As I pulled away from Mom and Dad’s condo, I looked back one more time and snapped two photos of Mom as she waived goodbye from the sidewalk. She was fully dressed, her cheeks noticeably hollow and her expression strained and apprehensive.

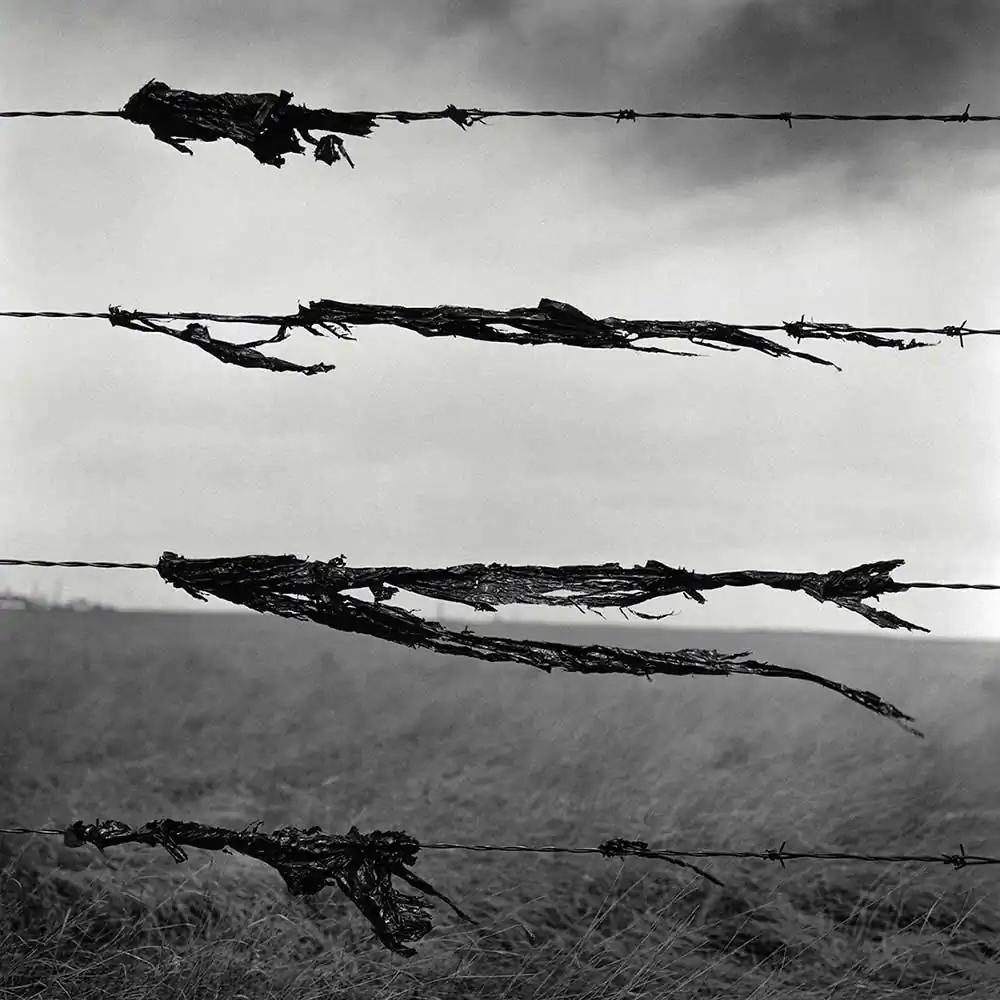

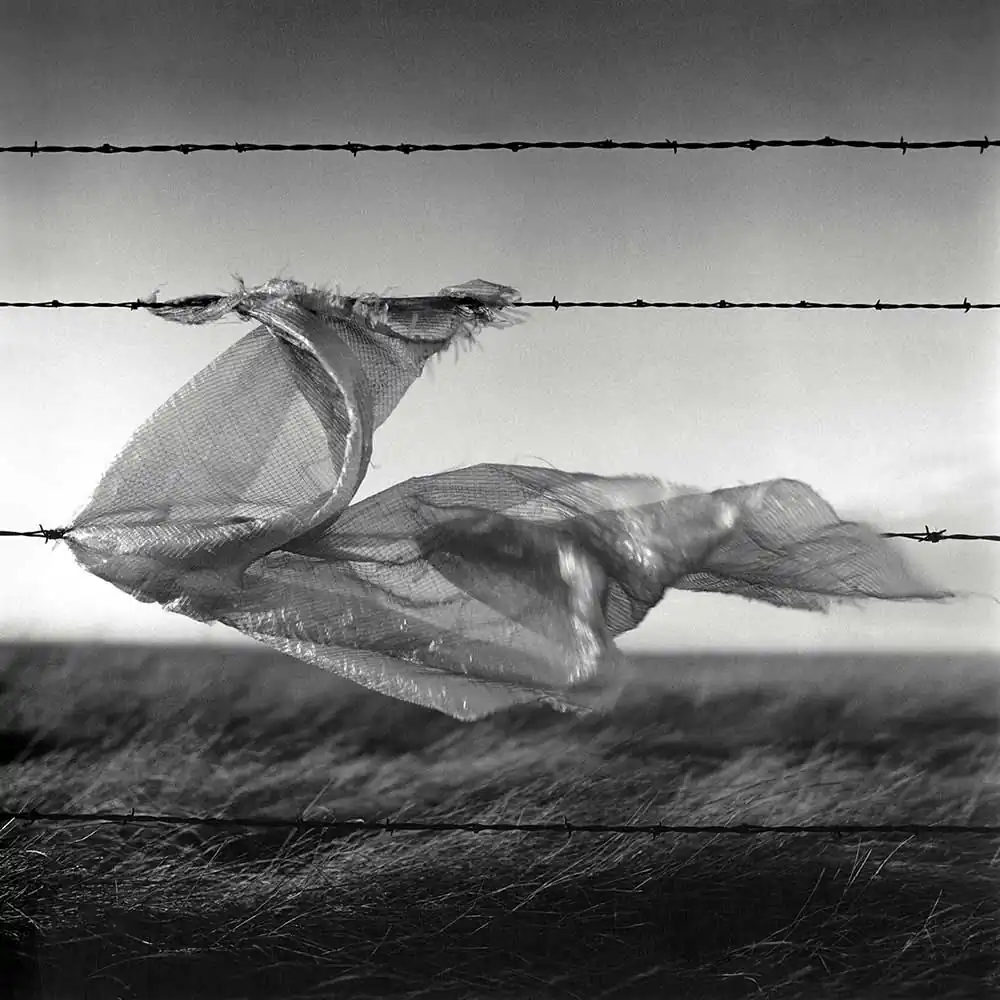

Heading west on the Trans-Canada Highway towards Calgary, I soon passed Redcliff. It was a typical sunny and blustery September morning with the prevailing westerly winds howling across the flat prairie landscape. The traffic was minimal. As if my head was forcibly being turned by the unrelenting gusts, I became distracted by the flapping remnants of plastic bags caught in barbed-wire fences.

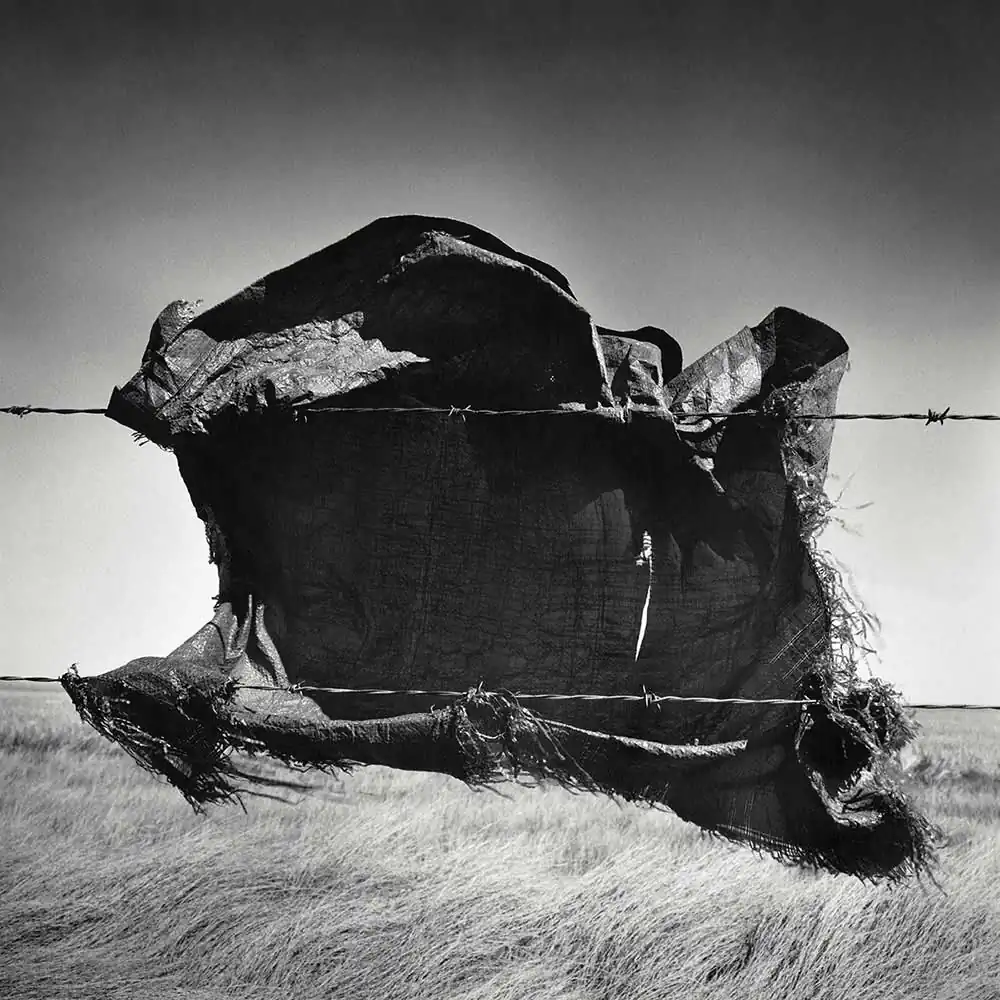

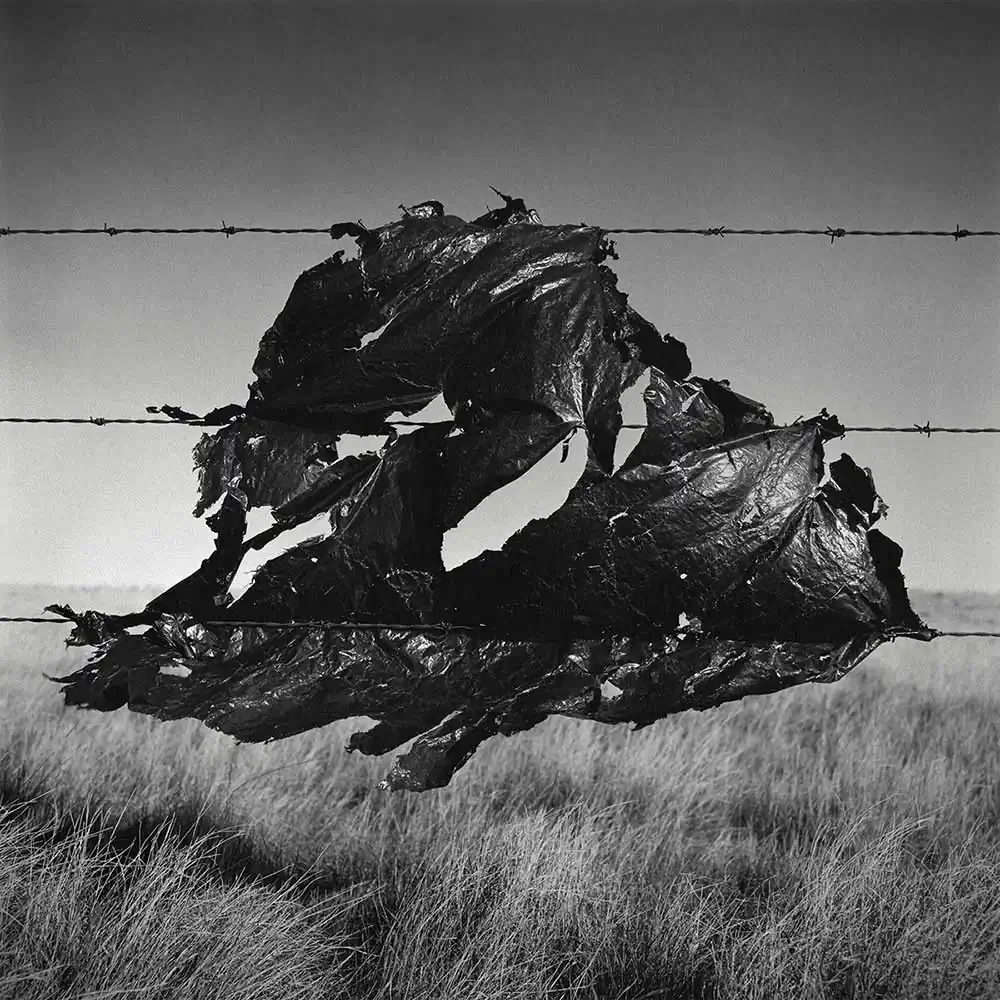

Mile after mile, the fences that lined the ditches were embellished by these forgotten shreds of plastic that were being violently whipped by the wind. They appeared to be trapped in the no man’s land of boundary fences, neither here nor there, an emotional purgatory. Frayed, lacerated and punctured these ubiquitous objects drew me in. I stopped the car. Later on my flight, I would open my photo album on my phone many times and view the images I had shot along the highway. My curiosity for these often-unseen objects grew. Arriving home late, I uploaded them onto my computer and changed them to black and white. My heart sunk in sadness and reflection.

Seven weeks later Mom passed away. In 2015, I returned to the ditches and fence lines on the edges of highways and county roads of the windswept scene of Southern Alberta to photograph these objects in the plain, seasonally muted and monotone wide-open spaces where the environmental forces are a harsh reality. Over the next three years, I would expose 108 rolls of black and white film while photographing the plastic ruins. Not relying on my sight but on my sense of touch, I developed the film in complete blackness. There was also another darkness that I was coping with – the loss of a loved one.

When film is exposed in a camera, a latent image is made and it remains there until it’s brought into contact with the developer. The image becomes visible only after it has been treated with a fixing agent, densenitizing it to light. Like in science, many things lay dormant in our lives until activated by the right combination of events or circumstances. Given the physical process of the plastic’s decomposition, it was critical to the logic of the photographs to maintain the immediacy of their chemical, indexical imprint on the film, and its translation onto photo paper, creating a substantial presence that would have been impossible to achieve digitally. A real hug beats an emogi. Moving from working in total darkness to the red amber ambience of the darkroom’s safelight brought therapeutic comfort and warmth. The choice of nostalgic music from the 1960’s and 70’s also often enhanced the chemically saturated air. Perhaps it was a yearning to return to the past when things seemed better.

I often felt the physical warmth of the mid-afternoon sun on my back as I as knelt in the ditches behind my camera and tripod. I would pre-visualize the final photograph, compose it in the viewfinder, anticipate its motion, look for the pinnacle of its expressive form and press and release the shutter. Over sixty-eight sites were photographed. Some locations required multiple visits to ensure the optimal lighting and wind conditions.

In this series called Snag, the photographs are deeply rooted in loss, mortality and remembrance. Our eventual passing is universal. It does not provide an opportunity for any of us to opt out of. The scenes are simple and ordinary. Based on isolating and elevating the unseen, the photographs contain the past, the present and the future. On one level what the object was, what it is now, and what will it be in the future or more thought provoking…who was I in the past, who am I now, and what will come of my own mortality.

The photographs at first sight are physical, material representations of a reality. However, the “optical unconscious” as described by Walter Benjamin, a critcal thinker, permits us to see things we normally would not be sensitive to. It allows us to access a part of the mind containing feelings, desires, images and ideas not always available for direct analysis. Attuned to the impermanent, ambiguous and abstract nature of life, the plastic becomes a metaphor for mortality, pain and death while unearthing repressed feelings of fear and anxiety.

The ephemerality and fragility of life is reinforced through the struggle of the plastic as it fights to free itself from its entanglement in the unforgiving barbed wire. In contrast there is beauty and poetry in the ballooning ragged forms as if their lungs are taking one more deep breathe in hope of physical or spiritual deliverance. The uncanny photographs of Mom waving goodbye remain unprinted and are only code in digital files. The photographs haunt me and yet hold so much beauty. I can’t look at them often but when I do, it’s as if Mom was a world away already on that last day I saw her alive. They are so personal. In all honesty, the photographs of my Mom wouldn’t have meant much to you. You didn’t know her.

I hope that by unraveling Snag, that you too will take the time in your daily habitual lives to elevate your curiosity, to find the hidden beauty that surrounds you in the most common places, allowing your observations and your emotions to ignite a new found understanding and excitement for this precious although transitory celebration we call life.

Artist Statement

Five years ago, I was leaving for the airport after saying goodbye to my mother. She was dying of cancer. On the long drive across the windblown Alberta prairie, I found myself distracted by flapping remnants of plastic bags, caught in barbed-wire fences that lined the ditches. Whipped violently by the unrelenting wind, they were left shredded and lacerated, but trapped nonetheless in the no man’s land of boundary fences, neither here nor there, an emotional purgatory. Thinking about mortality, pain and death in the context of my mother’s terminal illness, these forgotten shreds of plastic took on a deeper significance. Snag.

Shooting during the seemingly lifeless seasons between winter and spring in 2015 through 2017, I photographed over sixty-eight sites in Southern Alberta, Canada. Some locations required multiple visits to ensure the optimal lighting and wind conditions. All the photographs were shot using black and white analogue film in a medium square format camera. Given the focus of the subject matter on physical, material processes of decomposition, it was critical to the logic of this series to maintain the immediacy of their chemical, indexical imprint on the film. Its translation onto a slightly warm toned fibre-based photo paper creates a material, substantial presence that would have been impossible to achieve digitally.

About Wes Bell

Wes Bell was born and raised in Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada. From an early age he was fascinated by art, which led him to the studio-intensive program at the Alberta College of Art and Design, where he received his Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography.

After school he pursued a career in fashion photography. Bell lived and worked in Milan and London, eventually relocating to New York, while travelling extensively on assignments to the far corners of the world. His acute sense of design, style and aesthetics are highly respected by fashion editors, leading to editorial spreads in publications such as British GQ and Esquire, Conde Nast Traveler, The New York Times Magazine and People. Celebrity portraits include Channing Tatum and Olivia Wilde, as well as fashion designer/film director Tom Ford.

After residing in New York for more than twenty years, Wes returned to live in Medicine Hat four years ago. Since departing the fast-paced world of freelance fashion photography, he has reignited his passion for fine art photography, and today photographs in both the studio and on location, responding to the detail and natural beauty in the environments that surround him.

Bell’s dramatic black and white photographic series Snag, has been exhibited internationally in both solo exhibitions and in numerous group shows, including Rfotofolio’s 2018 Depth of Field Exhibition at the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, California. He is the recipient of the LensCulture Exposure Awards 2017 – Jurist Award as selected by MaryAnne Golon, Director of Photography at The Washington Post. He also received the 2017 Bronze Award for the Royal Photographic Society International Photography Exhibition 160 in the United Kingdom. He is currently working on a book project called On the Line, which includes five inter-related series: Lost for Words, Final Steps, Rapt, Snag and In Plain Site. [Official Website]