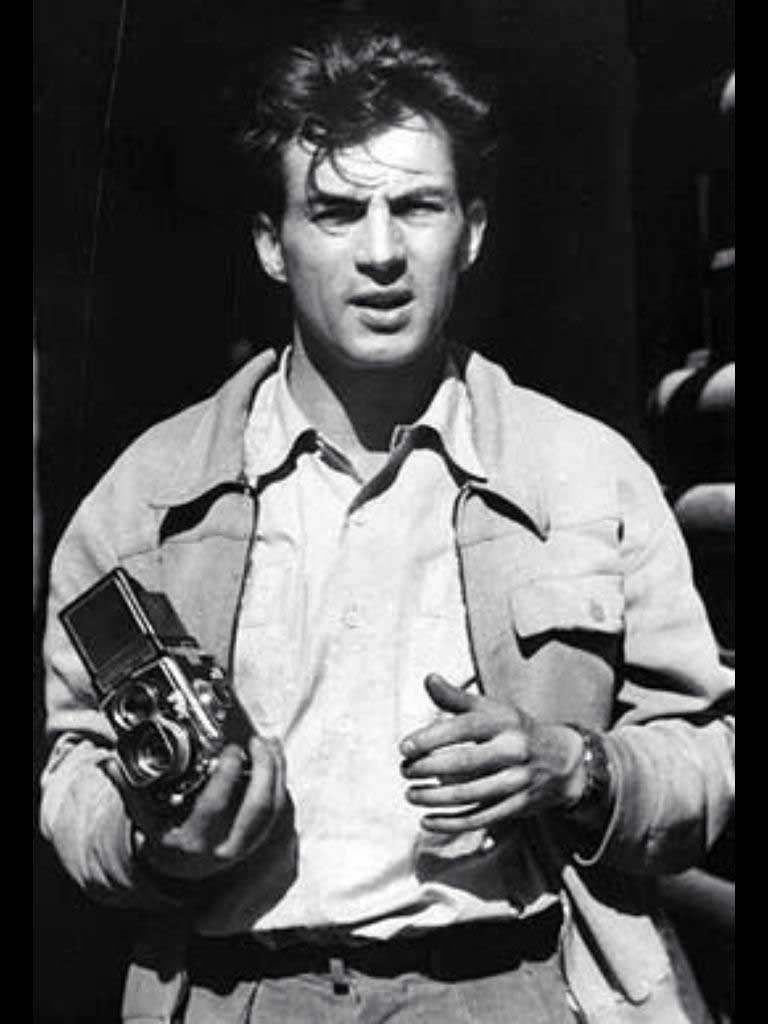

Defined by many as the world’s early master of color photography, Ernst Haas practiced photography as an artist: impressionist and emotional. A catharsis that translates into each of his photos; his way of seeing the world, the mundane and the less common was different from what was known back then.

Ernst Haas was born in Vienna on March 2, 1921. As a citizen of Hebrew origin, his life encountered some hardships during the years before World War II, which made him abandon his medical studies due to racial laws. He then attended the graphic institute in Vienna to study Fine Arts, but left it almost immediately.

In 1940, at 19, he decided to leave painting. As he claimed, he felt an early passion for photography, which was his first and true vocation.

In his first stage as a photographer at age 22, he began working for a photo studio in his city. Not long after, he became an independent photojournalist in the context of a troubled and battered Europe that tried (as most as it could) to heal the tremendous wounds caused by World War II, publishing his work in graphic magazines such as “Der Film” and “Heute”. His first photos portrayed the dire consequences of the conflict and the post-conflict.

It was one of his reports, entitled “Homecoming Prisoners” in which he would show a selection of emotionally heartbreaking photographs of repatriated war prisoners from across the continent returning to Austria. These images, captured between 1947 and 1950, earned him as a pass to international prestige and recognition, since the emotional strength they had had overwhelmed the public beyond expectations.

His works had been noted by the American magazine Life, which was already notorious for its photo-journalism activity along with notable photographers. The magazine sent him a proposal for collaboration, but Haas rejected it, since he enjoyed his freedom as a freelance photographer. He decides to formally join the famous Magnum Agency of his friend Robert Capa in 1950, in the name of the passion that already linked him to his new job.

Ernest was already recognized among his fellow photographers for the series of images he had taken to the prisoners of World War II. By that time, he had also formed a deep friendship with other important photographers of the time, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Werner Bischof for example.

This fact made him expand his field of interest, and begins to export his talent beyond the borders of Austria. He began to decouple his work from war issues and was inclined to more dynamic issues and everyday life.

In 1951, he moved to the United States and began to investigate color photography. He begins to develop his own unique visual language in which he takes as protagonist urban visions full of reflections, blurs and blurred trails of movement, the other aspect he began to explore along with color. This makes him start a new phase in his photographic career; a phase that debuts in 1953 with the publication of 24 photographs of New York in Life magazine, titled as “Images of a magic city”.

With this, he also begins his most productive and collaborative phase of his career. He collaborates with the best and most recognized graphic publications worldwide such as Look, Vogue and Esquire, to name a few. His experiments with color and movement were an innovative and revolutionary movement that redefined the canons of modern photography, which began to replace the classic black and white.

He continued publishing in Life magazine and collaborating with Magnum, as well as teaching. He taught his students to learn again, to free themselves from the prejudices and norms that existed until then. His contribution went beyond a simple addition of color to gray tones.

In 1962, he made an exhibition of colored photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and, in 1964, he was called by John Huston to handle the photography direction of the super-production “The Bible.” Throughout his life he published different books and received several awards, including the Culture Award of the German Photography Association, received in 1972 and the Hasselblad Foundation International Prize in 1986.

He died unexpectedly on September 12, 1986, due to a stroke.