The people of 13 de Noviembre have experienced hardships, ostracism and disaster – but is change on the horizon?

13th November 1985 was Colombia’s worst natural disaster. The volcano Nevado del Ruiz erupted near the towns of Armero, Chinchiná and Villamaría, killing around 23,000 people.

13 de Noviembre, named in memoriam of those that perished that tragic day in 1985, is also a barrio on the eastern border of the valleyed Colombian city of Medellin.

13 de Noviembre was originally an illegal settlement of refugees. It was given no governmental assistance for a number of years and was built with very little oversight. Since then, however, there has been a strong push by EPM, the state-owned water and energy provider to bring both into homes. However, even now 15% of the houses do not have running water or electricity.

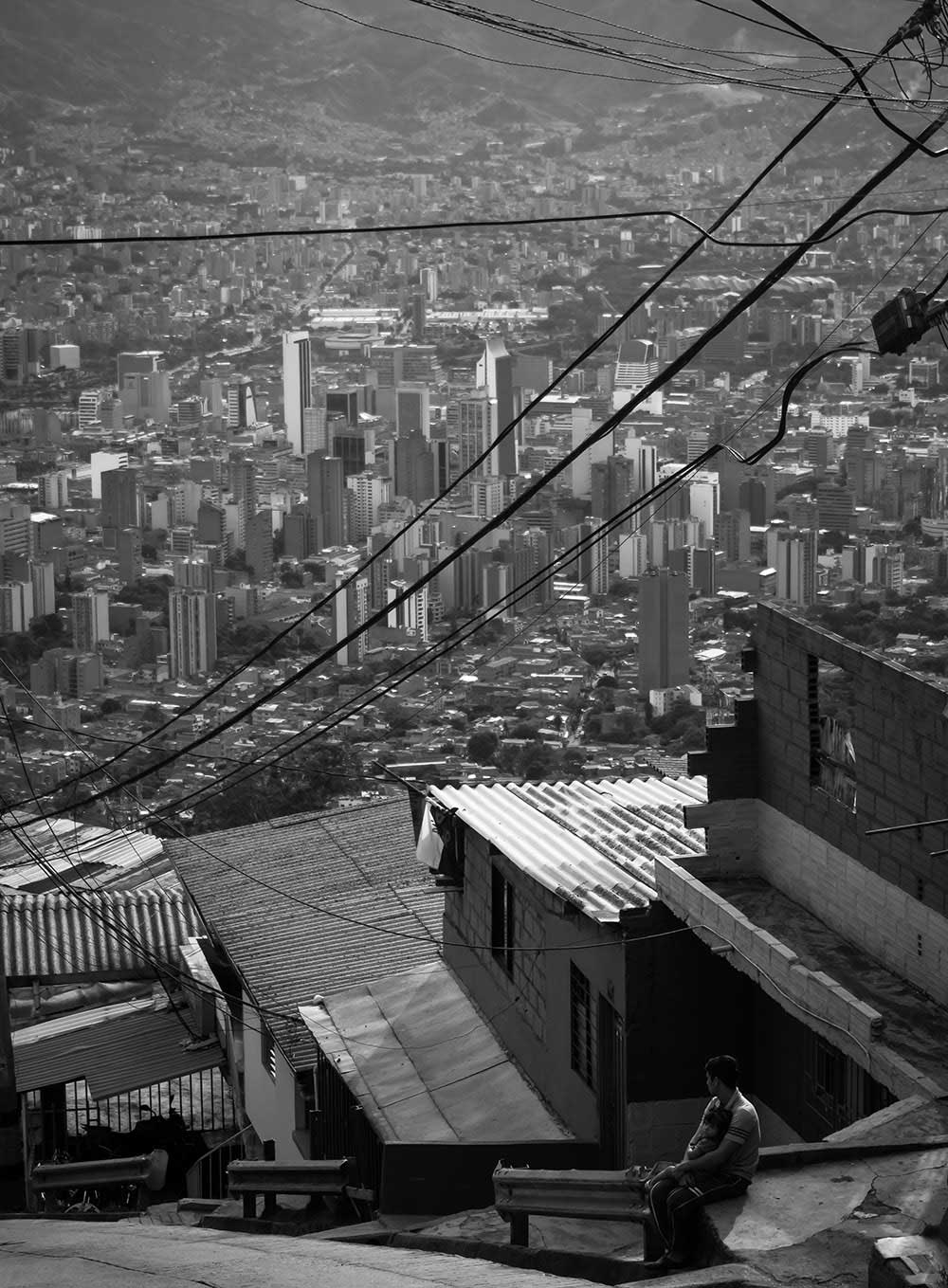

Drunk on altitude and sitting giddy at a lofty height of nearly 1800m, the residents quite literally look down over the rest of the city. It is perched calamitously atop Comuna 8’s almost impossibly steep hills where the roads only go so far and even the most basic items have to be carried up — it truly is back-breaking work.

Until very recently Colombia had the highest number of displaced people on earth due to a combination of civil war, military and paramilitary groups driving people out of the countryside, drug-cartels appropriating land and natural disasters. Even now, it is only second to Syria. This issue has forced itself back into the spotlight recently because of the country’s failed peace referendum earlier this month. The United Nation’s High Commissioner called this tragedy Colombia’s “Invisible Crisis” due to the fact that the vast majority of people displaced are within their homeland. There are an estimated 5.7 million people displaced within Colombia.

The neighbourhood itself is formed of bric-a-brac housing and with largely corrugated iron roofs, and in some ways still has a very temporary feel to it. Mentioning the barrio to wealthier Colombians tends to draw mouth-covered gasps of “¡Cuídate!” — [Take care!]. Clearly, 13 de Noviembre has had a chequered past, but that is a far cry from my own experience. Mine is of being welcomed into people’s homes, children playing in the street, bars blaring out salsa at top volume and torrents of jokes being thrown from all angles. Walking past a tiendita selling empanadas, I hear the man on the left howling with laughter after saying, “¡Eh, cómo canta, el hijueputa!” to a young boy, which loosely translates as “Eh, the little motherfucker can sing!”

The way that I see it, 13 de Noviembre is a testament as to what can be done with little funding, basic materials and a community that helps one another, and should be recognised as such.

One thing I often forget, coming from a secular background, is how much of a role religion plays in people’s lives here. Speaking to a number of locals, I asked what the best thing that had ever happened to them. The overwhelming response was either “Christ” or “God. I visited a church, La Iglesia Movimiento Misionero Mundial, near the top of the mountain and experienced the passionate service first-hand. The sermons were every bit as fire and brimstone-esque as the God of the Old Testament.

For a time around 1990-1993, just before the death of Pablo Escobar, Medellín was the most dangerous city in the world. More than 6000 people were murdered annually. Drive-by shootings and bombings were frequent and indiscriminate. Governance had been lost in the city. The need for radical reform was urgent.

One of the masterminds behind the change was Mayor Fajardo, a maths professor who had no political experience before becoming mayor in 2003. He recognised that there was an economic and social divide between the more affluent parts of the city and the comunas that sprawled up the hills around it, but more importantly there was a geographical divide. The separate parts of the city stayed separate, there was no intermingling within the different classes. Fajardo realised that the situation could not possibly be solved by policy measures alone, but rather the solution would be achieved through urban design.

The authorities went about reorganising the fabric of the city by transforming Medellín’s public spaces into inclusive areas where people could come together, and, more vitally, integrating mobility systems. They planned a series of metros, bus lanes, cable cars, bridges, and even escalators that would eventually stitch the city together. Importantly Fajardo used workers from those areas he wanted to link to build the new infrastructure. This even meant dealing with criminal gangs to achieve his goal.

The project has been a phenomenal success and now even those in the furthest and most remote places in the city can travel to polar opposite sides of the city with ease and on a single fare. It has been such a triumph that Medellín this year was taken off the list of the World’s Most Dangerous Cities, having been deemed too safe to be judged as such. Less dangerous than St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit and New Orleans in the U.S.A.

Currently, the only public form of transportation connecting 13 de Noviembre and the rest of the city is a bus that runs into the centre of the city. Winding up and down perilously precipitous and narrow streets, it transports thousands of residents to and from home and work. Finally, the cable-car line that is due to connect 13 de Noviembre to the rest of the city, will open later this year. With the ability to transport 1,800 people an hour, it will bring much needed economy to an area so long neglected.