Meet Marina Marinkovic, a multifaceted talent from the Netherlands. She stands out in the world of photography, not just as a photographer but also as a part-time MD, driven by a profound passion for visual storytelling.

Her entry into photography is as fascinating as her work, having started in her forties at the distinguished Fotoacademie Amsterdam’s applied photography department.

Previously, Marina devoted her time to the demanding field of ocular oncology. It was during this phase that she encountered deeply moving and significant stories, emotions, and experiences. Bound by doctor-patient confidentiality, she couldn’t share these poignant narratives. However, life steered her towards her true passion: photography. Embracing it fully, Marina found in photography a liberty to express herself, free from the confines of medical ethics. This new path allowed her to share the silent stories she had witnessed as a physician.

Marina excels in capturing the beauty of small, personal moments. As a “fly on the wall,” she immerses herself in documentary series and connects deeply with her subjects in portrait photography. Her work, characterized by a deceptive simplicity, unfolds its complexity upon closer examination. She is deeply drawn to themes of caregiving and the performing arts, intrigued by individuality, vulnerability, and inner strength. With her camera, Marina explores these themes, shedding light on the often-ignored aspects of life that enrich and diversify it. Marina believes, “The camera makes me feel free. Free to listen, to play, to err, to dig, to wander, and to learn new things.” With this freedom, she aims to foster understanding and tolerance through her photography, bringing to light stories that are often left untold.

Join us in exploring Marina Marinkovic’s captivating journey as a photographer and the powerful stories she tells through her lens. [Official Website]

As a medical professional and photographer, you have a unique perspective on storytelling. Can you tell us more about your journey from medicine to photography and how it has shaped your approach to visual storytelling?

Medicine to me is a craft. The main skill you need to master to excel as a doctor is listening to the patient in front of you. I think this is even more important than having amazing surgical skills for instance. I feel that years of focussing on the verbal and non-verbal messages of my patients helps me in finding the essence of the story of the people and subjects I photograph.

Your project “Menopink” explores the often-taboo topic of menopause. What inspired you to delve into this subject, and how has your personal experience influenced your work as a photographer?

Since my medical work is so focussed on the other, at first my photographic work developed in that direction too. To be given permission to capture and share someone’s story was and remains very special to me. On the other hand I came to realise that photography is also a means of showing my own story. I find I am drawn to subjects that are getting more and more personal.

In your project statement, you mention the invisibility and eerie silence surrounding the process of aging as a woman and going through menopause. How do you believe your photography can break this silence and contribute to a better understanding of women’s experiences at this stage of life?

I was in surgery. There was a small team and we were working very close together. One of the scrubnurses was suffering hot flashes. Since I had experienced them too I asked for the temperature in the room to be adjusted and we talked about menopause for a bit. I then noticed the residents and other nurses trying to listen in to our conversation and being a bit uncomfortable. Even in medicine, inside a hospital, menopause is a taboo subject. Getting older as a woman is taboo. The best antidote for taboo is talking about it. It is as simple as that. And I do hope that this series will get some people talking.

Your images are described as appearing simple and clear at first glance but carrying deep messages. Could you explain the creative process behind capturing the complexity of women’s experiences during menopause in your photographs?

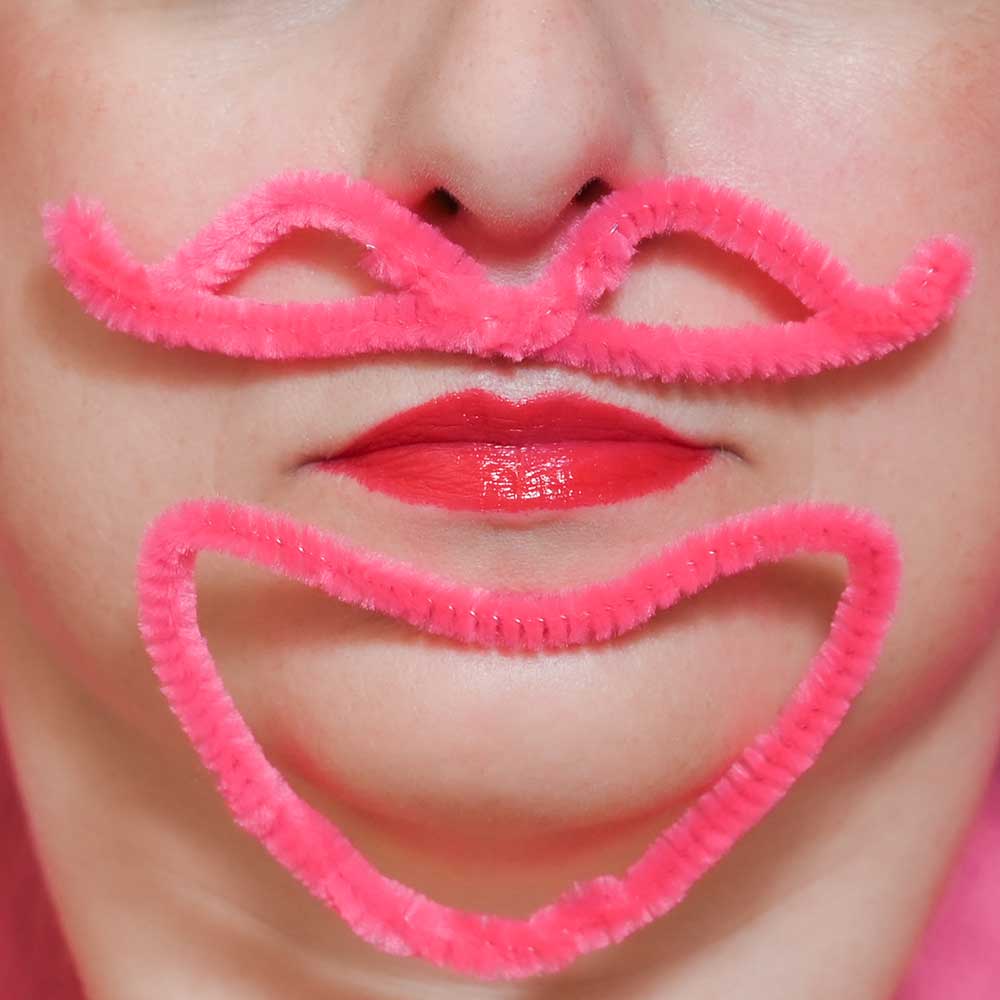

The start of this series was kind of scientific. I listed my own symptoms and read on the subject extensively. Than I made a shortlist of the most common complaints in menopausal women and made small drawings of ways to depict them. I love sketching ideas! I also started collecting pink props I kept in a box in my living room and played around with. After some months of collecting and pondering I shot the series in three nights.

“Menopink” references the polished visual image of femininity often seen on platforms like Instagram. How do you navigate the balance between challenging stereotypes and embracing the power of visual communication in your work?

I wanted to be clear and honest about the subject. At the same time I too am infused with the stereotypical portrayal of women so I played around with that. I depicted symptoms of menopause in a way that is pleasing to the eye. Clear pictures, retouched, showing skin. I wanted to draw the viewer in only for them to then slowly discover they had been lured by a portrait of the aging female. Also I overused the colour pink as a tongue in cheek reminder of the images of women we are spoon-fed.

What are some of the artistic or photographic influences that have had an impact on your work and your approach to visual storytelling?

The first photobook I bought was Raval by Joan Colom. Colom wandered the same streets in Barcelona time and time again and distilled a visual story that to me is extremely close up and personal and universal at the same time. A good story can quite literally be around the corner.

Nicole Segers and Irene van der Linde, a photographer and a journalist who have been working together for decades produce stunning books that opened my eyes to the power of collaboration and to the need to invest time.

Also I love going to museums and theatre and get energised when meeting artists, craftsmen and scientists who imagine and create for a living. Creating is contagious.

You’ve mentioned that the camera makes you feel free. Could you delve into how this sense of freedom influences your photography, especially when addressing sensitive topics like menopause?

As a photographer I am free of the expectation of exuding stability and neutrality that comes with a white coat. I can show emotions. I am allowed to be naked both literally and figuratively.

As a photographer, what kinds of stories attract you the most? Do you have recurring themes or specific areas of interest in your projects?

I am attracted to stories that revolve around individuality, vulnerability, and inner strength. I find that this often leads me to subjects touching on healthcare and disease and on performing arts.

In your opinion, how can visual storytelling, such as photography, promote understanding and tolerance in society?

Bringing subjects to light lessens their burden I think. It is like having an understanding friend or GP. Once you finally told someone what you were embarrassed to share you feel lighter. I think visual storytelling can do that too. Also, when you are exposed to ideas or images more often they might grow on you.

Besides “Menopink,” can you give us a glimpse of your future projects or areas of exploration in photography? Are there particular themes or stories that you’re excited to tackle in the future?

At the moment I am wrapping up a project called An eye for an eye. Over the years I have surgically removed dozens of eyes and I have always been struck by the ability of patients to pick up their life after such lifechanging event. I went and met 20 people with an artificial eye in their own homes. We talked about the experience of losing an eye and I photographed them. I was curious about the way their prosthesis influenced their self-image and the way they are perceived by others. The people I photographed had the expertise and I came to them to learn. This reversal of roles was important to me. Like the “Menopink” project this series is quite personal.