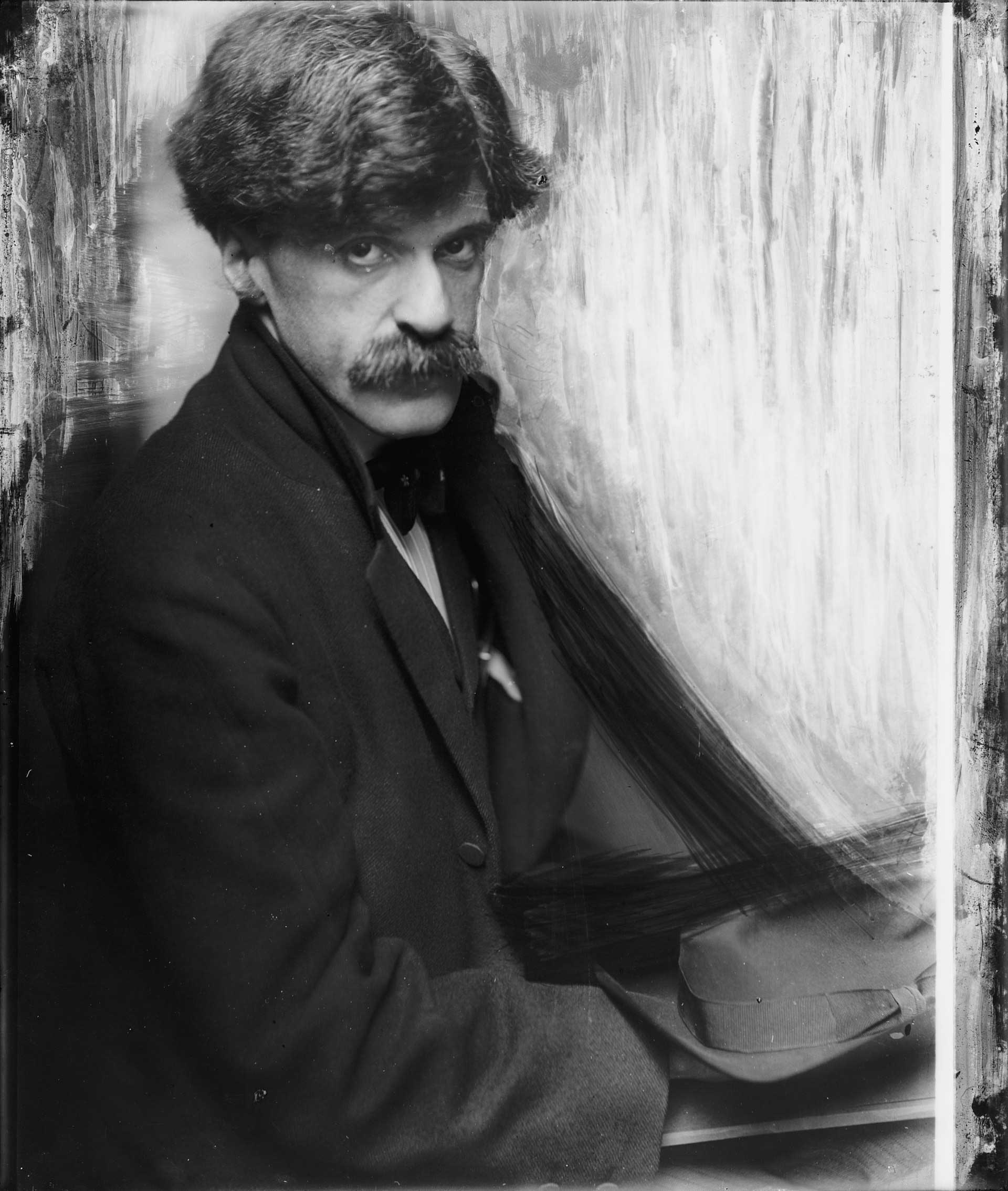

“Behind All of Us Stands Stieglitz”. He is one of the key personalities in the history of photography. Photographer, publisher, theorist and critic, Alfred Stieglitz was one of the main proponents of the dissemination of the new avant-garde currents and the recognition of photography as art.

Impeller of the arts, there were many European artists who exhibited for the first time in America thanks to his initiative. Alfred was also the axis of the generation of American artists today known as the Stieglitz group.

Alfred Stieglitz was born on 1st January 1864 in Hoboken, near New York, during the American Civil War. He grew up in a Jewish family of German origin, very well integrated into the American society.

He was the eldest of 6 brothers and emigrated to Germany in 1881. After moving with his family, Alfred studied mechanical engineering at the University of Berlin and began taking his first photographs around Europe. He enrolled in chemistry classes taught by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, one of the great discoverers of advances in the field of photography.

There are many schools of painting. Why should there not be many schools of photographic art? There is hardly a right and a wrong in these matters, but there is truth, and that should form the basis of all works of art

In Germany, he has the opportunity to get in touch with the debates that animated the European photographic circles. He not only toured Germany, but also Italy and the Netherlands, and, apparently, he took advantage of all the opportunities presented to him to portray the peasants he encountered, and also to practice landscape photography.

Stieglitz fought to make photography an art form at the level of painting and sculpture. To achieve this objective, he began exploring in the field of photography his own abilities in painting (composition, textures …) and then resorting to photographic elements (depth of field, photographic cutting effect …). He went from pictorialism to the so-called direct or realistic photography.

In 1890, when he returned to New York, he created the ‘Photochrome Engraving Company’ (a photoengraving press) with other partners and bought his first “portable” camera, a 4 x 5” Folmer & Schwing Speed Graphic. He also began working as an associate editor of ‘The American Amateur Photographer’ magazine.

In 1902 he organized a group that could only be entered by strict invitation, and called it Photo-Secession, in order for the art world to discover the recognition of photography as a distinctive means of individual expression. The members of the group included Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, and Alvin Langdon Coburn. In Spain, the work of José Ortiz Echagüe stands out. He also opened his first galleries around that year, where photographers heavily influenced by European pictorialists were exhibited.

Let me here call attention to one of the most universally popular mistakes that have to do with photography – that of classing supposedly excellent work as professional, and using the term amateur to convey the idea of immature productions and to excuse atrociously poor photographs. As a matter of fact nearly all the greatest work is being, and has always been done, by those who are following photography for the love of it, and not merely for financial reasons. As the name implies, an amateur is one who works for love; and viewed in this light the incorrectness of the popular classification is readily apparent.

In 1903, after noting that the reception of the secessionist group was very good, he immediately encouraged himself to launch ‘Camera Work’, a new photography magazine in which he could give free rein to the pictoralist vision that he practiced and defended.

The term “Straight Photography” is coined in a Camera Work edition of 1904. In an article written by the critic Sadakichi Hartmann, on the occasion of a photographic exhibition, he convinces photographers to produce images instead of paintings and uses the expression “to work straight”, to work directly. Somehow it constitutes a rejection of pictorialism, the touch-ups and manipulations so frequent until then.

Initially, alongside the desire to be accredited as an art, photography on ‘Camera Work’ was proposed as a privileged means of capturing the fast-growing modern world in a lightning-fast way, in a readiness of vision that no other medium possessed.

In 1905, assisted by his friend Edward Steichen, he rents a studio on Fifth Avenue 291 in order to exhibit the works of the photo-secessionists. The gallery takes the name of “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession”, later known simply as “Gallery 291”, becoming a point of reference for modern art in the United States.

It is not art in the professionalized sense about which I care, but that which is created sacredly, as a result of a deep inner experience, with all of oneself, and that becomes ‘art’ in time.

Camera Work, thanks to the recommendations of Steichen, Stieglitz’s trusted ambassador to Europe, managed to publish works by Rodin, Matisse, Picasso, the writings of George Bernard Shaw (among many others), becoming a place of discussion on theoretical-methodological questions of art.

In 1910, he was invited to hold an exhibition in Buffalo, New York; in the Albright Art Gallery that reached visitor records. During the 30’s, he also presided over two non-commercial galleries in New York, “An American Place” and “The Intimate Gallery”.

In 1937 his illness forced him to abandon his work on the street, and the last ten years of his life were spent in Lake George in New York, during the summers and with his second wife, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe, in the Shelton of Manhattan, which would be the first skyscraper in the New York neighborhood.

He died on July 13, 1946, at 82 years old.