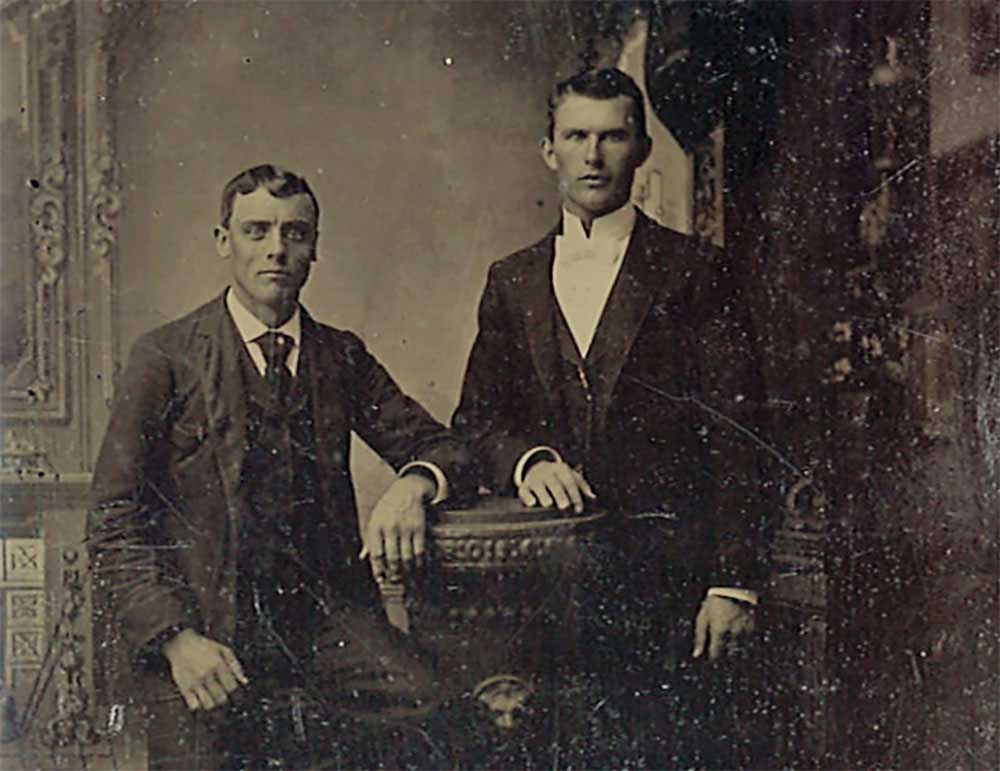

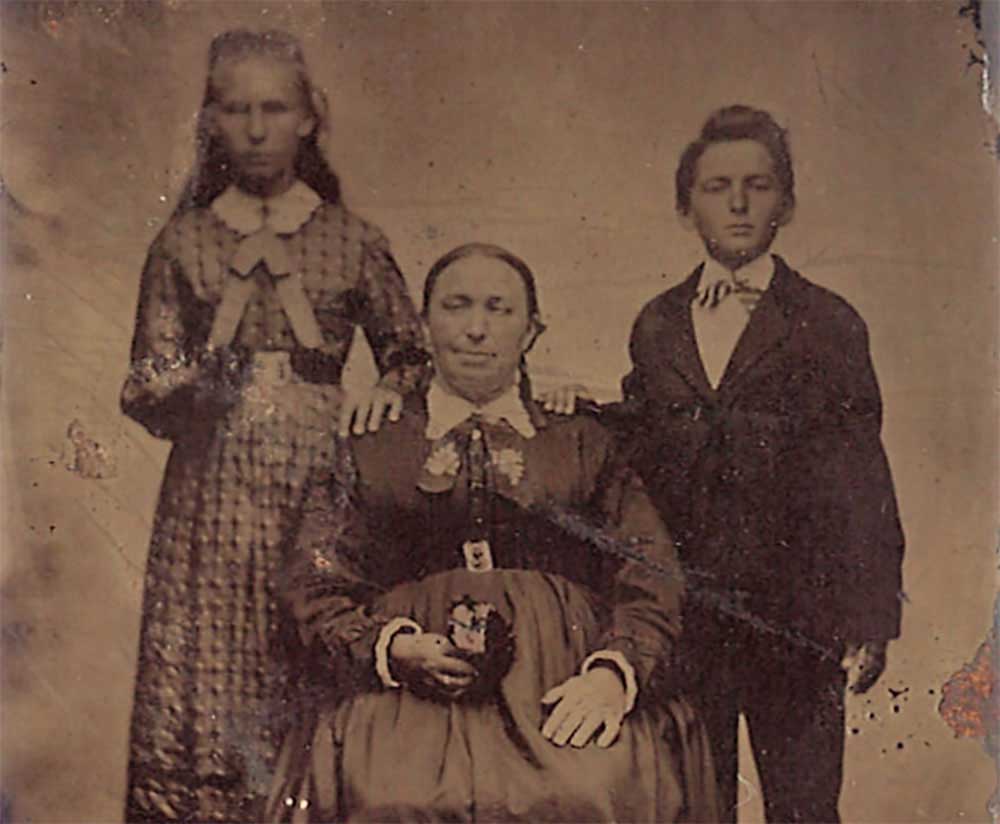

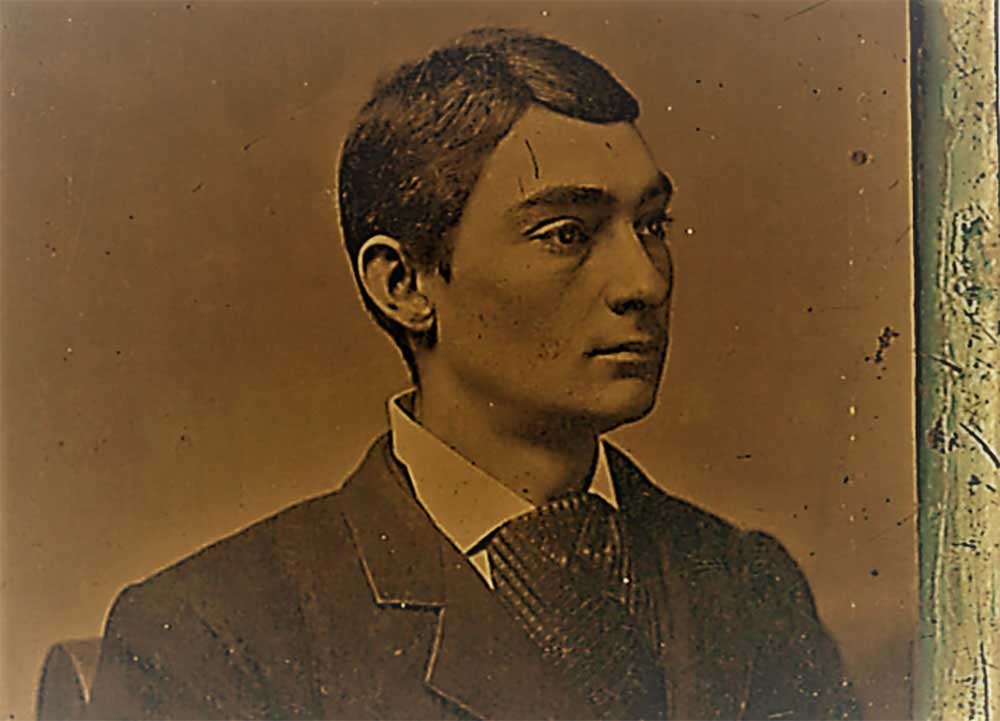

A face is more than just a face. It’s a message board, that offers more than we can read. Or it can be a billboard, revealing the inner most condition.

The face always conveys the compressed energy of life being experienced in a myriad details – that in retrospect, only a fecund imagination and acute sensitivity can correlate and coalesce.

The cryptic countenances divulge, ever so reluctantly, the same internal struggles that we experience daily, in our century. Our fundamental condition remains the same.

Missing in Action

In the late spring morning of 1862, Sam had just turned thirteen. Two yellow butterflies had flitted over his line of sight under the cobalt sky, as three roosters clucked and pecked at the dirt to his left, just as his eighteen year old brother, Tom, opened the gate, and started across their front yard – back from his enlistment, to bid his farewell. As he approached them, his younger brother and his mother, he kicked the pig out of the way, which flipped on its hind, recovered then scurried away in a cacophony of squeals, igniting Sam’s laughter. “Leave some girls for me, will ya?!” a parting ruffle of Sam’s buttery locks by Tom, as he shifted his attention to the bag of food, while avoiding his mother’s eyes. “Come back to us, Tom… my boy…” his mother said in a tremulous voice. “I will… please don’t make it difficult, mother…” That was the extent of their interaction. Then he was gone. Forever.

Sixty years later, in 1925, a tall man with the beard of a mountain trapper, stooped and grim, seventy-three, was hunting for something. He rummaged through a webbed, dusty and decrepit attic of an abandoned building at the edge of town, that once was used for a clandestine telegraph office and photo processing during the war. He swatted away the cobwebs with a newspaper to dig into the pine freight chest in the far corner by the window. He blew off the dust from an object with a flat surface on the top like an anxious archaeologist, when suddenly, a partial face emerged and stared at him with one eye, as if someone peeking from behind a curtain. Howard Carter would have been proud of his reaction. In a concentrated posture, mustering a patience nurtured over six decades of looking, he gently cleared the dust and peered at each photographic plate.

Some were Ambrotype negatives, some were Daguerreotypes, and some were fused. He peered closely at every plate like a seasoned genealogist, looking for triggers for his memory, and it took him to noon to descend to the bottom of the box. Abruptly, a shaft of light cleaved the room, like some omen, as if separating the past from the present with a marbling curtain of agitated dust. At the bottom, under an edition of the “Atlanta Intelligencer” dated May 21, 1864, lay another pile of Daguerreotypes, again, some fused. These were battlefield scenes, hours and days after the carnage. Photographs too dreadful for an exhibit or for the papers. Closeups of distended, decapitated and distorted bodies, beyond recognition, in the process of decomposition, with stray dogs, vultures, coyotes and crows rounding out the anxious diners. In a throbbing interior terror, the legend “Missing in Action” oscillated like a neon hammer in his brain, as he sifted each plate with trembling hands and peered at them closely. He was conscious of his hunt, and wanted it to continue – extend the denial.

Then came the photographs of pathetic negro crews with stretchers shuttling the remains – remains, nothing more than skeletons that had been picked clean, but with uniforms now as rags still buttoned at their nonexistent waists and chests. Then, he saw this plate. A skeleton, whose skull was turned towards the viewer, whose right hand, all bones, extended past the tattered sleeve, and dangled from the edge of the stretcher, being carried by two men. On that hand was an open-end bronze bracelet. The moment of recognition was the decapitation of his being. The braclet had started it’s generational journey on a girl’s wrist in 1698, in Scotland. It was the last thing his dad gave his older brother before vanishing. Stooped and shaking, he put the glass plate down, and in utter deflation, exhaled a repressed sixty year old sob.“Why can’t I be spared, why?” The man had lost his brother twice. No likeness remained of him, except a fading one in his mind, from when he was thirteen. He then picked up the glass plate and compressed it to his chest in a paroxysm of anguish, shattering the plate and shredding his ulnar artery – he died three hours later. A demolition crew found his remains, picked clean, thirteen months later.

The Greatest Generation

Over six-hundred thousand boys and men from the Industrial Revolution had perished, and more than a million such stories vanished altogether, replete with singular dramas, to a lesser or a greater extent. When I look at their faces, I can conjure up their loves, their disappointments, their labor, their trials and their triumphs – faces tell more than we could fathom or care for. And, they are in the form of Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes and Tintypes, during the entire span of the late industrial revolution in America. Ironically, most life altering discoveries and inventions came within twenty years after the war, and many modern weapon systems, still in use in the 21st century, had been invented during the war. Trauma was not allowed triumph, under any circumstance.

People suffered through unimaginable personal devastation, yet, they coped, survived and became the generation that gave us electricity, the light bulb, the telephone, the car, manned flight, photography, and the dignity of a working life. I cannot help, but think about the young “adults,” in the 21st century at our institutions of higher learning, that threw destructive tantrums and huddled and wept in safe spaces, some requiring psychotherapy, all because, the opposition had won the elections. What would the people of the late Industrial Revolution, who had fought the Civil War to rid us of Slavery and preserved the Union, then went to wring American exceptionalism, think about it. I would hazard to bet, that they would die in side-splitting laughter, like Sam did, when his brother had kicked that pig to his left.

The Greatest Invention?

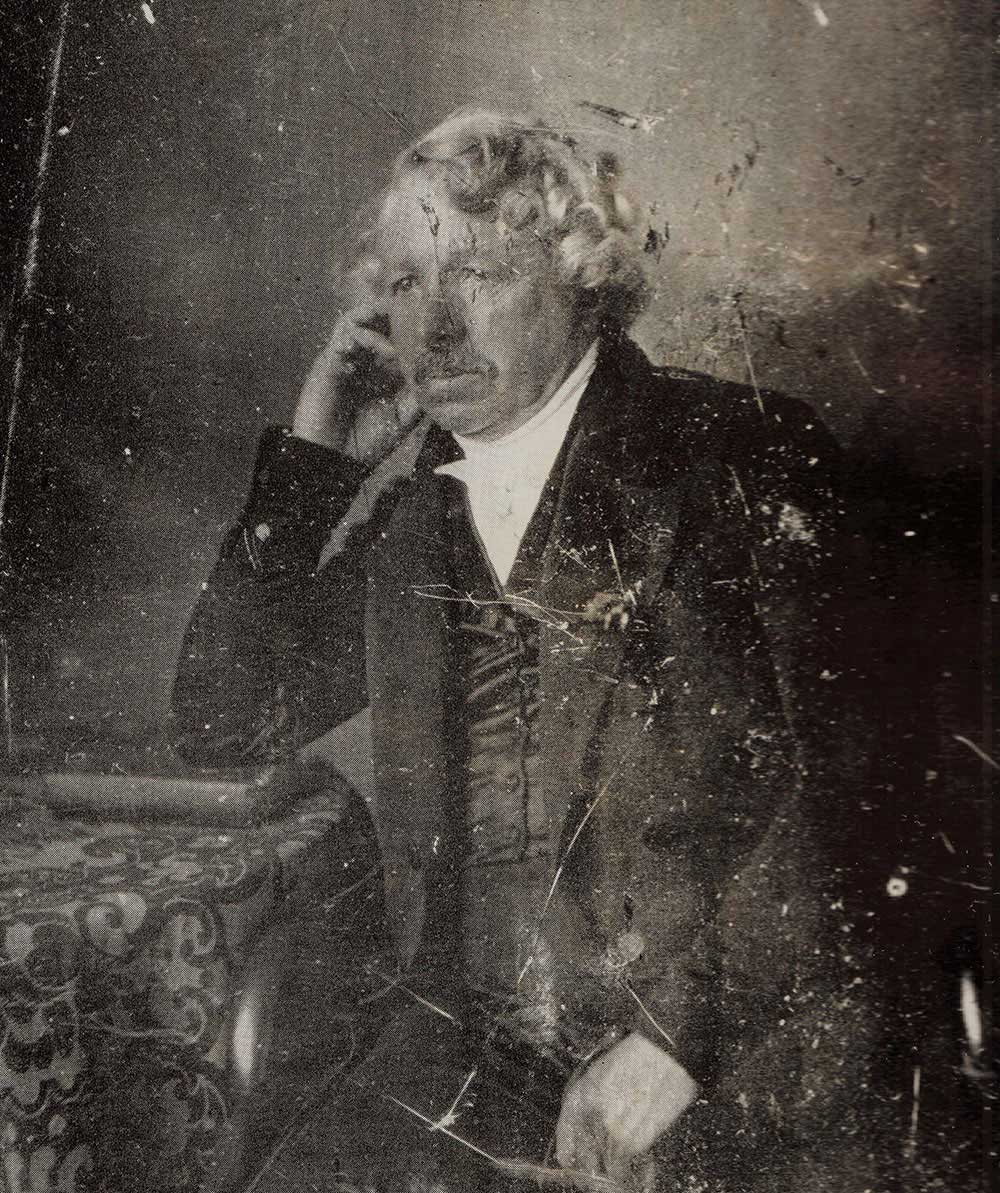

Of all the inventions of the 19th century, photography, the earliest of them, is probably the most underrated one. Daguerre’s invention of Tonal-Realism in 1833, actually took root in the United States after Samuel Morse, brought the apparatus and technique after his stay in Paris. He was instrumental in bringing two century altering inventions back from Paris, his own: the telegraph and it’s operating premise: the Morse Code, the second was the Daguerreotype process. Both these inventions and their processes brought applicable technology and immediacy to their communications: the realistic image and real time messaging. And, the Civil War was the event that fertilized both these inventions – both technologies came off age during that very American bloodbath.

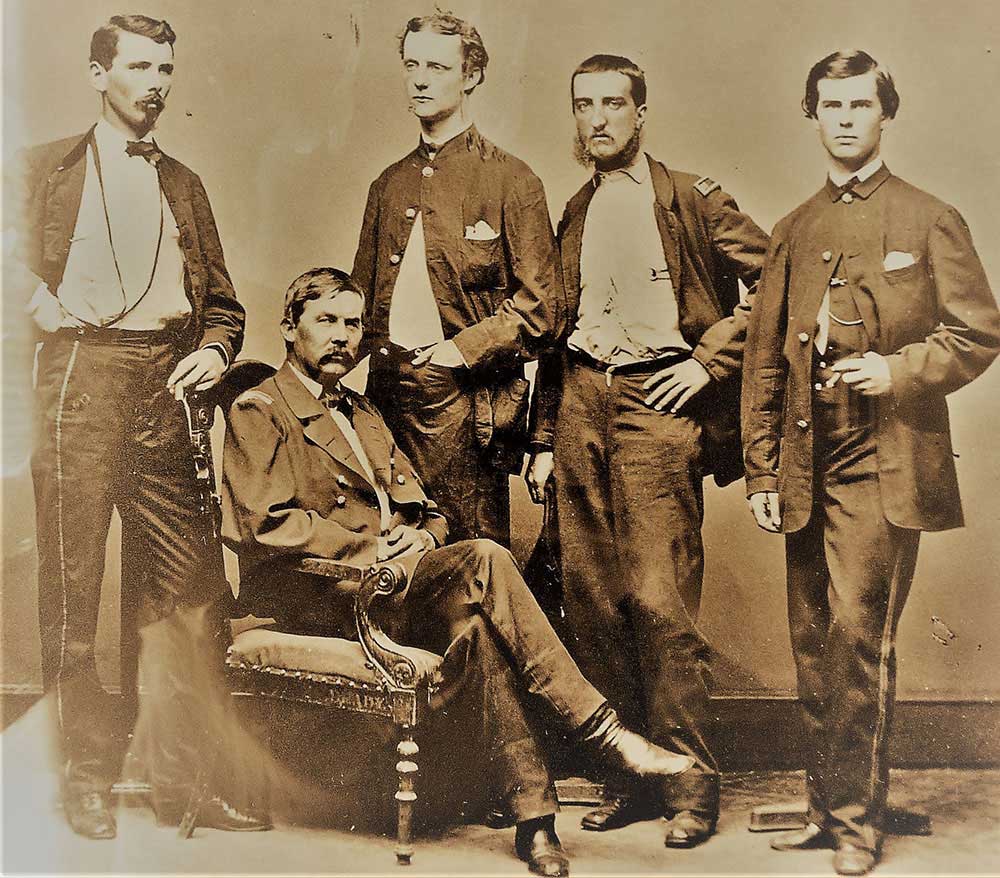

The American Civil War (1861-65), was fought by the people of the late Industrial Revolution. It was the first large scale war that was recorded in its entirety, by photography. The war, ironically, nourished photography in unthinkable ways, enabling it to become a societal and industrial necessity by the end of the war. In the eras past, wars were depicted in illustration and paintings, often glorifying or romanticizing it – keeping the torn bodies, decapitations, and holes for faces at bay, in the illusions of glory. But, photography changed all that, it destroyed our denial and replaced it with our culpability. In fact the earliest exhibits in New York and D.C., the ones by Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner, simply shocked audiences and fueled passionate sentiments against war. They soon learned that photography is the practice and art that debilitates the concept of deniability, by rendering the reality manifestly inexorable, implacable. This type of visual aftermath ushered in a new typology of trauma, a sort of PTSD for the viewer – images fetched extended contemplation, brooding, reliving, fear of the possibility of such unfathomable gore, and the depression that followed in its wake.

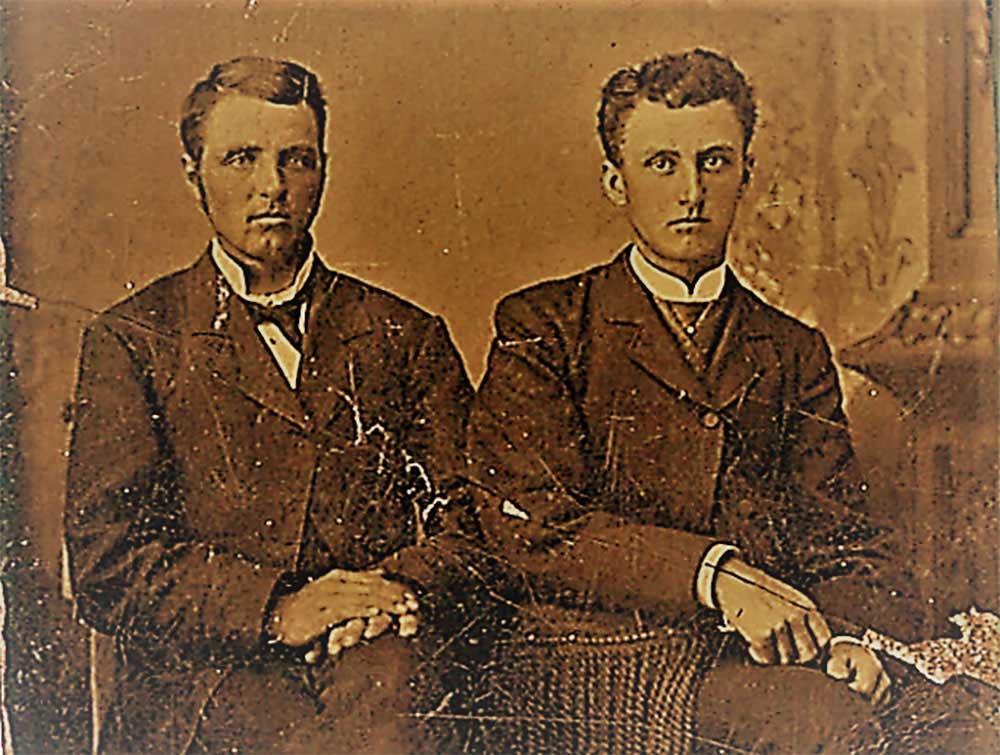

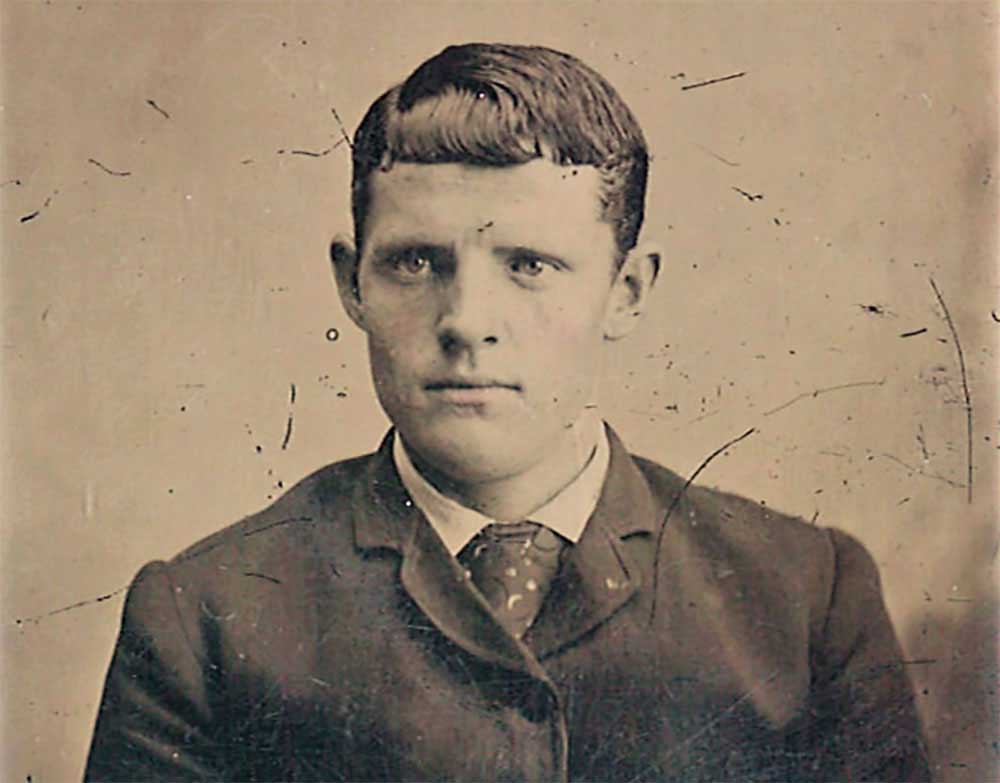

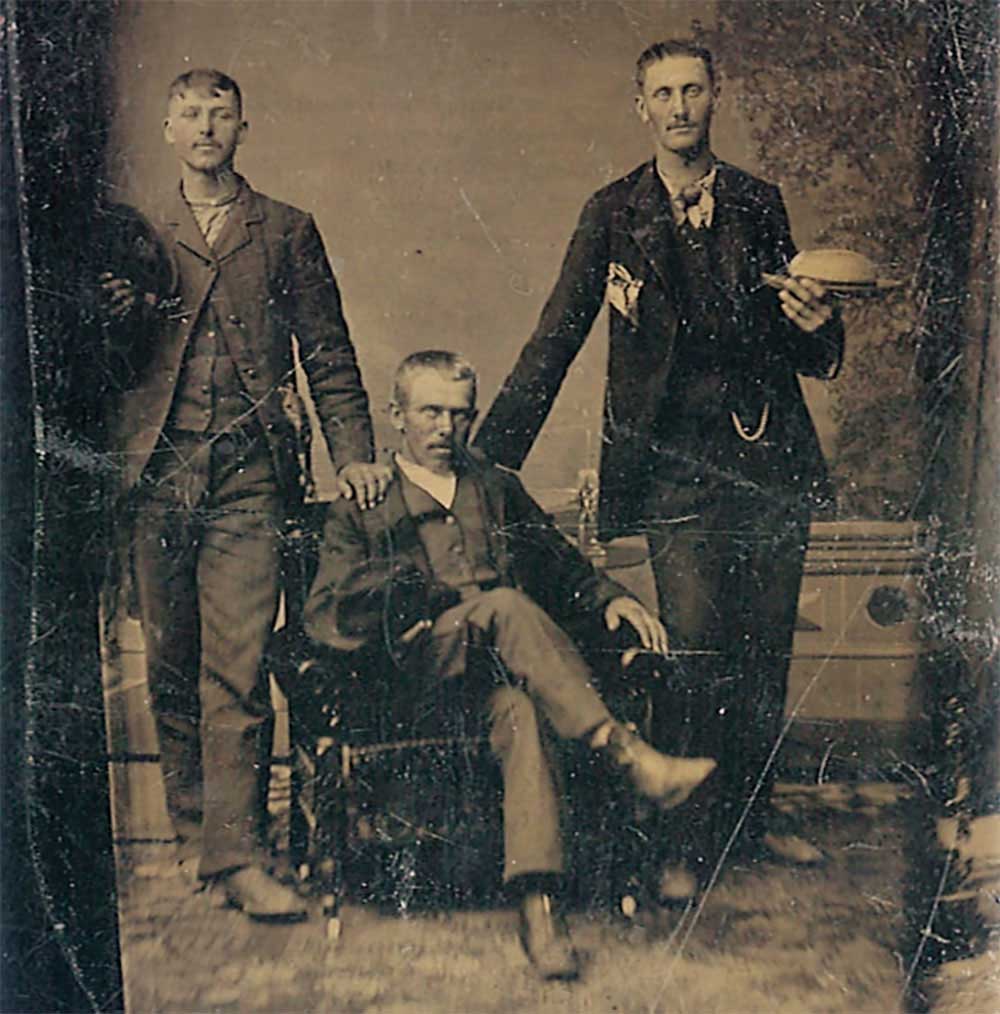

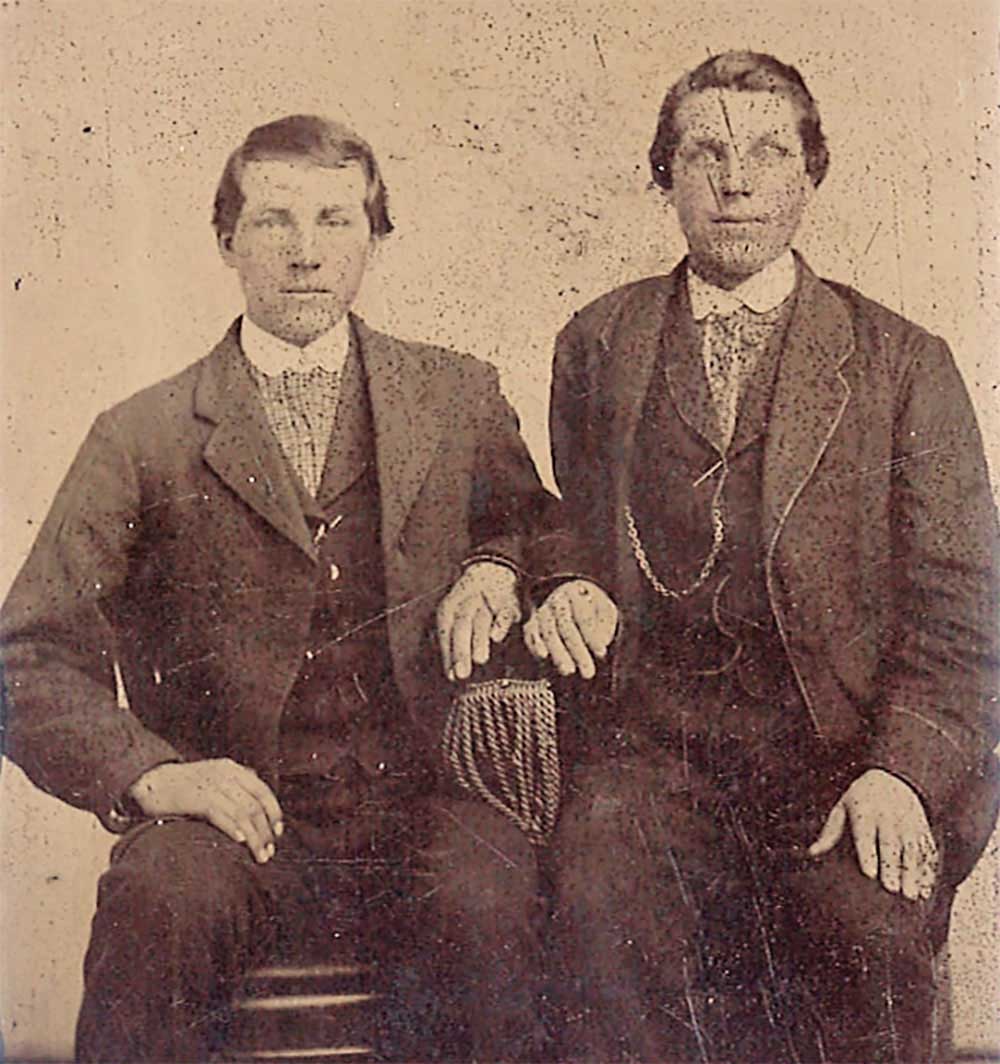

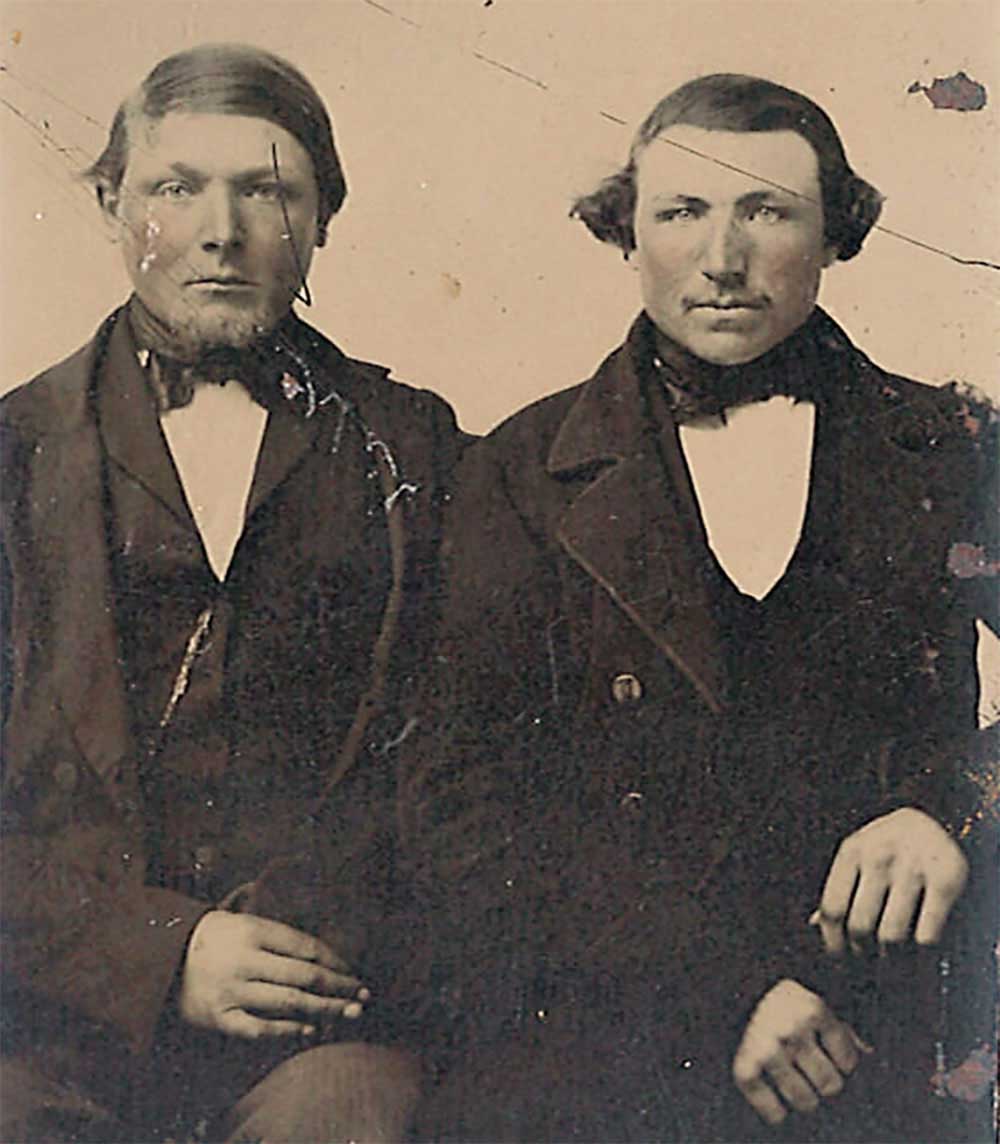

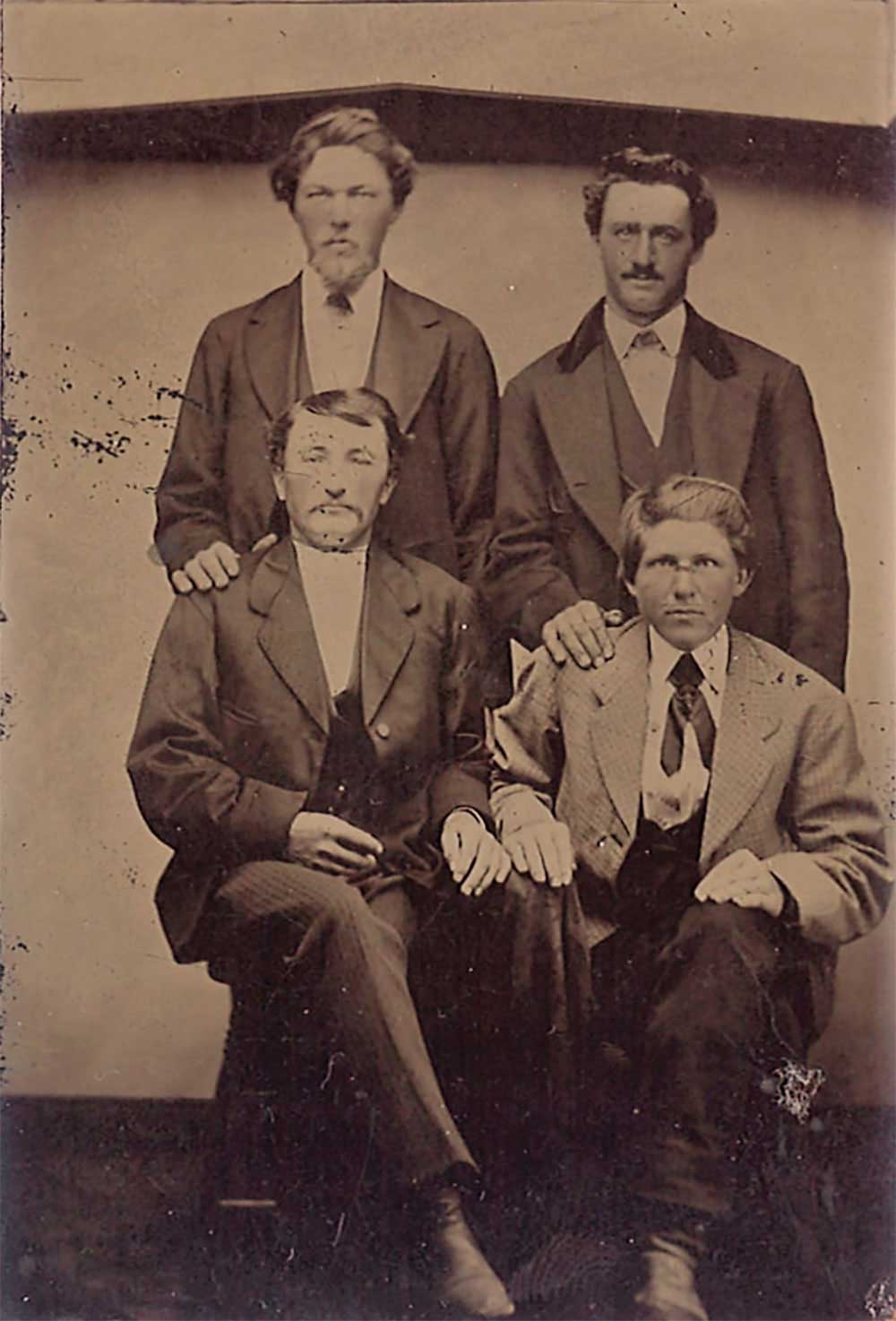

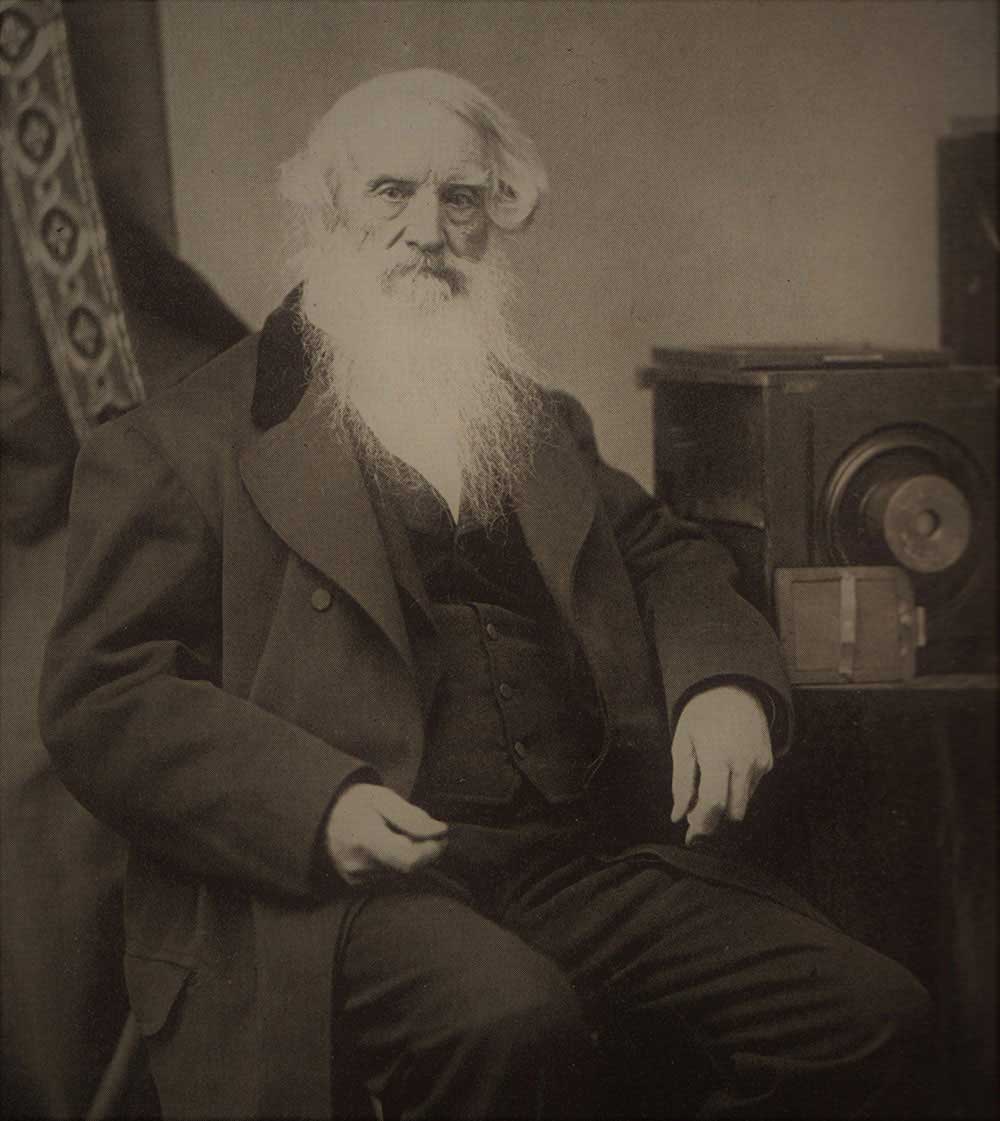

The rare Tintypes preserved and presented here from my collection, are, reversed postures, they are flipped, which is inherent to such plate development processes, and cannot be detected. While the glass plate sizes from the Daguerreotype or Ambrotype processes came in standard sizes, the Tintypes were cut out metal plates, sometimes cut in weird shapes and sizes, mostly within the postcard size – that appeared as anachronistic metallic Polaroids. After the war, big studios grew their business by sending hired photographers into the field, who plied their trade in distant rural settings, recording the nation as it grew out of its agrarian roots to planted steel buildings and bridges. While in the city, the studios indulged occasional celebrities, like Senators, society woman, and even presidents. Lincoln was the first iconic president to be regularly photographed. What these traveling photographers and their subjects left behind was a treasure trove of aesthetically charged photographic plates, in their melancholy patinas and distress, with portraits that took abuse for over a century-and-a- half, in the form of scrapers and coasters, and still told intriguing tales.

Finally, Why I Collect

I always experience chills and freeze, peering at these peculiar faces that talk to me. “I am no different than you are… same pursuit for happiness in dysfunctional relationships, hardships… headed for oblivion.” My friend, a Tintype expert, asked, “Do you know why they look so grim, like someone they knew was dead?” While I guessed he continued. “It took the photographer a long time to set the camera and flash, and by the time the photographer was ready, they had lost all their spontaneity, humor and turned somber, like in a funeral, in their black outfits.” Who were they? It was quite ironic that the folks on these plates, with their fleeting lives, were captured by some unknown photographer, who had confiscated their frolicking anonymity, replacing it with a punishing immortality no cares about.

Finally, there’s no such thing as an insignificant Daguerreotype, Ambrotype or a Tintype photograph. Every photograph of a person, from the early through the late 19th century America, represented a piece of the evolving national puzzle. Such photographs are indispensable shards of our national memory, our collective western heritage. These photographic processes were a powerful soliloquy on the progress of the medium itself. This is where reality got ossified into a metaphor, and the osmosis of photographic emulsion to blood, as a fact, as proof. These old distressed photographs transcend their own medium to become our meditation, on the universality of suffrage and the temporality of life itself. Look into their eyes, linger there for a while and see if you can make a friend, that would tell you a story. Your own story. [Copyright © Raju Peddada. All rights reserved on the Text and photographs.]

Raju Peddada

Raju Peddada was born in India, and migrated to the United States in 1983. He is the founder and CEO for PEDDADA. COM since 1999, and also a producer/writer for Satyalu+Kristi Media, USA. He is a design provocateur, an originalist in design contemplation, who draws inspiration not from other designers, but from nature, history and literature. He has 22 Design Patents, and was also responsible for several critically acclaimed and sold out products launches to the high end luxury furnishings market. He has been editorially featured in scores of international culture-design magazines as the “Taste-maker,” in Interior Design, Clear, Dwell, Spaces, Domus, Abitare, Interni, Frame, Monitor, Objekt, Chicago, the Chicago Tribune, and Cable news. In addition he also is a freelance journalist, with over a 100 essays-articles- reviews in literary magazines like Swans.com, Bookforum, Spaces, and the NY Times. He is a photographer, who in the summer of 2017, released his exploratory thesis on “The Aesthetics of Ambiguity,” which essentially shifts the aesthetic paradigm, from the stillness aesthetic to that of ambiguity, in sensing the beauty of our movement and condition in the urban setting. Three photographic exhibits are in the offing. He is the author of four small books.