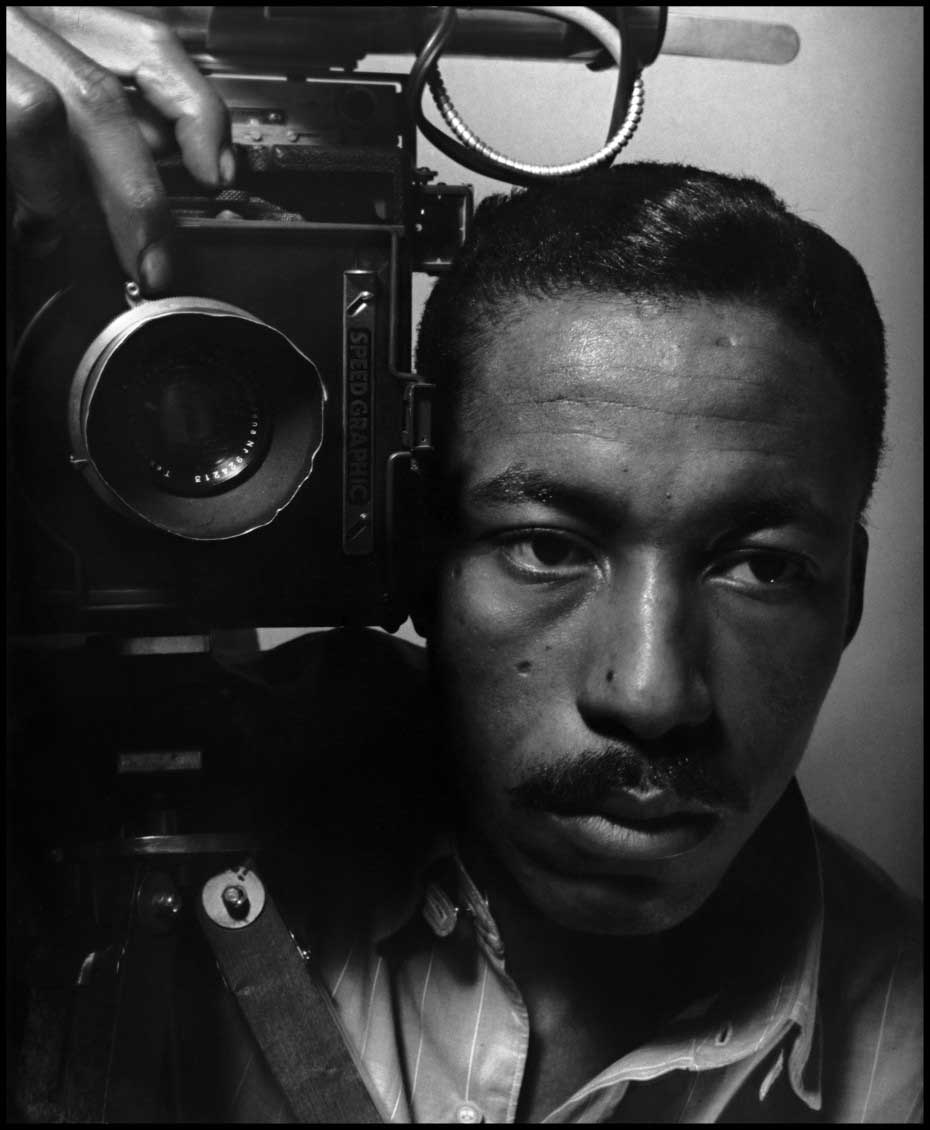

Gordon Parks’ photographs tell of a black world. Images that documented the life of the poor of America, of its workers and its inhabitants. Despite working within a cultural and ethnic background, Parks had the instinctive ability to show us a sensitive and objective reflection on the thousand faces of forced and discriminated people who struggled to emerge.

He has shown how the camera can transform itself into a powerful tool for socio-political criticism. The images of the American photographer have made visible the deep rift of the American territory, taking as a model simple individual stories with universal and symbolic meaning.

Gordon Parks was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, United States on November 30, 1912. He was the son of a modest couple. As a child, he was a shepherd boy, and then he attended a segregated school, exclusively for black people, where teachers discouraged students who wanted to pursue a higher education. He knew injustice and rage in a segregated America since a very early age.

In 1919 at age 7, he began to play the piano, and although he could not read or write scores, he composed his own pieces thanks to a system of musical notation that he invented for himself. His mother died when he was just 11 years old. His father then sent him to St. Paul, Minnesota, with his sister and her family, with whom he lived until he was 15 years old. He was thrown into the street due to a domestic dispute.

Fortunately, he got a job as a dishwasher during the day and as a pianist and singer in a brothel at night. His path in music led him to be in a musical band with which he already worked with by 1933. His luck seemed to last a short time, as the band broke up when they arrived in New York: the leader fled with the money of all the musicians. Around this same time, he got a job at the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

The contract with the CCC lasted for a year, so he had to return to Minneapolis, where he got a job as a waiter at the North Coast Limited’s railroad restaurant. He married Sally Davis and started a family. It was this job that made him interested in photography; thanks to some illustrated magazines that some passengers abandoned and which he checked frequently. Fashion photography had caught his attention, as well as a report about the impoverished peasants who were registered by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration.

This report made him realize the strength that a camera could have, and decided that this instrument could become his weapon against racism, poverty and social ills. He bought his first camera in 1938 at a pawnshop in Seattle. It was a Voigtländer Brillant that he acquired for $12.50. He started taking photos in Seattle and then went to reveal the pictures at a Kodak laboratory. George Eastman, the owner of the laboratory was so impressed with his photographs that he sponsored Parks’ first exhibitions.

Soon, Madeline and Frank Murphy offered him work as a photographer in their Frank Murphy’s store, a haute couture shop in Saint Paul. His success led him to Chicago, where he moved without his family. He began to work in fashion photography and portraying the rich women of the epoch, but he also traveled with his camera the poor areas of the south of the city, which would eventually win him the scholarship of the Julius Rosenwald Fund.

He developed a style that would make him one of the most famous photographers of his time. He broke the stereotypes while creating images of great expressiveness that delved into the social and economic impact of racism. He was able to maintain his devotion to documentary realism while allowing himself to make his own feelings evident, as evidenced by one of his first photographs, “American Gothic,” destined to become a definition of social injustice. He took it in a state of indignation, one afternoon after he was denied successively in a shop, in a restaurant and in a theater for being black.

Parks toured churches, streets and fields in the south portraying the daily lives of the victims of segregation (prayers, education of children and adults, meetings, mobilization speeches …), then the march in Washington of Luther King and finally, the members of the Black Muslims, a collective movement against the initiatives of integration of Luther King. The powerful portraits of African-American life in the mid-twentieth century of photographer Gordon are already part of the iconography of the United States. He died of cancer at the age of 93, on March 7, 2006 while living in New York.