As one of the leading photographers of the 20th Century, Irving Penn’s modernist approach aligned with the birth of modern minimalism, which in 1960s New York, provided a counter to the busyness of abstract expressionism and consumerism dominating the post-war years.

He was well-known for his clear and unobtrusive style of composition, with its meticulous organization and attention to detail.

Born to Russian Jewish parents in Plainsfield New Jersey, Penn went on to study at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, where he created drawings for Harper’s Bazaar under the supervision of Alexey Brodovitch. Following three years of freelance work and a year working as art director for Saks Fifth Avenue, in 1940 Penn was offered the position of associate for the magazine art department at American Vogue.

This role formed the majority of Penn’s career (60 of his 70 working years), during which he created images that caught the public’s imagination, including a dripping faucet with three pear diamonds provided by diamond dealer Harry Winston and a 1963 magazine cover featuring a grid of seemingly-random images reminiscent of a surreal cabinet of curiosities.

Making the Ordinary Extraordinary

Penn’s still-life work, with its ability to capture everyday objects in fresh, original ways continued into the 1960s and 1970s, with Penn photographing all manner of ordinarily-ordinary objects from fall leaves to coffee cups – unusual, yet not so very strange considering Penn was once quoted as saying that even “photographing a cake” counted as art.

This approach could also be applied to Penn’s work with a diverse range of equally ordinary people ranging from Hell’s Angels to small trades representatives in Paris, London and New York, a collection including butchers, bakers and a pest controller dramatically brandishing a spray pump. Although posed, the images had an air of informality, each capturing the personality of Penn’s subjects in a style that would eventually be emulated by the street style blogs of the 2000s.

Penn in the Studio

Examples of location photography in Penn’s work are rare: the restrained, deliberate style of his work lent itself to the confines of a studio, where he could edit out anything superfluous to the composition. Monochrome backdrops highlighted the visual clarity of Penn’s work, enabling him to have greater control of the available natural light.

Despite the refined nature of Penn’s work, he was also influenced by the innovative, rebellious nature of artists. This particular use of lighting was a departure from the trend for using artificial lighting, distinguishing Penn from other photographers of the period.

Up Close and Personal

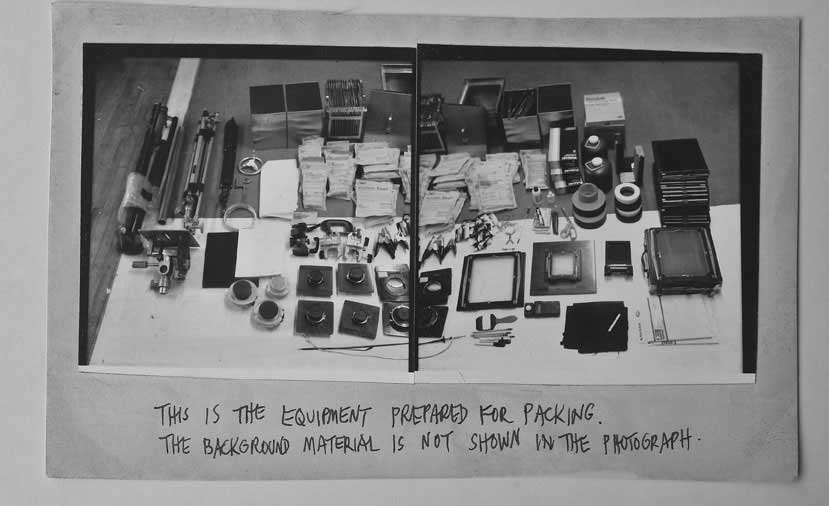

Between 1964 and 1971, Penn traveled to Morocco, New Guinea, Cameroon, Nepal, Dahomey, Spain, Japan and Crete. Wherever he went, he took his talent for capturing the personality of his subjects, creating portrait photographs of local people in natural light, but rather than shoot outside, Penn constructed a portable studio using a tent he could take from place to place.

Other, earlier works by Penn include a collection of nudes entitled Earthly Bodies, featuring images captured between 1949 and 1950 that were considered risqué for the time. Inspired by historical art, Penn sought to “break through the slickness” of professional photography, creating a softer, more personal portrayal of the human form.

Penn’s close-ups of celebrities are equally intimate and entirely different from images seen on billboards and the red carpet: Isabella Rosselini, looking dreamy and winsome; Miles Davis tenderly clutching a trumpet to his chest, as though soothing a child. The images of familiar faces (frequently shot without any retouching) not only reveal physical flaws, but also a truth that bears repeating: that beneath the glamor of celebrity, our cultural icons really are just like us.

Family Life

In the 1950s, Penn founded a studio of his own in New York, creating advertisements for brands such as Clinique, Issey Myake and De Beers. Around this time, he met his wife, Swedish model and artist Lisa Fonssagrives in Paris, a meeting described by Penn as love at first sight. Two years after their wedding, the couple had a son, Tom (who would later go on to become a metal designer). Hardworking and reticent, what little time Penn spent not working was spent with his family.

Following Fonssagrives-Penn’s death in 1992, Penn retreated to the sanctuary of his studio, where he used the space to paint, an ambition he had harbored since his postgraduate years. In 2005, four years prior to his death in New York at the age of 92, Penn launched the Irving Penn Foundation to preserve and promote his work; a legacy that has continued to inspire photographers around the world.

The poet Charles Baudelaire once said that in order to be “violent and original” in one’s creative work, it was first important to be “orderly”. It’s a precept that could easily be used to describe the work of Irving Penn, a photographer who built an innovative, yet timeless body of work on a scaffold of quiet discipline and diligence.