Anni Albers reflected that all weaving traces back to “the event of a thread.”

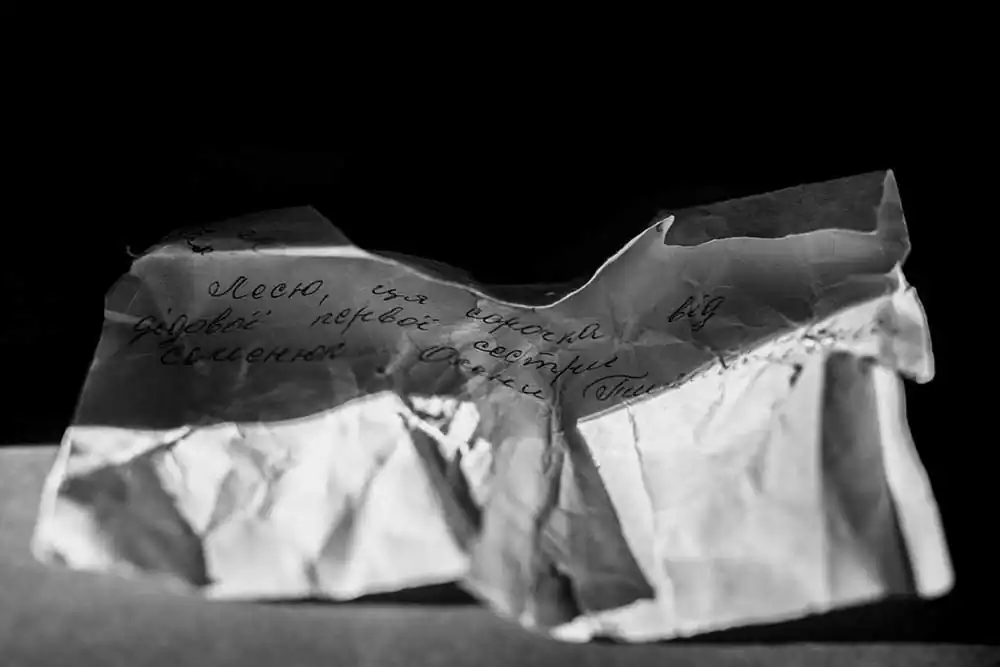

Maruschak is a descendant of immigrants who came to Canada from Ukraine in 1897 wearing vyshyvanka – Ukrainian for embroidered garment. Almost 90 years later, she visited her ancestral homeland and returned to Canada with a vyshyvanka and a humble handwritten note. The garment hung in the dark, protected from the light for decades – its story as hidden as it was.

WO·MAN: Place points to a symbolic experience. Maruschak was captivated by the garment’s apparent beauty; yet, its materiality – frayed edges, bleeding dyes, and yellowing fabric – spoke to her of memory making, ritual and place. The weaving process, the bespoke pattern, and the hand-stitched seams drew her in. This artefact had a language of its own where different forces were stitched and woven together, where diverse skills, experiences and knowledge were combined. The garment spoke of community. The tension inherent in this experience is an echo that prevails throughout, as is the role of the photograph in provoking an inquiry by the viewer.

A black-robed incarnation of destiny – the keystone of WO·MAN – appears in Maruschak’s work for the first time. She represents the mother thread of life – the fragility of human experience. In these self-portraits Maruschak conceals her face, and denies the viewer the validation of identity – she could be any woman. Yet, she is connected to the symbolic items as she holds them in the performance and bears witness to her presence entangling the story in the present tense.

The palette, contrasting between muted minimal tones and the bright red of the vyshyvanka, and the inclusion of found items convey a narrative that touches upon memory as a personal and corporate thing. Curator for our journey, she straddles the present and past speaking to the power of tradition and ritual in a contemporary manner.

WO·MAN: Place spurs an exploration of reinvention, shifting identity, and cultural issues of global significance as we make our way through contemporary debates on immigration.

MAKING MEMORY

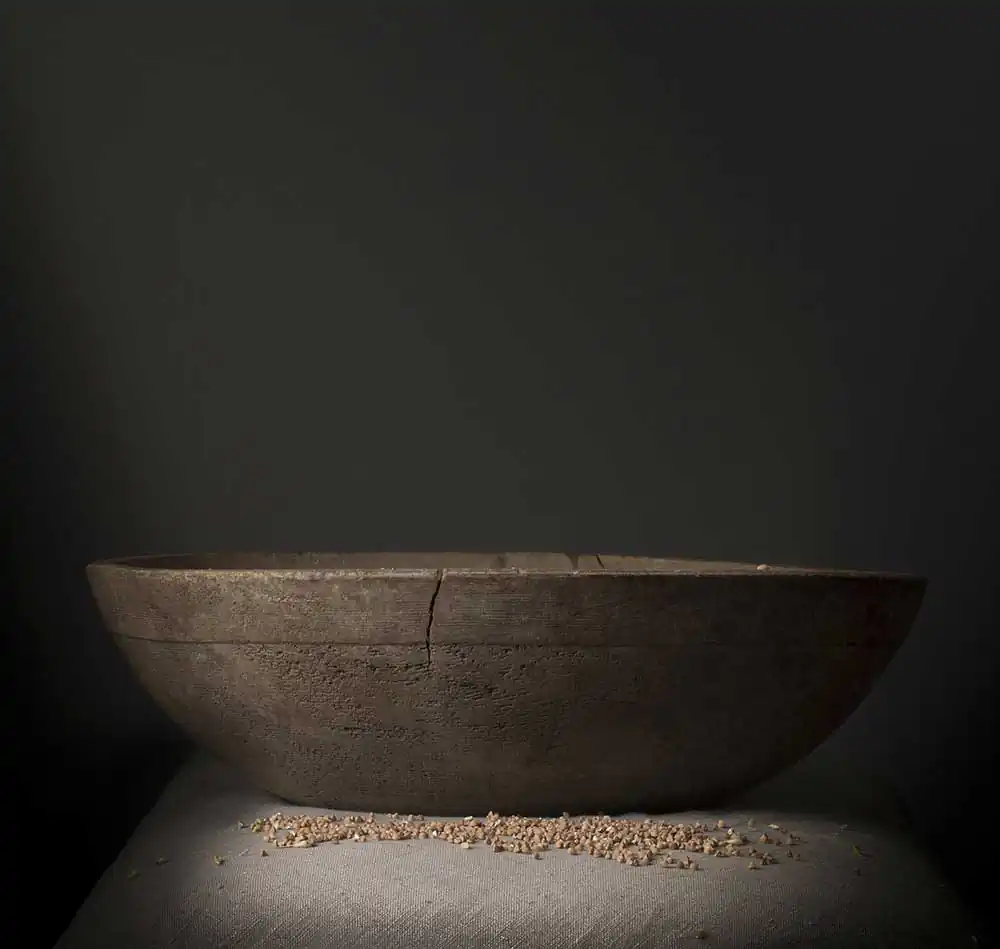

At the center of WO·MAN lies a vyshyvanka, the iconic Ukrainian garment that was gifted to Lesia Maruschak by her great aunt over thirty years ago. A string of images explores the various surfaces of this garment – an expanse of unadorned white cloth, the hidden seams of the lining, and the famously intricate embroidery with its bold geometric patterns partially obscured by a thin veil of sheer fabric or by a folded sleeve.

These images trace the artist’s ritual handling of cloth, flipping the garment back-to-front, turning it inside out, searching for holes, examining its construction, feeling its weight and texture in her hands. They create the sense of an active memory; not simply acts of remembering a lost relative, but the act of memory-making through touch and gesture, through an embodied relation with the material. By physically exploring and visually foregrounding the materiality of the vyshyvanka, Maruschak merges personal and political histories to create collective memories.

Holes trace the garment’s lineage of ownership and legacy of use within the artist’s family, but also mark the passing of hands and the crossing of borders, signifying larger waves of Ukrainian migration. Stitches similarly map the handiwork of the WO·MAN who made the vyshyvanka, but also recall eras in which embroidery occupied a liminal space in gendered economies, as a tool of patriarchal oppression and resistance, of female subjugation and feminist agency. By revealing the entirety of the garment – its seams and inner lining as well as its decorative patterns – Maruschak exposes female labour as skilled and meticulous in a feminist gesture that beckons viewers to critically consider the paradox of craft.

Maruschak’s photographs of the vyshyvanka constitute a performative memory-making, and by enveloping the camera in the fold of the fabric, Maruschak extends this performativity to viewer, inviting us to make memories of migration and distant homelands, of economy and exchange, of labour and power. Memories – especially collective memories – are not something we have, they are something we do. [Text by Pamela Grombacher] [Official Website]