Famous artists and photographers can be recognised by their style. Style is a combination of subject matter, technique, compositional components, the use of colour and other, sometimes very subtle, elements.

It can change through a career and some people have more than one style and change up, depending on the subject matter they are shooting.

Style is said to be a good thing to have, but do you actually want or need it? It is a deliberate narrowing of your photographic world. If like many of us, there is only one or two subjects we are truly passionate about photographing, then it does not matter. It is the difference between opencast mining and mining a rich seam of gold.

If you are only interested in shooting for yourself alone or operate in a small commercial market, then having one is not necessary, and in commerce it can be a liability. If, however, you are in a large commercial market, then you will have to specialise because so many photographers are available, there is no room for generalists.

If you manage to come up with a fresh and exciting new style then art directors or gallerists will snap you up, right? The answer is probably no. Like most people, they are more conservative than they like to think themselves. They will look at the work and ask themselves, “Will it sell? Will the public/clients/readers/collectors understand it?” And if they have not seen anything pretty close to it before, they will want you to prove it sells elsewhere and then come back. They need someone braver than themselves to use you first. Taking on something new can be risky for them, as there can be a lot of money at stake and a business to maintain. It could cost them their job if it goes wrong.

We have all seen those nature programmes. It is the Thomson’s gazelle that wanders to the edge of the herd looking for new juicy shoots that get eaten first. It is safer to stay in the middle. They will be able to appreciate your work from an aesthetic viewpoint, and it may be a refreshing break from the same old stuff that comes across their desk on a daily basis, but they will never use it. You’ll become a much admired, seldom hired photographer. A good way to break through is to have friend who works on a magazine, win a notable award, get a large social media following or get very lucky. When you hear these people say they want to see something different and exciting, what they really mean is, they want to see something much like they are used to but with a twist.

My own odyssey towards a personal style

When I became interested in photography, even before I had shot my first decent picture, I decided to take a less trodden path. I would look at magazines and adverts and think, “I can do that,” even though I had no experience of lighting or had ever seen the inside of a photographer’s studio. I just knew that the mechanics of photography would not be hard for me to master. I was correct because within 18 months I taught myself what I needed to know and went from taking pictures of London tourist spots to my present style. Style can take years to find but I immersed myself in photography and gathered what I liked and rejected what was of no immediate use to me.

I became seriously interested in photography in 1983 at the age of 21 and immediately began reading the amateur magazines and looking at as much images as I could. In the magazines were the works of master street photographers such as Cartier-Bresson, Brassai, Andre Kertesz and those of that ilk. I quickly came to the conclusion that I could never be as good as that and that hundreds of thousands or even millions had already been down that path. The chances of me being that good was pretty slim and I decided to try to tread a less rutted path. I wanted to trek a new path across some springy grass and get to a new vista. I did not know what my subject matter should be and to that end I began to actively look for inspiration.

My first influence was to be found in those same magazine pages and it was the now largely forgotten, Francisco Hidalgo. He would travel the world publishing books on major cities, using Cokin filters, multiple exposures and other techniques, in an impressionist manner. They were very colourful. I had a temporary job as a telephonist in an empty building where the workforce had moved less than a hundred yards away. I was the only one on the floor and I would read Amateur Photographer between calls and every week would order a new Cokin filter and outdated film. Every Sunday I would visit the London tourist spots with my bag of tricks and try to make something artistic out of them. Later that year I started experimenting with distorting the emulsion of the film. The technique created bubbles and distortion and lasted the test of time better than my filter pictures. Ten years later I started using it again on my road trips around Britain.

At the same time as doing what I called my “Impressionism” (it would probably better be described as Neo Pictorialism these days), I was looking at all sorts of photography including editorial and advertising. I quickly discovered that I could generally make out how a portrait was lit by looking at the catchlights in the eyes and the strength of the shadows. I began thinking about becoming a professional photographer. One lunchtime in a bookshop across the way, I came across the work of Rene Magritte and thought I would like to try something like that at some point.

That autumn I enrolled in a couple of adult education classes. In one of them I had access to a 5 x 4 camera. I bought some Polaroid and Ektachrome sheet film and attempted to create surreal advertising type still life images with half a dozen 500w Photax lamps. The other class was at what was then called the London College of Printing, where there was a library. At the same time, I scoured all the imagery I could, including advertising and illustration annuals and drew sketches of ideas for pictures. The following spring, I came across the work of first Cheyco Leidmann, then Guy Bourdin.

I did not like all of Leidmann’s work by any means but it was graphic and very colourful and there was nearly always some sort of surrealist incident in them – a thrown cat or a stuffed zebra out in the desert. He had two books out, Foxy Lady and Ad/Art. In Ad/Art he even had the technical details of each shot. I analysed the pictures to try to work out why they were so super saturated. The conclusions I came to were firstly, he put colour into his pictures in the form of colourful Lycra (Spandex) clothes or props and secondly, he would use flash in daylight, so that even on an overcast day the colours would zing. He would use an 18mm lens at f22, square onto the subject without any apparent distortion. I could not afford an 18mm lens but I soon realized the smaller scale of my London back drops needed a less wide lens. I settled on 28mm, which became my standard lens until I discovered the zoom lens 25 years later. 50mm was like a telephoto to me.

About the same time I came across the work of Guy Bourdin in an old advertising annual. It showed about 4 of his shoe pictures for Charles Jourdan. In the same book I found another two pictures in the same sort of style and these six pictures influenced me profoundly. When I had eventually digested all this and finally went out to take pictures, it was three people who were at the front of my mind: Magritte, Bourdin and Leidmann.

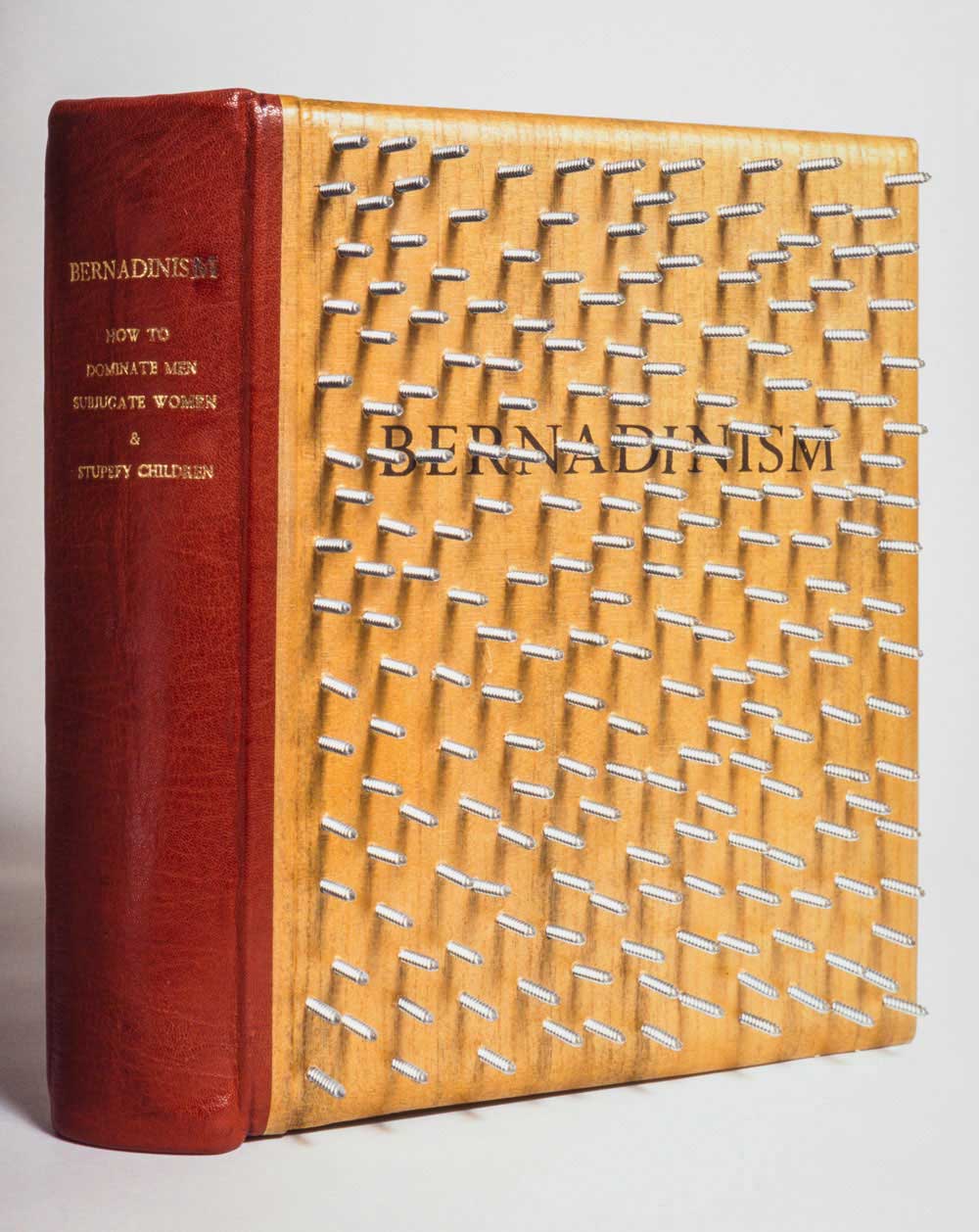

The following year, 1985, I stumbled across Bourdin’s work in French Vogue and followed him until he disappeared from it in 1987. He died in 1991. There were no books or exhibitions and I saw no more until his book in autumn 2001, a month after my first book, Bernadinism: How to Dominate Men and Subjugate Women, came out. I was to win Erotic Photographer of the Year for it. Before that though, I thought it a shame that he had been forgotten and that there were only 3 pictures of his on the internet so I created the first Bourdin site on the net with the few magazine pages I had in my possession in the spring of 2001. Not knowing there was a Bourdin book already in the works, I tried to interest my own publisher in putting out a book. He only vaguely remembered him.

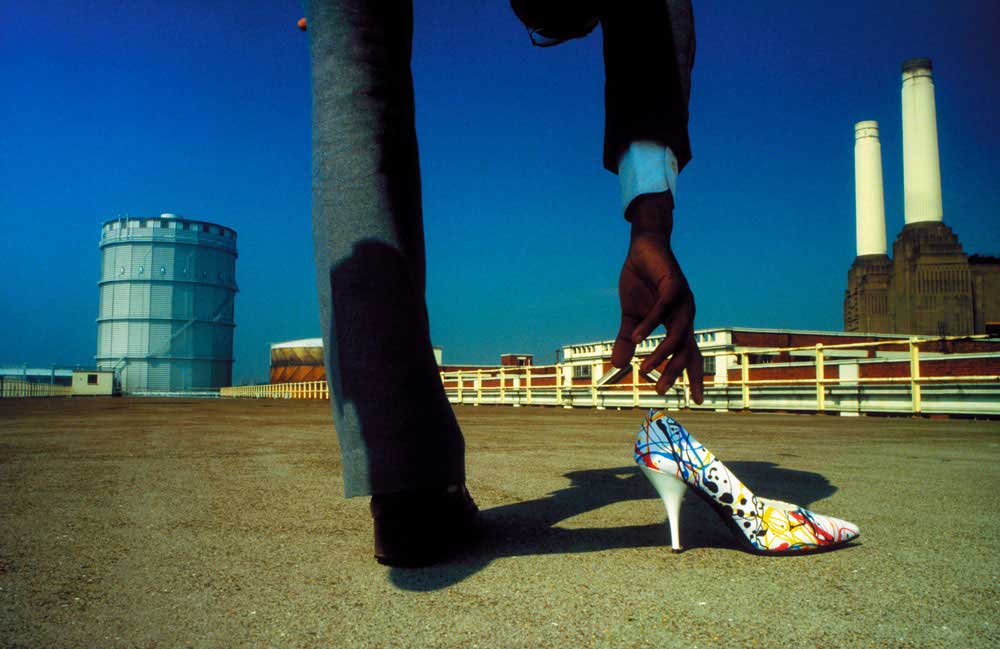

My most seminal pictures at that time was a series entitled, The Fetish. I had assimilated a lot of photography, sketched out some ideas on paper in the spring of 1984 and by the summer I was ready to go. I stumbled across an old wrecked goods yard with three disused buildings next to Battersea Power Station in London and it was there I really learned to photograph. I am largely self-taught and have never been an assistant. I had newly moved to south London and knew no one or anything about model agencies. For my first pictures I used myself as a model. When the light was right, I could take off at the drop of a hat as I did not have to make an appointment, days in advance.

One of my first ideas was a picture taken from a low angle of a man balanced on one leg picking up an object. The object needed to resonate some sort of significance but I didn’t know what it should be. It was then that I came across a Jackson Pollack patterned shoe in a shop and it immediately reminded me of Bourdin, so I used that. After shooting the picture I thought I would make it into a series. I shot others over the next several years and eventually won the Vogue/Sotheby’s Cecil Beaton Award for young photographers with it in 1987. All the pictures featured me (although you never see my face) and the series is called The Fetish.

The pictures readily fell into place and by the autumn I had quite an individual looking portfolio. Within about 18 months of taking up photography I had a style. One I could expand to encompass most of my preoccupations and the way I thought.

In the summer of 1987, I started reading about the surrealist and Dadaists. They both had manifestos. I wondered why people no longer wrote them and I decided to write one myself to make concrete my thoughts and approaches to my own photography. It was called: The Bernadine Universe

Alva Bernadine

Alva Bernadine makes photographs and films. By using themes such as surrealism, sexuality and violence, Bernadine touches various overlapping topics and strategies. Several reoccurring subject matters can be recognised, such as mirrors, shadows, optical effects and representations of the female form. The work is filled with invented surreal scenarios, witty events, troubling scenes from movies that were never made and almost hallucinatory images that invoke narrative, prompting you to imagine what came before or what is about to happen. They are not only about desire but the problems that go with it. Bernadine was born in Grenada, West Indies and grew up on the outskirts of London. He won the Vogue/Sotheby’s Cecil Beaton Award as a young photographer and has since worked for many prestigious magazines and became Erotic Photographer of the Year for his first book, Bernadinism: How to Dominate Men and Subjugate Women.