Gerda Taro was the first woman to register a war with her lens. She captured the images that show the coldest side of humanity, keeping her eyes open where many prefer to look the other way. Many photographers return to give us a small eyesight to the hell of others; and sometimes, they just don’t come back.

Gerta Taro, whose real name was Gerda Pohorylle, was born on August 1, 1910 in Stuttgart (Germany). She was the daughter of a bourgeois family of Jews of Polish origin. Some know her work under the pseudonym of Robert Capa (whom many have considered the best war journalist in history), but in reality, Robert Capa’s name is just a brand in which Gerda and Andre Friedmann hid; but first things first.

In 1929, Taro and her family moved to Leipzig, shortly before the start of the Nazi era in Germany. She sympathized with the leftists, whom she supported instead of the Nazis. For that reason, she was subjected to protective custody, and in 1933, when the Nazi Party rose to power, she was almost arrested for campaigning against the government. Her whole family was forced to take measures to survive, so they had to seek residence in other countries and ended up separated, in different destinations.

Gerda decided to flee to Paris with a friend, where she went through a long list of jobs before discovering her passion for photography. She worked as a waitress, nanny, typist of a psychoanalyst and, finally, as secretary of the Alliance Photo Agency. That’s where she not only discovered her real vocation, but her soulmate, co-worker and adventure companion: Andre Friedmann, a Jew of Hungarian origin who tried to make a living as a photographer. Andre shared with Gerda all his knowledge about photography.

For a while, things mostly seemed to be going well, but the lack of employment and the need to generate income was becoming painfully evident, and it is precisely from this need that Robert Capa is born. Gerda and Andre invented a character with the profile of a well-known American photographer who came to work in Europe. Being so successful, they decided to sell his photos through his representatives, who would be themselves, and at triple the price of that of French photographers. The idea turned out to be very successful, as they soon received a large number of commissions and began to generate good revenue.

If any editor wanted to see Robert Capa or interview him, Gerda invented an excuse so that the meeting would never take place. In fact, she actually convinced the editors that Robert’s photographs warranted a higher expense than average. In this way, they managed to skip the anti-Semitism of many. “Taro and Capa were not merely reacting to their precarious economic situation. They were responding as well to the antisemitism of Germany and the increasing antipathy towards foreigners in France. And to elude the stigma attached to being refugees, they spurned every ethnic or religious label.” (International Center of Photography)

It was then that she adopted her pseudonym “Gerda Taro”; It was a name of basic spelling, easy to pronounce and with a similar sonority of Greta Garbo, an American actress of the time. Andre would keep the pseudonym of Capa. Both marked a style of photography in which it is often difficult to know who the author was.

At that time of their lives and their professional career, the Civil War arrives in Spain, in 1936. Without a doubt, it seemed like an ideal place to create a good reputation in the press and knead a fortune. The Civil War would be the springboard that would propel them to fame in the world of photography. However, professional motives were not the only reason for this decision. Both were moved by the social injustices they saw in the Spanish gentilic; injustices and hardships that they themselves had endured and overcome back in their homelands, which served to forge their political and revolutionary ideals that characterizes their works.

They traveled as Robert Capa, and visited many of the Spanish Republican fronts (both together and separately), the most know being the fronts of Madrid, Aragon and Barcelona. They also traveled to Cordoba, where Andre takes one of his most controversial and symbolic photos ‘The Falling Soldier’. It is still debated on who is the real authorship of the photo, and if the photograph was spontaneous or planned.

The couple witnessed many episodes of War, so they managed to make reports that were reproduced in renowned publications such as ‘Ce Soir’, ‘Regards’ or ‘Vu Magazine’. At the end of 1936 they made a Project in which Andre recorded while she took the photographs. The increase in publications dedicated to the historical development of the Spanish conflict transformed Robert Capa into a true media phenomenon. Nonetheless, at the beginning of 1937, Gerda and Andre (who kept the pseudonym of Robert Capa) distanced themselves.

She rejected Andre’s marriage proposal and from that moment, they continued their careers independently. Gerda signed her own contract with Parisian newspaper Ce Soir, and went to live in the Alliance House in Madrid without Friedmann. Her first publication was in the March 18 issue of Regards Magazine, which marked the beginning of her own works. She began to embark on her own path, in which she approached European anti-fascist intellectuals, such as George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway, and began marketing her work under the ‘Photo Taro’ label to publications such as ‘Illustrated London News’, ‘Life’ and ‘Volks Illustrierte’. Sometimes, she took pictures under a joint signature, “Capa & Taro Report”. In the same manner, Andre forged his own way and founded the Magnum Photo agency.

The first important report that was published under the signature of Taro was in ‘Regards’, on April 15, 1937. Her photographic attention was handled between the war front and also in the suffering of the Spanish civilian population. She was very aware of the power of photography. In Madrid, she photographed the ammunition factory and the Carabanchel district, where civilians were repressed with grenades with slingshots. Her works showed not only entertainment but an informative character that sought to change political decisions. She wanted to change the non-interventionist policy that Westerners had adopted about the Spanish conflict. It was a war photojournalism for propaganda purposes and full of political convictions.

Andre and his colleague David Seymour followed the same line of thinking, and among the three, they showed the destruction of the war from the perspective of the victims as a way of exerting pressure.

Death in Madrid

One of her most important reports of the Spanish Civil War was that of the first phase of the battle of Brunete, in which she witnessed the triumph of the Republican side. That report gave her a great international prestige and appraisement of different Magazines. After that report, she had a brief stay in Paris, where she met with Andre for the last time. Not long after, Franco’s troops began the counterattack, and Gerda decided to return to the battle front in Brunete. Her initial plan was to stay in Madrid to resume her coverage of the front for a few days, and then return to Paris. She witnessed the bombing of aviation and the defeat of the Republican side.

Her initial plan to return to France never happened, as she would, unknowingly, meet her demise in the eve of the trip back to Paris in a tragic (and almost absurd) accident during the army’s withdrawal as she was leaving the front.

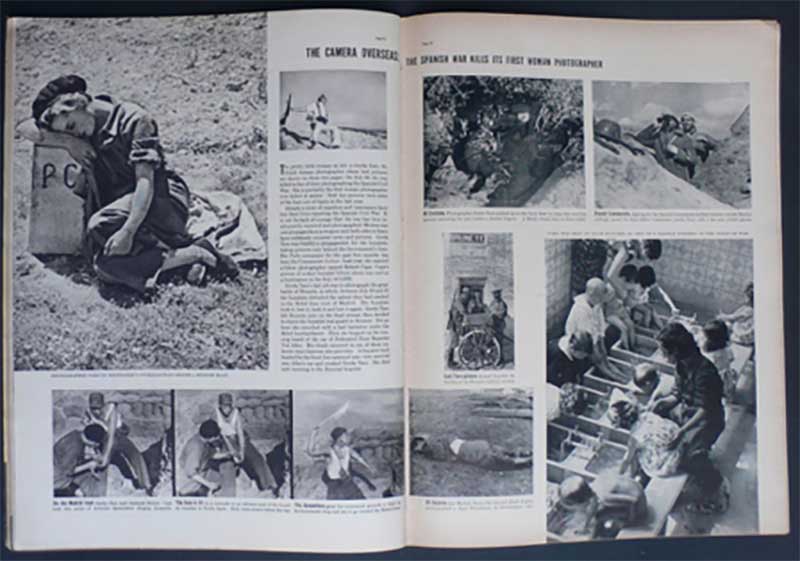

“The Spanish war kills its first woman photographer”- Life Magazine, august of 1937.

(Life Magazine issue reporting Taro’s death)

Gerda had climbed into the stirrup of a General’s car. During the air raid, some planes passed at very short height, which triggered panic in the convoy where she was traveling, making her fall to the ground. Unfortunately, a Republican tank backed down at that very moment and ended up running over Gerta by accident.

She was transferred to the field hospital of the 35th division (English hospital of El Goloso) in the Madrid town of El Escorial, where she died a few hours later, in the first hours of July 26, 1937, six days before her 27th birthday. Her body was moved to Paris and received all the honors of a Republican heroine.

The French Communist Party organized her funeral as a big commemorative act, which was attended by ten thousand of mourners, among them Capa, Seymour and Ted Allan. The party bought a tomb with a 100-year concession in the Père-Lachaise cemetery. Flowers and intellectuals surrounded her grave and on July 28, Ce Soir published a photograph of Taro framed in a solemn black frame. In death, she became a hero.

Franco’s destruction of the work of many journalists, the beginning of the Second World War at the end of the Spanish tragedy and the fact that Taro was associated with the communist ideology had dulled and silenced her work for many decades. But, in spite of everything, she will always have a deserved and unique place in history.