If you want to discuss the atmospheric void above the Earth, you don’t have a great deal of choice. A short, unprepossessing word stands out: sky.

So it’s clear (and the child saturating the top of a page with a blue felt-tip is giving a colourful demonstration of the fact) that this is what opens up to one’s eyes, if one just raises them for an instant to contemplate the immensity that’s displayed there without reserve. Language sometimes has surprises in store for us. And in its most ordinary, immediate acceptation, sky – the word, as much as the “thing” – may be self-evident.

But moving on to the plurality of skies surreptitiously directs thought towards horizons that aren’t of the same kind. One senses that, in reality, the consequence of the shift from the singular to the plural isn’t so felicitous. It bifurcates. Still, there’s nothing surprising about this, given that the meteorologist’s skies, as we know, don’t overlap or intersect with those of the astrologer, any more than those of the classical painter do with the heavens of the theologian. Here, as always, the choice of word, inflected by singularity or plurality, has its importance. Words summon up worlds they invent as they’re spoken; so that number does not, perhaps, denote the thing you thought you were seeing, but rather brings out, with and despite it, the set of determinations that tacitly sustain it, beyond vision. And so you have to wonder, abruptly, what you’re seeing, and what, indeed, you’re talking about.

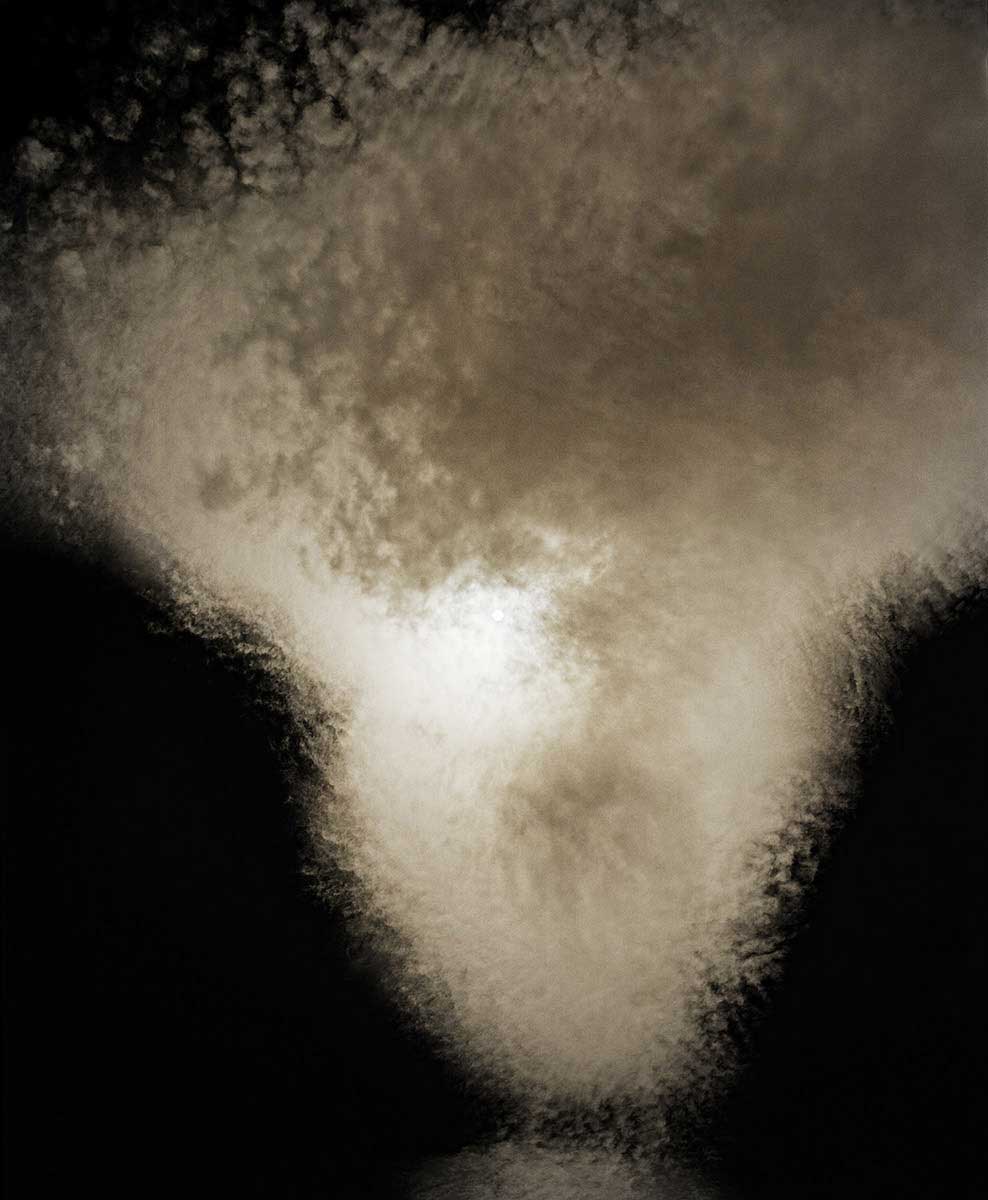

Eric Bourret’s a photographer, in that for years he’s been doing what this activity presupposes. He thinks up, and produces, images. The motif in those he’s presenting here makes reference to what might rightly be called sky, given that, in imposing, stupefyingly beautiful formats, the sum of its attributes can be seen: the void, and the clouds, complex, often milky, that arrive at random to fill it up. And at their heart, an enigmatic hallmark: the focal, discreet light of a cold star. But Bourret is also, if not first and foremost, or essentially, a walker, in other words someone who unceasingly goes here and there, moving around, eyes wide open, indefatigably ranging over territories, many of them distant. And what’s more, he’s a high-altitude walker. Which is not just incidental, quite the contrary: it’s certainly in relation to this inveterate action – walking in the mountains – that we have to approach, see, look at, contemplate the photographs. It would be vain to try distinguishing between that which stems from research one might consider to be solely aesthetic and that which has to do with a memory of physical experience; which involves the corporal materiality of the subject Bourret becomes in traversing the heights, sure-footed, heart beating, breathing. Or, to put it another way, we’re not looking at, on the one hand, a “technicist” using an optical prosthesis – a camera – and, on the other, someone equipped with the paraphernalia proper to the amateur explorer of seracs, firn, frost-scorched uplands, summits. The seeing and the walking are inextricably linked; everything’s correlated. But we also realise, very soon, that these two dimensions, which attest, in particular, to a way of being in the world, a sort of ethos, continuously call upon each other in a sort of chiasmus. Looking at the photos, we understand that these modes of action operate together; that the power of the images resulting from solitary, remote voyages derives from, and is precisely affirmed by, this lived alliance.

Given the double singularity of a certain existential stance and the aesthetic effects it authorises, is the object these images stand for, finally, actually, what we think? As he strides along, lens tilted upward, or as his finger presses the shutter, is Eric Bourret simply photographing the sky, as might have been supposed at the outset? What if he were showing something that the banal signifier sky, by itself, could not readily constitute? What if, in the end, his images were showing something other than this “thing” above the walker’s head? To ask the question, and to hazard an answer, means having to be patient, having to start looking a little more closely. A little more, in sum. A little longer, hoping that, gradually, contemplation may perhaps evoke something other than a generic reality: that of the sky, that of the skies. Or the heavens. And even, perhaps, in spite of their theological trappings. If we are to avoid forcing these images into excessively general categories, we need to revisit, for a moment, what characterises the experience of the photographer-walker, which involves the “altitude pedestrian”, as he tends to describe the kind of human being he turns into for several months each year.

As always, what really counts is the circumstances, the conditions, the material causes of the action; and in this case, above all, the set of empirical determinations of the adventure itself. If we want to grasp the sense of this artistic leaning, there are three points that need to be made. To begin with, these photos were taken at between 4,000 and 5,000 m above sea level, in Ladakh or Zanskar, not far from the Chinese and Pakistani borders. An extreme “elsewhere”, so to speak, marked by rarefaction (that of air, of life, of all those inert things that nonetheless combine to make a world) and extreme condensation (that of the light, the broad planes of silent matter transfixed by the cold, the sun, lacerated by dizzying peaks and crests). Photos from, as they say, the “roof of the world”. Then there is the fact that, whatever their immediate appearance, the photos were all taken either in the morning or the afternoon. In spite of the darkness that confers on them an astonishing, paradoxical beauty, these skies, though deep and sombre, are diurnal. And, last but not least, Bourret insists on the fact that they were taken while walking; so that on the one hand, it was on the move that the “motif” occurred to him, inviting framing and capture, always here and now; and on the other hand, if the value of the images is to be gauged, it must be recognised that they owe everything to the surprise of an exteriority exposed to a precise moment perceived as a marker of experienced duration, consciousness in movement.

Much has been said about what the act of walking permits, and what, precisely, it initiates. We know how this natural, or, we might say, elementary act, performed by the bipedal animals we are, sometimes has effects on another act which is much less so in us, namely that of thinking, as induced, precisely, by the tread of the resolute walker. It suggests a spiritual exercise with no aim other than the effect it produces on itself, i.e. on the walker who is devoted to it. Which naturally brings to mind Rousseau, or Nietzsche, or again, Thoreau. And closer to our own day, we might recall a meditation by the alpinist-philosopher Henri Maldiney, in which he discusses, and justifies, Nietzsche’s “Wanderer”, who says: “I am a wanderer and mountain-climber […] And whatever may still overtake me as fate and experience – a wandering will be therein, and a mountain-climbing”. And even if one went no further than that, it would be easy to situate Eric Bourret’s activity and work within this lineage; the more so as he himself identifies with the spiritual ascesis implied by walking in the mountains for the sake of the difficulty itself, if not the harshness. But the originality of the research revealed by his photographs, coming one after another and arranged according to subtle serial laws, invites one to go deeper, given that an unexpected question arises, deploying in secrecy. It is nowhere asked, of course, since photography is in essence mute. But one cannot help seeing in it what might be called the background noise of walking; something like the “basso continuo” of the itinerant photographer; or, perhaps, his dread. We might attempt to formulate it; but to do so without offending or betraying the insight that conveys it would require care, an absence of false shame, a certain naivety. Asking, for example: “Where does the sky start?”

If the question’s insistent, and if (as is being posited here) there’s a possibility that it summarises, in its own way, one of the issues involved in Bourret’s work, this is because it seems, however stealthily, to sustain his images. It acts, literally, as a motive to act. And the question “Where does the sky start?” is one which, if it is to receive a hypothetical answer, demands that we arise without delay, go along and see, get on the road and take, among others, the steepest path, which will become the vector of a slow, patient ascent. Provocative, but well-founded since the time when the idea of sky quit what the Greeks saw as the “sphere of fixed things”, this question opens onto the infinite. Its foundation, no sooner reiterated than denied, is a surface that is provisory, derisory and yet decisive (in that it determines nothing less than the here-and-now to which we owe our being). The surface referred to is the soles of our feet, resting, if only momentarily, on the Earth. Without warning, this type of question constitutes a step, a pace.

It has been said of Eric Bourret that he is a walker-photographer (and vice versa), and it should be pointed out that during his expeditions he covers between 20 and 30 kilometres a day, in conditions whose severity can well be imagined. This quickly produces profound effects, and perhaps even a metamorphosis, especially in the way one perceives and thinks about one’s relationship to reality. And Bourret feels, knows, seeks out, analyses, takes advantage of these effects. Over time, physical effort and lack of oxygen become favourable conditions for a mode of thinking that’s not just unthinkable in any other context but also singularly productive. Step by step, carried along by these effects, and advancing with the tranquil obstinacy of the investigator, the photographer-walker claims the ridges. And there’s nothing anodyne in this. Such zones are precisely those in which one’s relationship to the Earth is at its most restricted, its most tenuous. They are places where this inherently incoherent relationship almost ceases to exist, and which, once reached, are unusual in making the sky seem (so to speak) close at hand, as though changing into a reachable reality, were it not for the eternally intangible character of that which the word “sky” indicates. In a way, Bourret’s photographs bear witness both to this quest, this illusion that implies believing oneself capable of approaching the unapproachable, and at the same time overturning it. Asking oneself “Where does the sky start?” is, in truth, as necessary as it is rhetorical, never the antechamber of a conviction. Unless you believe in the existence of skies, you can’t reach the sky. And unless you consent to mere innocence, as the obverse of a consoling promise, you’re well aware you’ll never get there. The sky starts nowhere. It has neither commencement nor termination. Excessive action alone is to be seen in it. The sky yields itself up for what it is – a figure of the infinite.

It remains the case that there’s something to be seen, up there, above our heads. Neither a “being”, strictly speaking, nor a “nothingness”, but a positive void. For Pascal it was fearful, because of its silence, but also, as Rilke said, “full of attention”, because within it “the earth recounts”. And on this latter condition, sky is no longer the name of any given reality, but that of an opportunity for thought when, right before our eyes, a plot of a metaphysical nature is hatched. Which, in the end, is what Eric Bourret’s photographs manifest. And they do so in magisterial fashion. But this isn’t all they manifest. The clearly proclaimed chromatic delicacy of the nebulosities, along with the surprising, discreet values of ochre and blue that give the blackness a subtle density, and the motif of a vibration that verges on the imperceptible – these are indications that the sky doesn’t exist as such, except as the enduring image of that which neither begins nor ends, but vibrates, is made and unmade, and by the same token exhorts existence to go beyond stasis, to finally get moving, and to go, precisely, to where nothing would have summoned it, other than the summons itself. Proceeding from ascesis, words and ideas orientate the eyes of those who dare, and who launch out, bodies and minds heading for a possible renaissance through an interim loss of self. Notwithstanding what strikes us at the outset, and as habitually keen as we are not to see, it must now, no doubt, be agreed that Eric Bourret has perhaps never photographed anything at all of the sky. But this “never” is consistent, to the point of requiring the scrupulous updating of an indefinite series so that the dialectic of the singular and the plural can come about. Which means returning, again and again, to this place that’s not really a place, standing on the uncertain boundary of the Earth that’s marked by the ridge; where suddenly one’s up there in the sky; where, without a word, something, finally, is “recounted”. [Text by Pierre Parlant]

About Éric Bourret

Born in 1964 in Paris, Éric Bourret lives and works in the South of France and in the Himalayas. His work as an “artist-walker” participates in the tradition of Land Art and land surveying photography. Since the early 1990s, he has been traveling the world on foot, hiking over all kinds of terrains and at all altitudes, shooting photographs that he refers to as “experiences of walking, experiences of the visible.” His photographs evidence the deep physical and sensory transformations that the act of walking over long distances triggers, as it heightens perception and receptiveness to the surrounding landscape.

During his walks, which last a few days to several months, the artist superimposes different views of the same landscape on a single negative according to a precise conceptual protocol that stipulates the number of shots and the interval between them. These sequences intensify and accelerate the imperceptible movement of geological strata and freeze the ephemeral temporality of human beings. The accident and the unexpected are integral to this concept of random photographic shots. This photographic ephemeris breaks down the structure of the initial image and creates a different sensitive, shifting reality. The image born of this “temporal layering” is vibrant, oscillating, practically animated. More factual series include date, place, duration, distance travelled and thus convey the rhythm and the space of this walking log (carnet de marche).

Éric Bourret’s images can be seen as photographic notes in a surveyor’s score. They attest to a subjective experience, as he himself has admitted: “The landscapes that I travel through and that travel through me constitute me. I see the photographic image is a receptacle of forms, energy and meaning”. Since 1990 his work has been the subject of many exhibitions and has entered the collections of numerous museums and art centres in Europe, North and South America and Africa, including notably the Finnish Museum of Photography in Helsinki; the Museum of Contemporary Art of Tamaulipas in Mexico; the Musée d’Art moderne et d’Art contemporain in Nice; the Musée Picasso in Antibes; the Maison européenne de la photographie in Paris. In 2015-16, he participated in several group expositions: Paris-Photo; Dallas Art Fair; Seattle Art Fair; Joburg Contemporary African Art; AKAA in Paris; the Venice Biennale; and Start at the Saatchi Gallery in London. [Official Website]