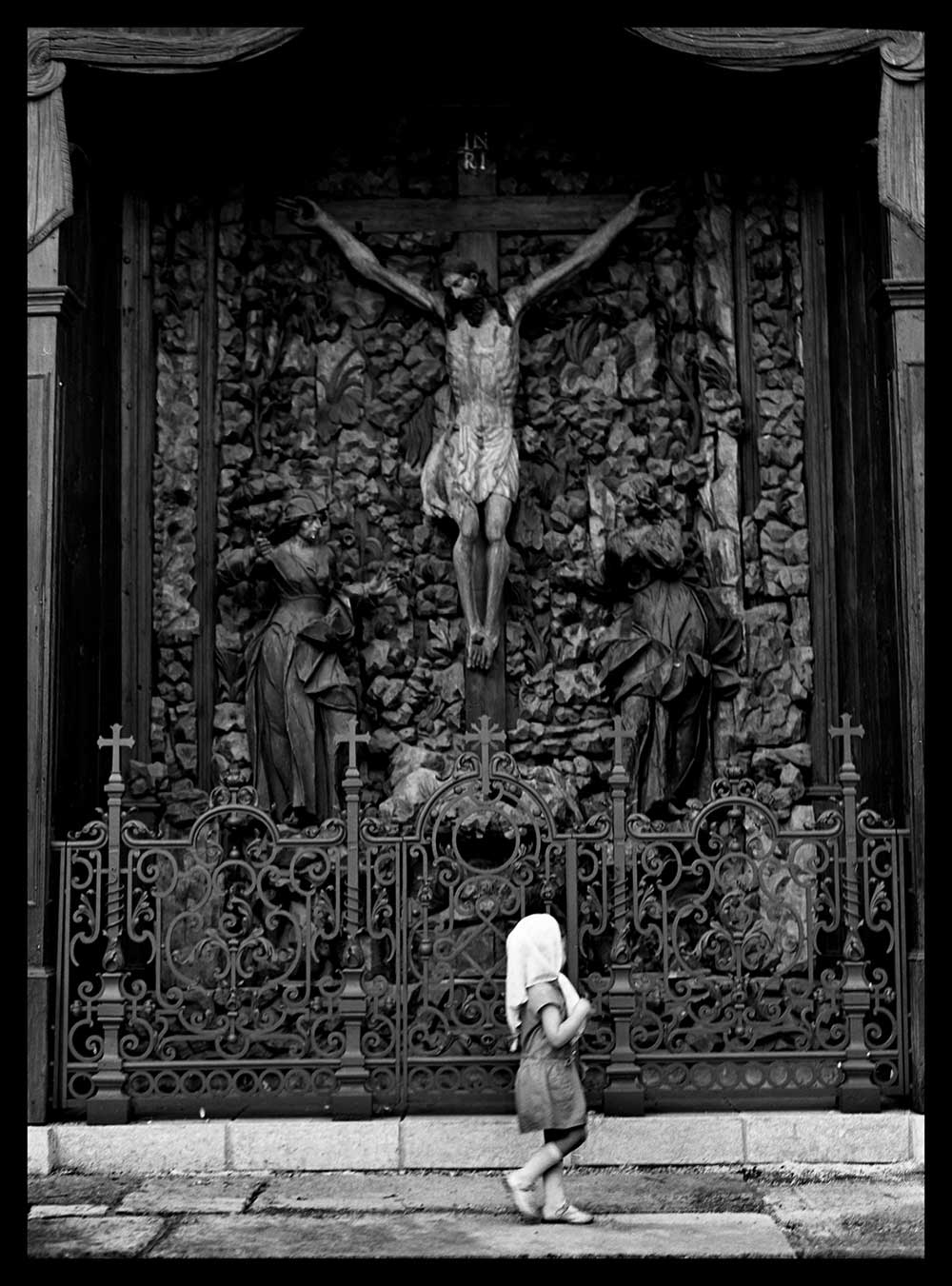

It’s just the two of us in the whole café, Jarko Khomyk, the “Aznavour of Lviv”, who has never heard of Charles Aznavour, because he plays only here and that is enough for him. And I, his audience, tap along on my own keyboard in an accelerated rhythm of images. When he finishes his song, he tells me that it was about Lviv, the song, you know, everything is a little strange here, it rains a lot, and in the rain, in the slowly falling drops of rain, things are happening, a man turns into a church or a church turns into a man or maybe a bird, everything keeps changing here in Lviv, all is in the rain here all the time and you can never know for sure what you are seeing, but that is good since you are always being surprised, amazed, for even if you walk down the same street or pass the same place a hundred times, in this rain you can never know what is there or what will be there next time.

About Igor Malijevský

Czech poet, photographer and writer was born in Prague in 1970. He studied theoretical physics as well as philosophy at Charles University, were he graduated in 1996. Since the mid-1990s he has devoted himself primarily to photography and writing. He has published four books of poetry and two collections of short stories, including Moon Above the Tagus River (2014) which is represented in anthology “Best European Fiction 2018”. He co-established EKG, a well-known monthly literary cabaret in Prague and regularly cooperates with Czech Radio. His BW analog photographs have been exhibited in numerous exhibitions in Europe, USA, China, South Korea and other countries. He published three photobooks including Signs of Lvov (2016), a book of poetic BW images from this Ukrainian town accompanied by texts in Czech, Ukrainian, and English. Recently he is regularly returning to Ukraine to capture its everyday live during the war. [Official Website]