Stark and rugged in her beauty, an intricate mosaic of empty canyons and dry riverbeds, streaching from desolate Skeleton Coast to arid landscapes of Kokoland and towering dunes of an ancient Susuvlei desert.

Namibia, home to many religions, languages and cultures, which have found a way to thrive in this unique environment living according to the traditions of their ancestors.

Around 16th century Himba people crossed to Namibia from Angola, settling in Kaokoland (nowadays Kunene) as part of Herero tribe. Few centuries later, bovine epidemic swiped through Namibia, causing Herero a great loss in cattle. Facing great crisis, the tribe decided to move south, exploring different regions in order to enhance their chance of survival. Still, despite famine and hunger, some members decided to stay and struggle for survival in familiar territories, asking other tribes for help in searching for cattle or crops. Impoverished by disease amd Nama cattle raiders, Himba were left without live-stock, forced to rely on land for their survival. Driven by hunger, many Himba fled to Angola, where they were called Ova-himba, meaning ‘beggars’ in Otjiherero language.

People of the Earth

Himba, like most indigenous people, live on what nature provides for them, their diet consisting of mostly of porridge, meat being reserved only for special celebrations. Like many other tribes living in the area, their survival depends on cows and as a result, a Himba man without a herd of bovine companions isn’t considered worthy of respect. When the pasture’s offerings disappear, tribe will travel to a new location, where their livestock can once again eat to their fill. Himba homes are simple huts, made from a mixture of earth and cattle dung and contain little beyond a bed and collection of useful implements such as kitchen tools. Both woman and men wear their traditional dress, loin cloths and sandals for a man, often with foot soles made from old car tires, goat skinned skirts and jewellery for women.

Love and marriage

Himba people practice polygamy, with both men and women being allowed to have multiple partners as long as the arrangement is open and agreeable by all parties involved. Men tend to have several wives, especially if they are rich in cattle, as the animals’ ownership is passed down from mother to daughter. The more cattle a woman owns, the greater her status and that of her family. Marriage is important in Himba culture, but extramarital relations are encouraged by families. When their husbands are away with the livestock, it is common for the women who stay behind to have “affairs” with other men.

Egalitarian in their social structure, all tribe members enjoying full equality of rights, decisions being split between men and women, with an overall authority in the hands of the men but economic issues decided by the women. With clear division of roles, women have the job of tending to children and livestock, which is led by men the to pasture for the day.

Between the two words

Himba are animists and their supreme being is called Mukuru, a holy fire (okuruwo) is the way to communicate with their God. The fire, is kept continuously alight, a bridge between the living and the dead, the line of communication between the village chief and the ancestors, who stand in direct contact with the Supreme Being. All houses’ doorways face away from the holy fire, with the exception of the chief’s house, which allows its sacred glow to light his domain both day and night, assuring his link to the other side is never interrupted. The holy line starts from the main entrance of the chief’s hut and goes straight, passing the holy fire, to the entrance of the cattle enclosure. Holy Fire is kept alive until the death of the headman. When this happens, his hut is destroyed and his “holy fire” and left to slowly burn down to only embers. His family will dance all night in mourning.

Only those, who are invited are allowed to cross the holy line and sit by the fire to share their stories and laughter with tribe over food and drinks. Oftentimes, the chief can be found, aglow in the fire’s light, holding communion with tribal ancestors, asking for a blessing and guidance. Each night, before the Himba people retire, an ember from the sacred fire is carried, into the chief’s house, in the morning, chief will use same ember to reignite the sacred fire weakened by the night’s wind.

Iconic red woman

Washing the body with water is not only a luxury, it is considered wastage, and is strictly prohibited, so, instead of bathing, women apply the otjize paste every morning in a grooming ritual that can take two to three hours. The mixture is a beautiful, scented with aromatic resins, deep in orange colour symbolizing the earth’s red colour and blood—the essence of life. Otjize is considered the ideal of Himba beauty, also offering protection from the sun and insect bites. The red ochre cream is made by pounding the ochre stone (Hematite) into small pieces. Thereafter the fragments are mixed with butter, slightly heated by means of smoke and applied on the skin. The red layer seems to help against the scorching sun radiation, while keeping the skin clean and moist and to some extent it blocks hair growth on the body.

Apart from applying red ochre on their skin, Himba women do take a daily smoke bath in order to maintain personal hygiene. They will put some smouldering charcoal into a little bowl of herbs and wood of the commiphora tree and wait for the smoke to ascend. Thereafter, they will bow over the smoking bowl and due to the heat they will start perspiring. For a full body wash they cover themselves with a blanket so that the smoke gets trapped underneath the fabric.

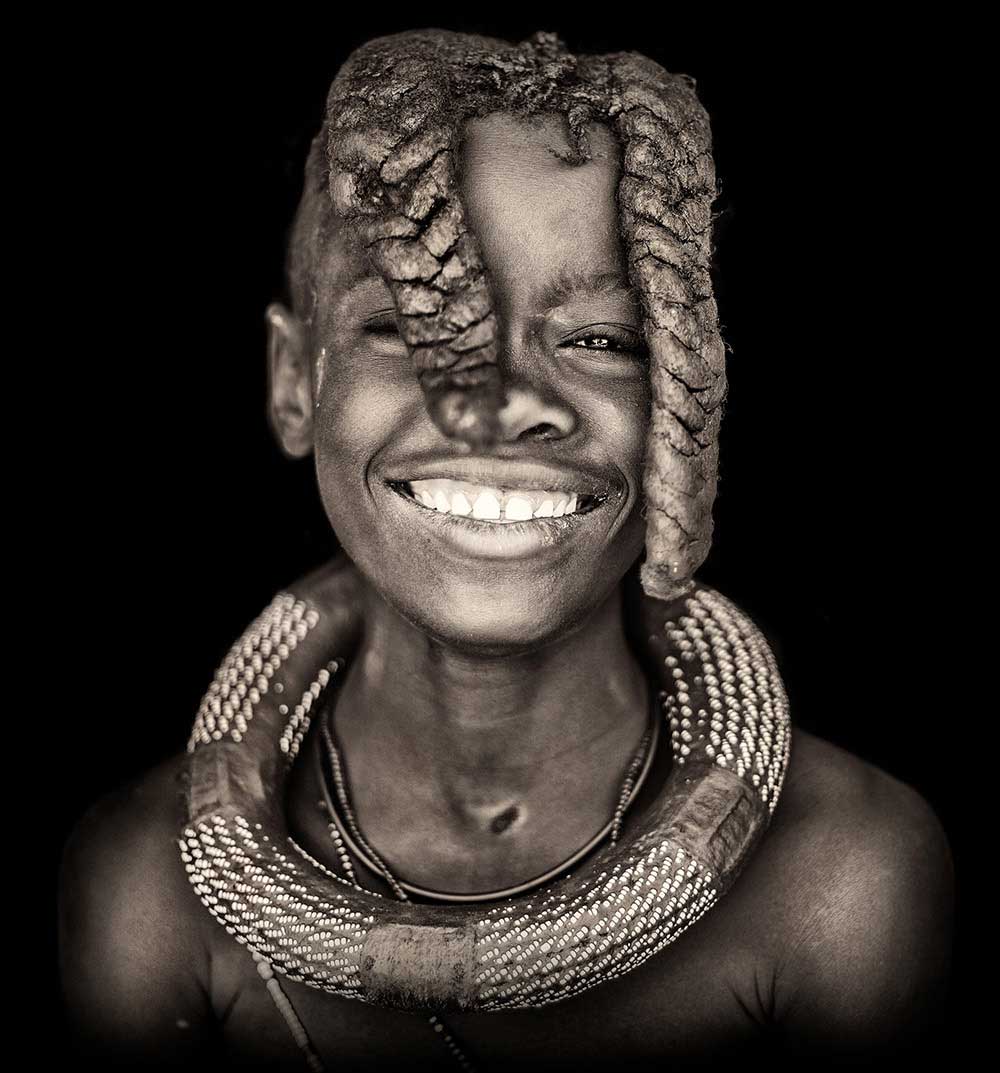

Crowned beauty

Proud and exquisite, Himba women are said to be one of the most beautiful in the world. Fiercely proud of their traditional hairstyles and clothes, taking several hours each morning for their beauty care and just like Geishas, they sleep on wooden pillows not to ruin the hair style in the night. Both men and women take great care they in wearing their traditional attire, clothes, hairstyle and jewellery are all of particular significance to the Himba, and are part of their tradition and culture.

The first beauty task is to take care of their dreadlocks, then women cover themselves completely with otjize, which acts as a sunscreen and insect repellent. The red colour is considered a sign of beauty, and otjize is smeared all over, including not only on their skin and hair but also their clothes and jewellery.

Women dress in goatskin skirts embellished with shells, iron, and copper jewellery, and striking, cattle-horn-like headgear, erembe, also donned by their relatives, the Herero. The Erembe crown is made of cow or goat leather and is placed on the girl’s head after she’s married for a year or has a child. Women wear a large white shell necklace called the ohumba, which is passed from mother to daughter. Equally popular, particularly among married women, are heavy necklaces made from copper or iron wire, much of which is taken from electric fencing, some wear keys and bullets as decoration as most of their houses don’t have locks. The adult Himba women all have beaded anklets called omohanga, where they hide their money, anklets also serve as a protection against venomous animal bites.

Goat hair and mud

From the time a Himba girl is born, her hairstyle will identify her place in society, indicating age, clan and marital status of a woman. The hair is first lengthened with straw woven together with hair extensions to create dreadlocks, which are then covered in otjize and finished with goat hair, added to give the distinct pom-pom look.

A young girl typically has two plaits of braided hair (ozondato), the form of which is decided by the clan (oruzo) she descended on her father’s side. A young girl who hasn’t reached puberty yet, will display two braids at the front of her head, if a girl is a twin, she will wear only one single braid, indicating she is only one half of a pair of twins.

At puberty, the girl will wear braids up front covering her face, letting males know that she isn’t ready to marry. When a young woman is ready to marry, same locks will be braided toward the back of the head, allowing potential suitors to see her face. When a woman has been married for a year or has had a child, she will wear the erembe headdress on top of her head.

Men, on the other hand, have very simple coifs. Single men wear an ondatu plait on the back of their head, married men cover their hair with turbans for the rest of their lives, only shaving their hair and removing their turbans during funerals.

The smallest children tend to have shaved heads, although, some might have special haircuts to indicate their clan. New-born babies are adorned with bead necklaces, bangles made of beaten copper and shells are added when the children are a little older. [Official Website]

One comment

serge janssens

Aug 16, 2017 at 10:40

Un bonheur subjuguer …

Comments are closed.