I began making urban landscapes in Los Angeles in September of 2001, in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks in New York. In those upside-down times, I used a $20 plastic Holga to photograph my grief, horror and alienation in the LA’s many strange neighborhoods.

That crappy camera can barely see straight, and I suspect I was using it to negate the act of photographing even as I pursued it.

Six months later, I took my bag of Holgas to New York to photograph the light- sculpture at Ground Zero, where the fallen towers had been re-imagined by huge banks of movie-premiere spotlights, shining skyward in two brilliant columns. I spent the long evening of my 42nd birthday in the snowy streets of Lower Manhattan, dragging tripod and cameras in slow circles around those luminous ghost-buildings.

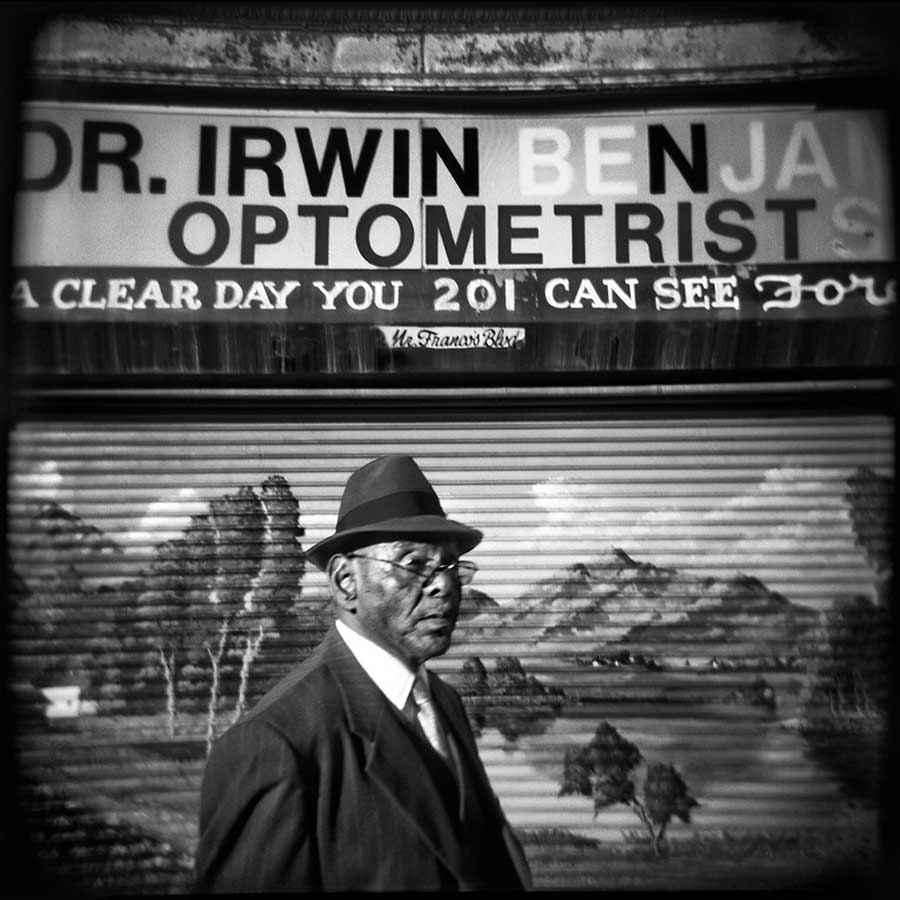

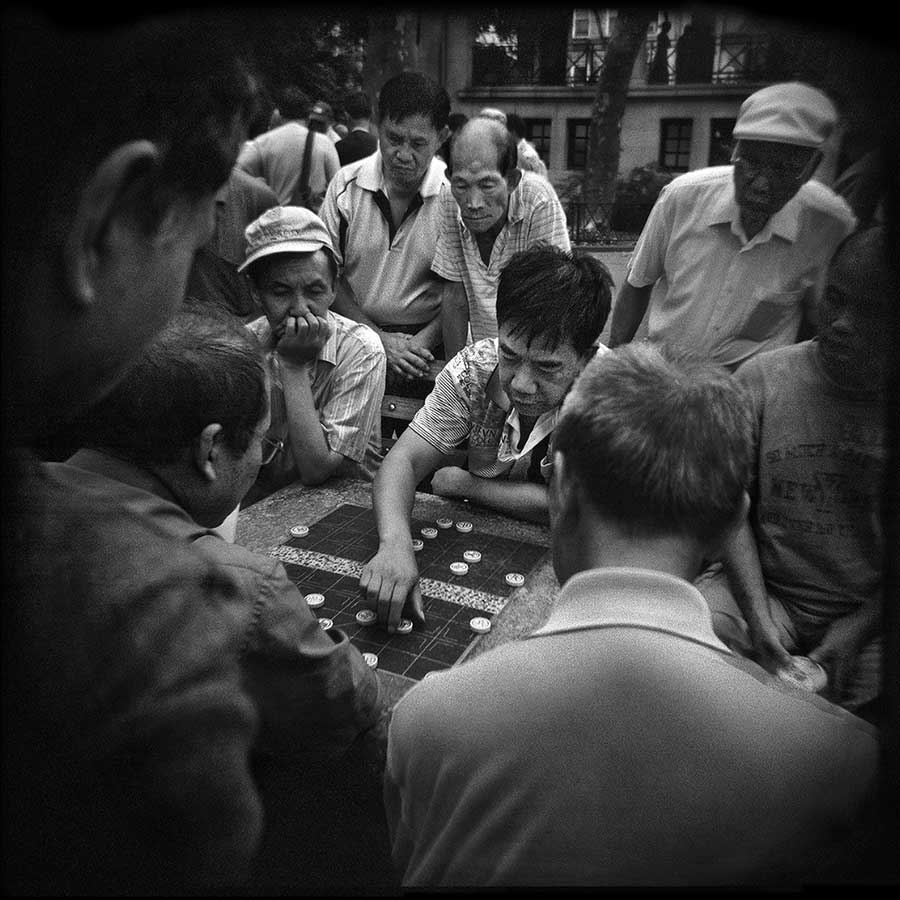

During twenty-plus trips in the ten years since that freezing spring evening, I’ve shot more than 1200 rolls of film in New York. Walking all day in Manhattan’s great brick canyons, I’ve learned that the staple heroic views of soaring architecture are all present (and very seductive), but also that there are fresher, more colloquial pictures to be made. Surprising details (great and small, poignant and ironic) leap into focus when one’s gaze resorts to the human scale—and that screwy, benighted Holga is certainly human scale, though “focus” is barely within it’s primitive capabilities.

Many of these New York pictures are populated by artifacts of American ambition in the nineteenth century, and the great landmarks of 20th century achievement: the buildings, statues and bridges that were all the first of their kind, and which spoke, in their day, of ingenuity, resource and will to an awestruck world.

Photographing this project, I’ve watched contemporary New Yorkers struggle to navigate the long shadows of that golden era: every day these modern folk—with their own ambitions for control of this physical space—must confront the towering indifference of that grand old city, which is truly set in stone. They bang their machines against those edifices to reshape them, and bore into them like termites, stringing fiber optic cable and broadband, while the city merely twitches and sighs, and watches this age-old business with a single cold eye, alert but unimpressed.

About Thomas Alleman

Thomas Alleman was born and raised in Detroit, where his father was a traveling salesman and his mother was a ceramic artist. He graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in English Literature.

During a fifteen-year newspaper career, Tom was a frequent winner of distinctions from the National Press Photographer’s Association, as well as being named California Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1995 and Los Angeles Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1996.

As a magazine freelancer, Tom’s pictures have been published regularly in Time, People, Business Week, Barrons, Smithsonian and National Geographic Traveler, and have also appeared in US News & World Report, Brandweek, Sunset, Harper’s and Travel Holiday. Tom has shot covers for Chief Executive, People, Priority, Acoustic Guitar, Private Clubs, Time for Kids, Diverse and Library Journal.

Tom exhibited “Social Studies”, a series of street photographs, widely in Southern California. “Sunshine & Noir”, a book-length collection of black-and-white urban landscapes made in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, had it’s solo debut at the Afterimage Gallery in Dallas in April, 2006. Subsequent solo exhibitions include: the Robin Rice Gallery in New York in November 2008 and March 2013, the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR in October 2009, the Xianshwan Photo Festival in Inner Mongolia, China, in 2010, California State University at Chico in 2011, and the Duncan Miller Gallery in Los Angeles, February 2013. Finally: Fifty-three of Tom’s photographs of gay San Francisco, shot between 1985 and 1988, debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December, 2012, under the title, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws”. [Official Website]