[What would Daguerre say, if he saw what photography had become?Could he have imagined that his invention of tonal realism, had become an ever expanding nebula of creativity and record of our varied conditions – vectored forth by legions of unknown practitioners, that have enabled us to retrieve moments long lost in time and space?! July 14, 2018, 1.45 pm]

“Photographs bear witness to a human choice being exercised in a given situation… it’s is the process of rendering observation self-conscious.”

John Berger, Booker Prize winner for “G.”

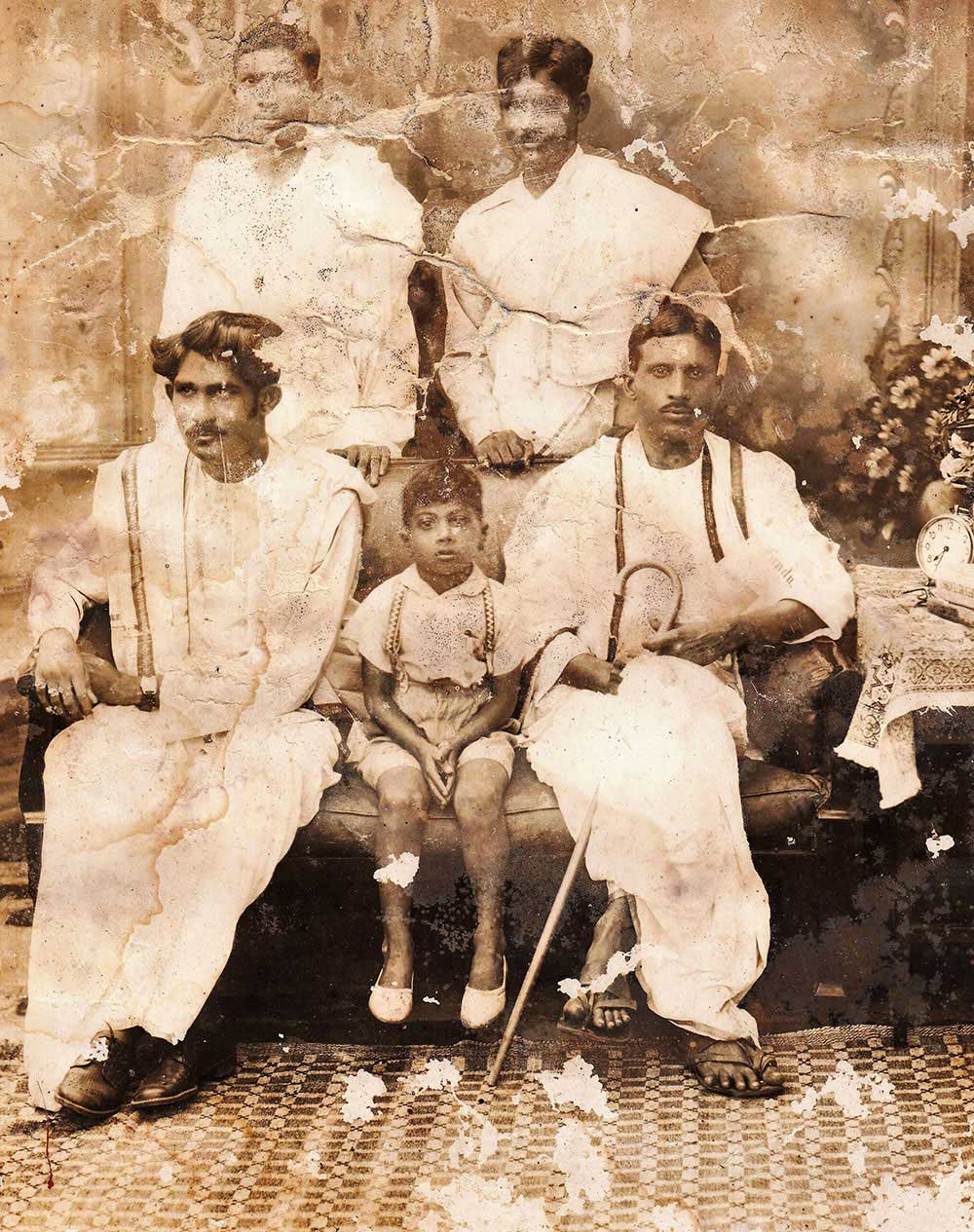

Ten years before India’s independence, in 1937, a little after 7.00 pm, four men and a five year old boy, after some hearty afternoon snacks at a local eatery, seeking novelty, sauntered into a photo studio, in Kakinada – a searing and sultry tropical paradise on the Bay of Bengal – to have their picture taken.

The tall man with a regal bearing, thirty-seven years old, his little son, his teen age nephew, and two friends were from a nearby village, away from the coast, called Velangi. The unknown photographer, sat the little boy to the right of his father on the sofa, between men, and had the nephew and his friend stand behind them for the shot. It was a perfect exposure just past 7.30 pm. Twenty years after that picture was taken, the boy’s father passes away. This rare and only print, hung in my father’s cousin’s homestead for almost a generation-and-a-half. The photograph and the photographer had receded behind the screen of life.

One summer, in the mid 1970s, that five year old from the picture, now a successful man, happened upon it in Velangi. The photograph’s emulsion had fused with the glass, due to extreme heat and humidity in summers, and condensation in the monsoons. And, to this primordial alchemy, came a strange milieu bugs that found the emulsion to be a tasty alternative. Deterioration sped by their way of framing. In India they framed the photographs for “permanence,” an oxymoron, considering the outcome: they mounted the photograph on a cardboard with an acidic glue, then put the photograph directly flush under the glass, without any sort of matting to separate the picture from the glass: the agent of moisture, depending on the season. They then sealed off the back with a tin plate nailed to the frame. Permanent? Yes! But, without any breathing room for the photograph. The result: a slow nightmare that lasts years, in which people appeared to float in a brown miasma, falling away at the edges like a chocolate wafer. This original print, was eventually rescued by that successful man and brought home. He was my father, and the tall man by the table in the picture was my grandfather: Sri Peddada Buchiraju.

This story would be unfinished if I didn’t cover my mother’s side of it, as well! In the 90s, I entrusted my mother with a mission, which is to rescue old photographs that were rotting away on mildewed walls of our relatives in India – that is, if they were ready to relinquish them to our care. I had asked her if there was any photograph of her existing, before she was ten. In 1995, upon a visit to her maternal uncle’s place, she was shown a mildewed, emulsion flaked and moth-eaten sepia toned group photograph on their wall. It was, again, the only print of her older sister’s marriage gathering on the afternoon of May 21, 1943, shot by another unknown photographer. Upon seeing this photograph, she called me promptly and described it. I immediately asked her to acquire the picture, if she could, so we could attempt to restore it.

And restore we did. First, we made a very high resolution scan of the original, it was then converted to a digital file, then, with surgical precision, the photo restorer, went pixel by pixel restoring partially lost faces, and areas in the photograph. He grafted parts of faces in the same tones, borrowed from the adjacent people in the picture – 272 hours later, it emerged as a 11×17 inch print that was simply astounding. Long lost aunts and uncles could be discerned, where there were none at all. My mother and her sisters repressed their dense emotions upon seeing the faces of the long lost ones, their cousins, uncles and aunts, with whom they had frolicked, with deep attachments throughout their childhood.

The photograph’s value to me was supported by three facts: A. many of my long deceased maternal ancestors, whose names I had only heard in the context of something were in it. B. in it also was my mother, sitting obediently, cross-legged on the floor, in the bottom left corner when she was only six. C. a professional photographer was arranged for that specific afternoon. The last point reveals something that is rather astonishing – that, early in the 20th century, even in an ancient agrarian society like India, far away from the cosmopolitan centers, photography had taken root as a business. And, it’s due to the foresight of my ancestors in taking advantage of a new technology, and the intrepid photographic profiteers, I am able to see what my parents looked like when they were children – a world that had vanished long ago. But, this business had indefatigable adversaries, invisible, as well as visible: the brutal oscillation of heat and humidity, and the emulsion devouring bugs of India – where everything, except stone was devoured.

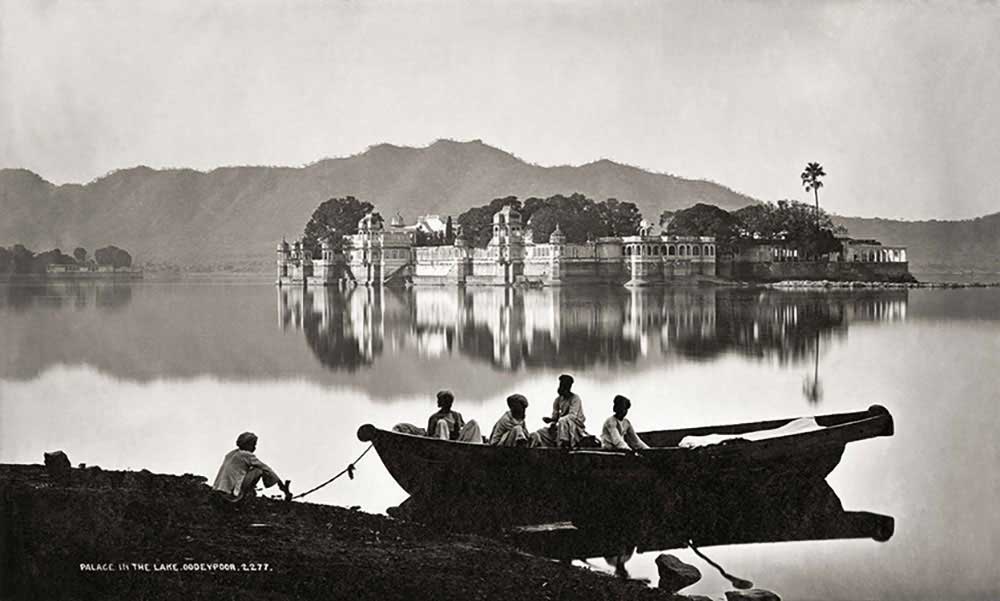

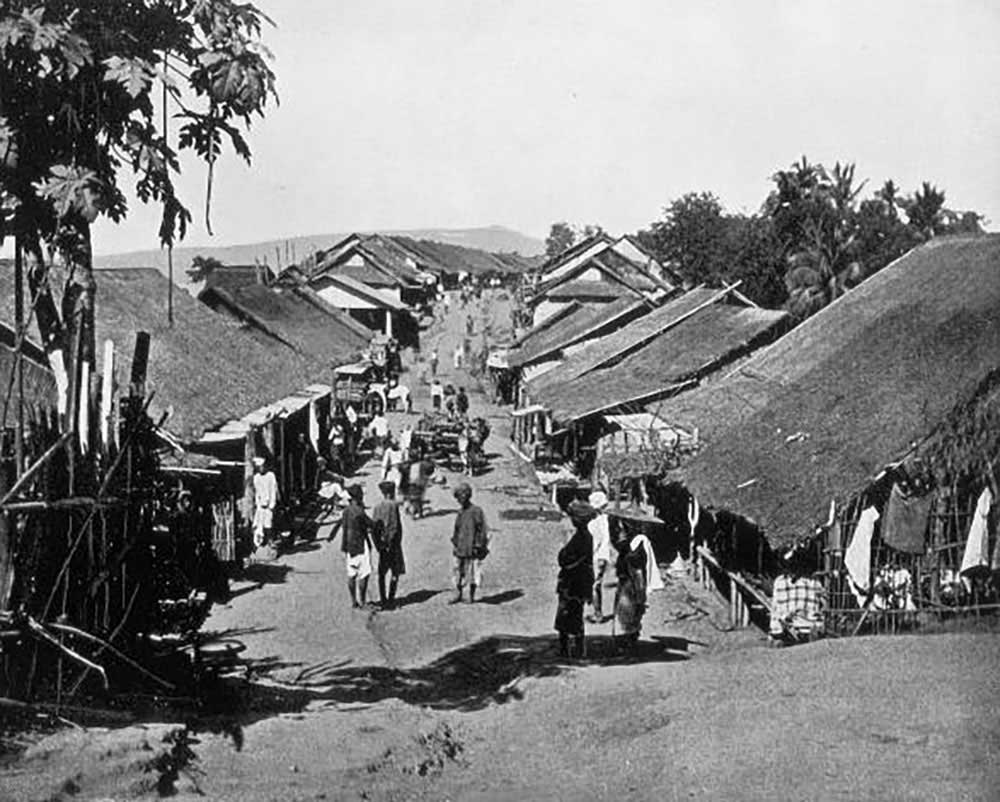

For a long time, photography remained a novelty. It had become an industry in the early-to-mid 19thcentury, thanks to the opportunistic men and women who ventured to profit from it. Arguably, only profits proffer rapid progress in any field. The unknown photographer, is our Unknown Soldier, that has advanced the cause of the industry, with new applications. If Louis Daguerre was the inventor and general strategist, the unknown legions of photographers were his soldiers, that made a profit from our emotional alchemy. As in anything, the one who makes the most noise gets the attention – many practitioners were hustlers, evangelists, in other words exhibitionists. And, a few practiced it as a hobby, quietly, for their own satisfaction. Some were employed by the authorities to record a culture or a colony, as the British did, when they had commissioned Samuel Bourne and an Indian: Lala Deen Dayal, in India.

Many early photographers were traveling showman and adventurers, they were peripatetic men, that found stability in the novelty of photography in faraway places, like Calcutta, British Empire’s eastern capital during the Victorian era. The first recorded experimenter and practitioner of photography in India was a pharmacologist by the name of William Brooke O’Shaughnessy. In 1839, the “Asiatic Journal”and “The Englishman” published articles, describing O’Shaughnessy’s demonstrations, from emulsion prep to releasing the shutter, in Bombay. In the same year, newspapers in Bombay, also published a detailed description of the new Daguerreotype process, followed by the start of importation of this process by Thacker & Co., in 1840. But, it was Calcutta that became India’s center for photography, and the first one to break into the market there was F. M. Montairo, who had brought the process for his studio. In 1849, two more opened studios, H. Schranzhofer and Augustus Roussac, followed by James William Newland, in 1850. During the same period, Julia Margaret Cameron, born in Calcutta, became India’s first Victorian portrait photographer.

All of the early practitioners mentioned here have faded into oblivion, so have the European and American counterparts, who had recorded the industrial revolution on both sides of the ocean. It’s only their surviving negatives and prints that provide us with insights into their industry, aesthetic vitality and passion. A work that required lugging cumbersome equipment to remote regions, overcoming heat, dust, humidity, bugs and thugs, and in most cases, waiting for hours, days, or even months, to capture that one shot that would encapsulate the worlds that have, like them, vanished forever. Their photographs are proofs of their choice exercised in challenging conditions. Essayist, John Berger, posited the code of the photograph aptly: “I have decided that seeing this is worth recording!… true content of a photograph is invisible, for it derives from a play, not with form, but with time.” And, for this very reason, it becomes a handy archaeological tool.

Photography has two intertwined methods of observation, one while recording, and another at retrieval. Besides evocation at a sentimental and rational level, it’s a phenomenal tool for visual anthropology – that assists in the research-&-study of ethnographic data, make detailed studies in the ethnology of various cultures, their transaction psychology, and their material culture – which is another large window into their habits and behaviors. My family photographs are pregnant with personal transactional dynamics, a web of relationships, arrangements, acrimony and feuds. The proximity of where everyone sat or stood in the photograph was entirely based on their personal relationships. In my paternal grandfather’s photograph, the artifacts reveal the influence of the British style: the clock, the English medium newspaper, the linoleum and the Glasgow cotton the men wore that day, the least of which was that western invention they sat in front of – that would make them “permanent.”

As a conservative metric, we shoot one trillion, that’s right, one trillion photographs a year! The photograph is now an ubiquitous default not just for identification, but for communication. We have no idea how many unknown photographers have crossed the threshold from being an amateur to a real artist. Could Daguerre, ever have imagined what his invention had wrought, what it means to the world? The recording and retrieval of an image, is potentially and arguably, one of the three greatest inventions of the 19th century and industrial revolution, the others being the light bulb and the telephone – because the photograph, print or digital, is not just the vector of our aesthetic principles, but means to our memories, information and knowledge.

Finally, Daguerre, the inventor, the theatrical director, and people who had contemplated on this avocation since, never had an inkling that photography would become a psychological tool that would prove, with certitude, that narcissism was intrinsic, fundamental to us, with its core facets of vanity, voyeurism and the desire for immortality, no matter who we were. But, on the flip side, photography’s affect and effect on our psyche is infinitely more than any other invention or discovery. It enables us to deny and obfuscate our ephemerality, the finality of our fate, and helps us to celebrate-and-record what is slipping away from us, as well as evoke moments or memories that had dissolved long ago. It’s an invention that would serve to progress our understanding of all such complex and intriguing human facets. [Copyright © Raju Peddada, July 20, 2018.]

Raju Peddada

Raju Peddada was born in India, and migrated to the United States in 1983. He is the founder and CEO for PEDDADA. COM since 1999, and also a producer/writer for Satyalu+Kristi Media, USA. He is a design provocateur, an originalist in design contemplation, who draws inspiration not from other designers, but from nature, history and literature. He has 22 Design Patents, and was also responsible for several critically acclaimed and sold out products launches to the high end luxury furnishings market. He has been editorially featured in scores of international culture-design magazines as the “Taste-maker,” in Interior Design, Clear, Dwell, Spaces, Domus, Abitare, Interni, Frame, Monitor, Objekt, Chicago, the Chicago Tribune, and Cable news. In addition he also is a freelance journalist, with over a 100 essays-articles- reviews in literary magazines like Swans.com, Bookforum, Spaces, and the NY Times. He is a photographer, who in the summer of 2017, released his exploratory thesis on “The Aesthetics of Ambiguity,” which essentially shifts the aesthetic paradigm, from the stillness aesthetic to that of ambiguity, in sensing the beauty of our movement and condition in the urban setting. Three photographic exhibits are in the offing. He is the author of four small books.