Dorothea Lange, A woman who decided to break the paradigms of an epoch in which photographers did not leave their studios. With the United States summed in the Great Depression, Dorothea Lange went to the streets to portray real life, and what she found was the suffering of the people: poverty, misery, unemployment and the homeless.

Born as Dorothea Nutzhorn in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1895. She studied at the Training School for Teachers in New York and photography at the Clarence White School in the same city. At age 7, she suffered from poliomyelitis, and due to the treatments of the time, she grew very weakened and with serious malformations in her feet. Devastating consequences for a child, but it wasn’t an impediment for her to fight for her goals and objectives.

She worked as an assistant in various photographic studios such as Scott-Beatty and Arnold Genthe in New York. In 1919, before she turned 24, she opened her own studio in San Francisco, where she met her first husband, Maynar Dixon (a painter). Her first approach to photography was with very different intentions to those she ended up developing over the years and the coming of the Wall Street crash.

In 1929, the New York Stock Exchange suddenly fell, beginning a stage of economic crisis that became known as the Great Depression. The 20’s came to an end to give way to a period of worldwide recession. In the United States, misery spread like a plague. Thousands of people were mired in total poverty. That’s when Dorothea, unlike the photographers of the time who did not abandon their studies, decides to go to the streets to capture with her camera the situation of thousands of American workers and peasants who had lost their jobs. Unknowingly, this would professionally reinvent her and forge her legacy.

Her images soon interested the United States Agricultural Security Administration that hired her to make a series of reports on rural poverty. These images showed a lot of humanity and sensitivity. They were images that came from social consciousness.

Between 1935 and 1937 Lange worked for official departments, always having as protagonists in her photos the poor and marginalized. She distributed the photos (free of charge) to national newspapers; photos that became icons of the era. During this period, she opened her second studio in Berkeley, California.

A year later (1938-1939), Lange prepares with her second husband, Paul Schuster Taylor, the book “An American Exodus, A Record of Human Erosion”, in which they combined photographs taken by her and texts in order to analyze the migratory phenomenon of agricultural workers. They also collected conversations on microfilms while the photographs were taken, becoming a pioneer book in combining images with oral testimonies for a contemporary audience; from its creation until today it is considered one of the masterpieces of the documentary genre.

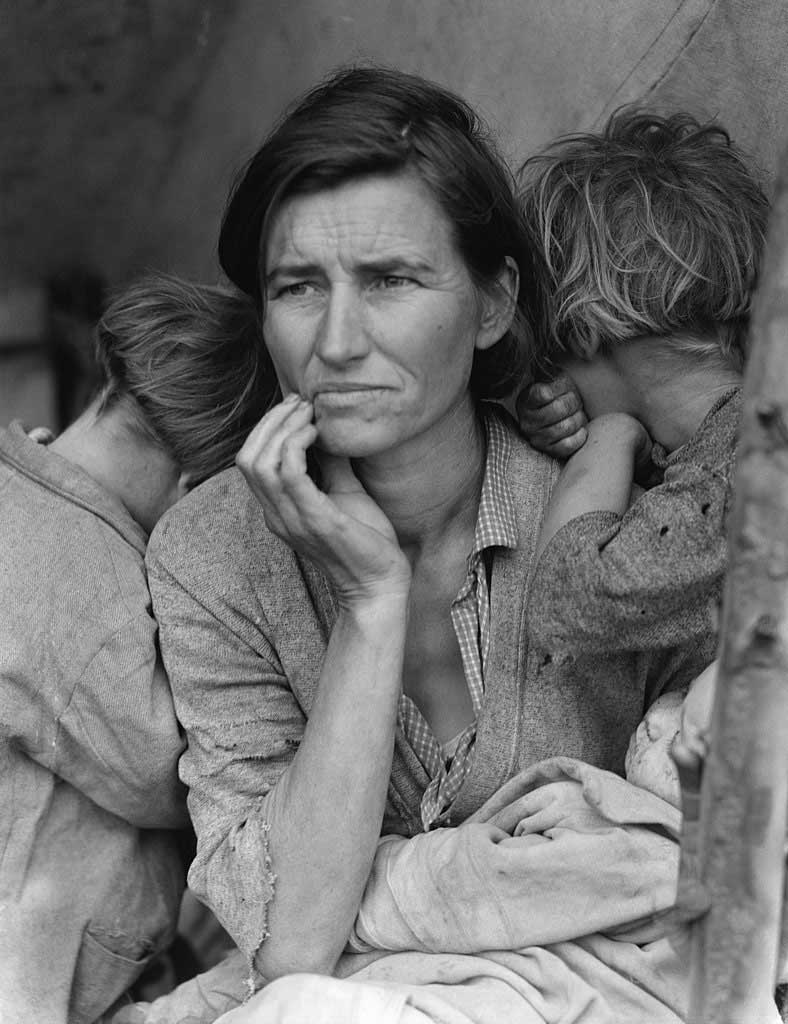

Among all the images Lange captured at this time, there is one that stands out among all: “Migrant Mother”. The photograph, taken in 1936 in California, portrays a 32 years old famished mother with three of her seven children. This photo became an icon of the history of the 20th century in the US, and thanks to it, Lange became a reference in photography and graphic documentary.

“I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.”

It is also quite known (now) her work on the internment camps of American citizens of Japanese origin, carried out in the later decade of the 40s, during the period of World War II, and which, at the time, was censored by the War Relocation Authority. A work that exposes the miseries and conspiracy paranoia of the elites of power of her country. Her photographs, witnesses to the unjust policies of detention of people without any criminal charge, and without the right to defend themselves, show us a really shameful moment for the US government, in which many girls and boys appear honoring the flag before being sent to concentration camps.

“I many times encountered courage, real courage. Undeniable courage. I’ve heard it said that that was the highest quality of the human animal. I encountered that many times, in unexpected places. And I have learned to recognize it when I see it.”

She was the first photographer to receive the Guggenheim scholarship in 1941. During the fifties, she collaborated with Life magazine, and during the next decade she worked as an independent photographer reporting from Asia, South America and the Middle East.

From 1964, after being diagnosed of cancer, she dedicated herself to what her last two projects would be: to organize a retrospective of her work at MOMA and to document her life. She died of cancer in San Francisco in 1965.