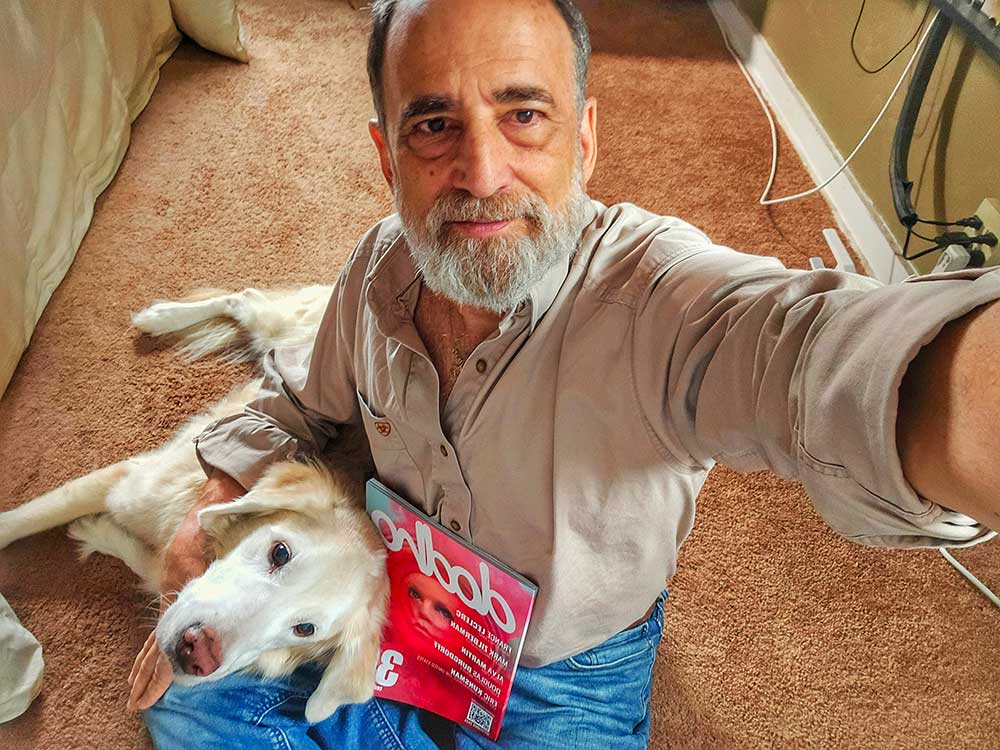

Today, we are pleased to introduce Mark Zilberman, a photographer whose passion ignited at the age of six when he acquired a Kodak Instamatic 104 during a family trip to Washington, D.C. Largely self-taught, he enhanced his skills at Arizona State University and by assisting renowned photographers in New York.

As a freelance photographer in New York City, Mark contributed to magazines like BusinessWeek, Forbes, and Eastern Airlines, and engaged in graphic design projects. His focus later shifted to photojournalism, leading him to document events in Gaza, the West Bank, Panama under Manuel Noriega, and Nicaragua during the Sandinista-Contra conflicts.

After pausing his photography career to earn a Master’s degree in Social Work and dedicating over 20 years to that field, Mark returned to photography, embracing the digital era. He rediscovered his love for photojournalism and street photography, becoming a finalist in international competitions in countries such as Japan, Greece, Hungary, Belgium, Sweden, Italy, the USA, France, and Iran.

Applying his documentary style to wedding photography, he captures authentic emotions with the eye of a street photographer. In this interview, we’ll explore how his experience in social work has influenced his artistic vision and his approach to portraying the world. [Magazine]

You mention that your photography journey has bookended your life, starting at age 6 with a Kodak Instamatic 104. What memories do you have of that first experience, and how did it influence your passion for photography?

My strongest memory of that moment was the bright yellow box that the camera came in. Everything from Kodak was packaged in that yellow. Hence the name given to Kodak as the Great Yellow Father. The loss of Kodak to bankruptcy felt like a gut punch to me when it happened several years ago. Kodak was a very beneficent corporation that I have fond memories of. Anytime you would call them and request education materials they would show up in the mail in quantity. They were dedicated to the art and craft of photography. They were at the center of the economic, social and artistic life in Rochester. It’s a true shame that they no longer but they were.

During your early years, you worked as a freelance photographer in New York City, collaborating with magazines like BusinessWeek and Forbes, and with graphic designers on annual reports. How would you describe that stage of your career, and what lessons did you take from it?

Of course, I learned a great deal during this period of my life. The obligation to use positive transparency film (aka chrome) required a great deal of precision in creating an image. The image you would get back from the lab was the actual film it was in the camera. There was absolutely zero latitude for errors in exposure. On the other hand, it’s only made me appreciate digital because that gives me so much opportunity in the processing part of image making.

I’ve nothing but the highest respect for people who pursue photography professionally and commercially. It takes enormous skill and commitment. I found at this point in my life constantly asking myself “What do they want?” It can be deeply frustrating when you are trying as hard as you can and not getting work and or respect. Commercial photography is very much driven by the styles of the moment. You can be hot one moment and quite cold the next. For many people what they do for a living is intimately tied into their own self-esteem and identity. At least for me that was the case. I found it to be an emotional roller coaster. Moreover, one can become well-known for a particular style. I think this can really interfere with one’s artistic growth. Many professionals faced with this situation keep their professional and personal work separate. Overall, though for me this way of life was not tenable and I chose to go a different direction. Which I think was the best decision for me. Moreover, I think the things I have gained in the life I lived without photography contribute greatly to my work currently.

Your interest shifted towards photojournalism, leading you to photograph in places like Gaza, the West Bank, Panama, and Nicaragua during significant historical moments. What motivated you to document these conflicts, and how did these experiences affect your perspective as a photographer and as a person?

I was motivated to photograph these conflicts because these were the conflicts “of the moment”. In the broader picture, there was a change occurring within me. Initially photography as a career appealed to me because it was what I perceived to be an exciting and glamorous life. And it was that for a while. But within me was the need to be involved with something more/other than that. I had always been a socially and political conscious person. And I was becoming increasingly attracted to the work of photojournalists who were doing great work. There was James Nachtwey, Sebastiao Salgado and W. Eugene Smith. I could sit with these people’s work and pore over them for hours. That was kind of peculiar because they weren’t the most pleasant situations to see pictures of. Nonetheless the images were gripping and quite effective. The trips I took (and traveling in general) gave me insight into the way my country (USA) is looked at abroad. It was not always pleasant. At the same time, I had the opportunities to meet with very fascinating photographers who spent most of their time traveling the world to document conflicts. Their lives and their perspectives were quite unique in my opinion. They had seen so much and had so many experiences and came to know people that could not be had or known otherwise. Photographically, the images had to have real content. They really couldn’t skim the surface and depend on composition, lighting etc. There had to be something going on. A good image hits would hit me like a sock in the jaw. And I still feel that way now. The image doesn’t have to be about something dangerous and gritty and bloodied. But if an image does not make me feel something immediately, I don’t care if all the elements are neatly placed and don’t overlap. They have no worth to me. Conversely, an image that hits me may break all the rules of composition and current photographic fashion, it can still be great to me.

After these experiences, you decided to leave photography to earn a Master’s degree in Social Work, a field you’ve worked in for over 20 years. How has your work as a social worker influenced your current photographic approach?

I think my work as a social worker influences my work in photography in that images need to have emotion. It doesn’t have to be any particularly strong emotion. But it’s got to make me feel. That could be humor. That could be sadness. That could be transcendence. The life of the social worker is all about being in touch with emotions, the need for social justice and problem solving. I feel I’m still evolving in my photography. I’m not sure how much of my current work incorporates those feelings. Though I feel I am on the right path to finding the nexus of my work in social work and in my work in photography.

Following a 20-year hiatus, you returned to photography and embraced the digital world. How was that transition, and what attracts you to digital photography compared to analog?

Digital was a challenge. It took a lot of work and experimentation to feel confident with. But I’ve come to the point where I really enjoy it and would never consider going back to analog. Frankly, as I spent 10 years working professionally with analog, there’s nothing romantic about it to me at all. The current work that I do now with flash could not be done with film. It would take so much luck. That could speak to my lack of technical mastery of flash photography (Btw, anyone interested in flash should study the work of Barry Talis. Nobody else comes close). But I need the instant result to confirm or not the success of the picture. I understand the appeal for (particularly young people) for film. For many it provides a way of connecting to a time they never lived through. We see this in so many areas of life. The longing for a past that exists only in their imagination. That’s quite normal, of course. But I don’t miss hours and hours spent in the darkroom inhaling acetic acid. Print after print trying to get it just right, costing a dollar more for each print. Now I just move the dial. I’m good.

Revisiting your past work, you felt most connected to images resembling photojournalism and street photography. What do you think draws you to these genres, and how are they reflected in your current work?

I think what draws me to these genres is relevance. Importance. And the ability to communicate emotion through these approaches. And I think this is consistent with that which I discovered within me through the course of my life. Looking back at my work from the past, a lot of it was specifically for clients who had a need for an image to accompany something in the publication or particular media. They need to be lit well. Good composition. Accurate color. Mostly dead though. But a lot of the work that I did that was more spontaneous and about something was/is more satisfying to look at. Spontaneous, and even accidental images, frequently are the ones that I like the best. I think the images that come out of photojournalism, and in particular street photography, are simply more interesting. Rarely is a commercial image interesting to me. I can certainly respect the craft. Immensely. But I am unlikely to dwell much on it.

You’ve been a finalist in international photography contests in countries like Japan, Greece, Hungary, Belgium, Sweden, Italy, the USA, France, and Iran. What do these recognitions mean to you, and how have they influenced your photographic career?

I can’t hide my excitement over having my picture (and me) recognized. There’s no question that I like notoriety. At the same time though, as I’ve had additional awards, it’s not quite as exciting as it used to be. Nonetheless it is still a very pleasant experience. But what I want to scrupulously avoid, is to do what I did when I was in commercial work. To be asking myself “what do they want?”. I am doing the work that I want to do now because I purely enjoy it. Not because I’m trying to win awards. Because frankly I haven’t a clue as to know “what they want”. I’m following my own nose. At this point my life, it’s all about me. I’m in this for what it gives me and what it might give others. Period.

You photograph weddings in a non-traditional way, focusing on a documentary style. What inspires you about this approach, and how do you apply your street photography experience to these events?

In terms of work style in wedding photography, documentary wedding photography suits my temperament. I’m moving around continuously and spontaneously shooting. I’m not posing. I’m not pulling family members out of their very expensive event to create ridiculously posed images. Images that will be looked at just once and never again. Images that will again make people feel something. Capturing emotion. And there’s plenty of that at a wedding. Another thing that is very appealing to me about doing documentary wedding photography (in contrast to shooting on the street) is I rarely get any kind of hostility from the subjects. It’s become increasingly difficult to photograph on the street without provoking anger and indignation. I still find it difficult to navigate somebody who confronts me taking pictures on the street asking me all kinds of questions that I really have no answer to. This doesn’t happen at weddings in my experience. These people know have come to the wedding are getting a free meal so they don’t get bothered. This is also why I more and more am doing my street photography at public events because people seem to be more accepting of cameras being present. At the end of the day, I’m trying to make interesting pictures that have feeling in them. I’m not looking to invade anybody’s privacy. I mean no harm. Documentary wedding photography gives opportunities for making pictures that I like. Unfortunately, I don’t find in the United States a big market for this kind of wedding photography. I think it’s much more common in Europe and particularly the UK.

You mention seeking to capture strong emotions, both at weddings and on the street. How do you manage to capture these emotional moments, and what significance do they hold in your work?

Capturing emotional moments for me in photography is somewhat of an experience of luck. I shoot a lot. But it’s in the editing process where I find the emotion. Of course, emotional situations will produce opportunities for emotion (political demonstrations for example). So, I’ll direct myself to those situations for shooting opportunities. But these kinds of images can be consequences of very unemotional situations. Because of the capability of camera to freeze a moment you can well end up with a representation of emotion that was never there in the first place. I’m okay with that. I’m not really trying to represent what was going on. All I am concerned about is the image at the end. In this way I’m not really doing photojournalism. That’s supposed to be about what’s going on at that time. And I don’t think I’m really good at that. I think there is an experience that is the image itself. The experience of looking at an image. That in itself is an emotion that may not be available in any other way other than from the still image.

After such a diverse career with many experiences, how do you see the evolution of your photographic style, and what motivates you to continue exploring new areas?

I think the evolution of my photographic style is in parallel to the evolution of myself. I can see in hindsight how that has been at work. There’s no separating what is going on within us from what we’re doing with our photography. At least not me. And even if you do try to separate them that in itself says something about what’s going on and you. What continues to motivate me is that photography has so many ways you can pursue it. Currently I’m enjoying what I am doing with street photography. But that could change. I find the images that come out of wildlife photography very intriguing. I have a home in rural Upstate New York and am trying to take advantage of that. But that’s a specialty that takes patience and discipline. Sometimes in short supply with me. You asked what motivates me to keep exploring. At base it still a joy to look at an image as it just appears. As it did when the image came up slowly in the developer tray and now as it appears on the back of the camera, it’s all still magic and delight. I’m at a point in life when many people retire. They’ve suffered through years of working at something. They’ve been counting down the days till it ends. Unfortunately, many have given little thought as to what they’ll do then. Sadly, many soon discover themselves drifting into malaise. I don’t see that with myself. I’m blessed to have this medium. I don’t take it for granted.

Can you share any memorable anecdotes or experiences from your photographic travels that have left a significant mark on you?

I was in Panama one year before the American Army came to “resolve” the matter with Manuel Noriega. There was an increasing amount of anger and hostility toward the regime. And from the regime toward the public. It was an immense demonstration and March proceeding down the Via España. I was in the middle of it with my camera. That was a huge mistake. Veteran photojournalists that I met there knew to stay on the periphery. I, in my sense of youthful impunity, wanted to be “in the middle of it”. That dumb shit was about to get an education. At one point the crowd rounded a corner where the road was leading directly into the stronghold of Noriega and his private army. You knew them because they were always dressed in black and were heavily armed. Thankfully I was far back. However, as the crowd rounded the corner, Noriega’s army fired live ammunition directly into the crowd. This caused a huge panic to occur within this crowd that rippled all the way through it. I was many blocks back nonetheless everyone around me started to run, screaming and panic. I just knew at that moment I had to keep on my feet. Otherwise, I would be trampled to death. I did succeed at that. Barely. CS gas was all over. I could barely keep my eyes open to see. I learned what the expression “heart ripping out of your chest” meant. I managed to get out of the crowd into relative safety on the side. But I could not in any way relax for quite a while. I then started running into the other photojournalists. To my surprise they were basically bored with the experience. They didn’t see such good pictures coming out of it. It was just another demonstration. Just another situation with live ammunition being shot. Not a big one. It was at that point I started to question whether this was for me. What was wrong with me? Could I keep doing this? It wasn’t until years later when I was studying and working in social work, and I began to understand a little bit about neuroscience and addiction, that I began to understand what was going on. There’s a phenomenon called “tolerance”. This is what happens as a substance user consumes their substance. It takes more and more to get the same feeling. What happened in one drink now takes 10. And for those photojournalists who found this experience unremarkable and boring, this is because they have developed some tolerance to their own brain chemistry. This can be what drives some people to do even more and more dangerous things. It can take a lot of personal insight to recognize what’s going on inside oneself. It’s vital to do so if only to maintain longevity.

Looking to the future, what projects or themes are you excited to explore in your photography, and how do you envision your art evolving?

Couple of years ago I had the good fortune to be in a photography workshop given by Magnum photographer Chien-Chi Chang in Jersey City. He showed pictures from the time when he could gain entry to a mental asylum in Taiwan where all the residents were chained to each other. I never heard of this before. It was impactful. This past March I was on a photography workshop being led by Maciej Dakowicz in Mumbai India. We were in a mosque where there were a number of people lying on the ground on mats. At one point I came across a young girl/woman who was sleeping, but had a chain extending from her wrist to a post about a foot away. I didn’t understand what was going on. I didn’t speak Hindi. But I looked to the man standing next to me for explanation and he just gave the signal with his hands circling his head that she was mentally ill. I took that picture and it was very impactful to me. I then learned that people with emotional distress come to this mosque in hopes of relief from their mental illness. I’m hoping to do a long-term project doing portraiture of mentally ill people in chains. This would be an opportunity for a nexus between my experience in mental health as well as photography. I’m looking into this now. I don’t think it can be that simple to find opportunities where I’ll be let in. But I’m going to try. And I wonder what kind of pictures I’ll produce. I’m not sure my current style suits it. What I hope to portray is the dignity and humanity of these individuals who are burdened both by their mental illness and the restrictions imposed upon them vis-à-vis chains. Keep your fingers crossed.