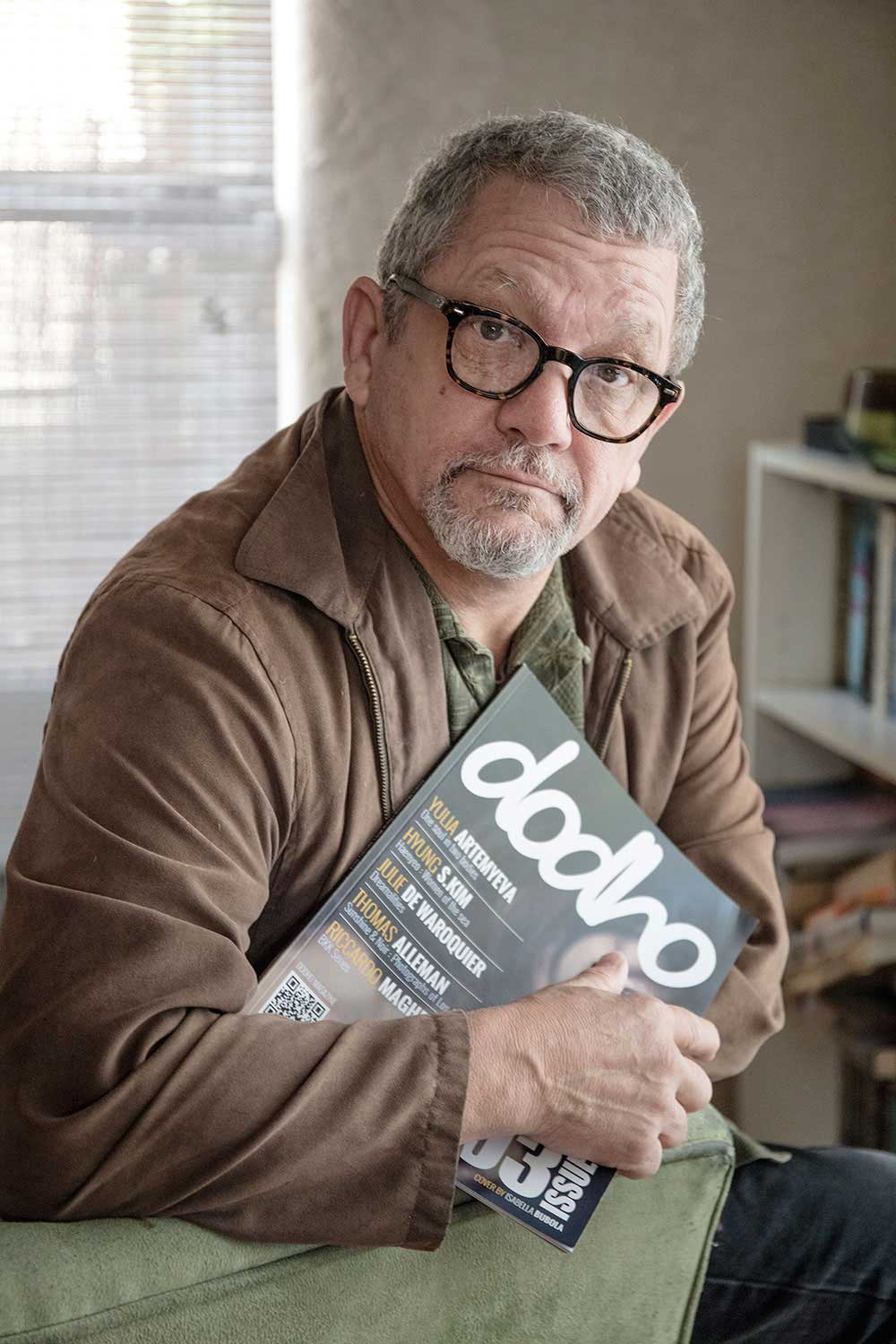

Thomas Alleman was born and raised in Detroit, where his father was a traveling salesman and his mother was a ceramic artist. He graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in English Literature.

During a fifteen-year newspaper career, Tom was a frequent winner of distinctions from the National Press Photographer’s Association, as well as being named California Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1995 and Los Angeles Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1996.

As a magazine freelancer, Tom’s pictures have been published regularly in Time, People, Business Week, Barron’s, Smithsonian and National Geographic Traveler, and have also appeared in US News & World Report, Brandweek, Sunset, Harper’s and Travel Holiday. Tom has shot covers for Chief Executive, People, Priority, Acoustic Guitar, Private Clubs,Time for Kids, Diverse and Library Journal.

In the late1990s, Tom exhibited “Social Studies”, a series of street photographs, widely in Southern California. He’s currently finishing “Sunshine & Noir”, a book-length collection of black-and-white urban landscapes made in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles. “Sunshine & Noir” had it’s solo debut at the Afterimage Gallery in Dallas in April 2006. Subsequent solo exhibitions include: the Robin Rice Gallery in New York in November 2008, the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR in October 2009, the Xianshwan Photo Festival in Inner Mongolia, China, in 2010 , California State at Chico, in 2011, and the Duncan Miller Gallery in Los Angeles, February 2013. Fifty-three of Tom’s photographs of gay San Francisco, shot between 1985 and 1988, debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December 2012, under the title, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws”. [Official Website] [Print Version] [Digital Version]

Can you tell a little about yourself?

I’m a commercial and editorial photographer, living in Los Angeles. I spend 15 years working for newspapers here and in San Francisco and Detroit, and then began working for national magazines like Time, People and Business Week in 1999. I’ve been doing personal projects since the mid-80s, beginning with a ten-year documentary about my family; in the last 15 years, I’ve done (mostly) urban landscapes in (mostly) American cities…

How did you get interested in photography?

I was a very ambitious young moviegoer when I was in high school, and used a friend’s 35mm camera to practice the horizontal compositions I’d seen in films. Later, during college, my interest shifted from cinema to literature and writing, but I realized, at the end of my studies, that I didn’t have enough life experience to write the novel I’d been planning—so I retreated to photography as a way to participate in the wider world and learn about how things worked…

What inspired you to take your Sunshine & Noir:Photographs of Los Angeles Series?

I’d been hoping for years to make a series of pictures in LA during the fall and winter—which are the seasons of shimmering light here. After 9/11, my New York magazine clients turned their attention to Ground Zero and the Afghan war, so I was unemployed for three or four months, and I took that opportunity to begin walking in LA’s many strange neighborhoods, to shoot that project. As most Americans were, I was shattered, horrified and alienated by those events in New York, and so I sought, in the first months of that walkabout project, to make pictures that represented my dark, confused mood. Later on, as I became committed to a book-length collection, I learned to make pictures in other emotional keys: elegiac, cheeky, deadpan, lyrical, funny…

Three words that describe your works?

Layered, aloof, hermetic.

How would you define your general style of photography?

“Psychological Documentary”? “Portraits of an Urban Landscape”?

In your opinion, what makes a good fine art photograph?

“Urban photography” is a pretty wide notion. Sticking only to my own little corner of that long tradition, I’d say that vantage point matters most. My interest—as a practitioner and especially as a viewer—is not aroused by making or beholding a simple, direct document, whose purpose is “simply” to confront the facts of the world and to preserve or celebrate or damn them with a straightforward rendering. I want to use those elements—the built environment, infrastructure, clouds and trees, passing pedestrians, cars and signage—to create a layered tapestry of line and tone in a two-dimensional artifact, like an abstract-expressionist painting, without regard to the hegemony of any nominal subject. So, where one stands matters immensely. Moving to the left or right just a step, or forward or backward just a little, reorders the relationships in the picture—things next to other things; the edge of one object and the silhouette of another; the balance between foreground and background, etc. Those aspirations are almost always thwarted by my own inabilities, but someone like Lee Friendlander succeeds at that continuously and miraculously, and so his work is my lodestar.

What do you think makes a memorable project or photograph?

The best projects are sustained interrogations of a clearly expressed idea. That idea is often about “the world itself”, but my favorite projects, from myself and others, always involve the photographer’s deep embrace of photography as they pursue that idea. For me, a great project always includes an interrogation of photography itself: how does that photographer push at the boundaries of what photography can do in this particular situation?

How do you know you got the shot you wanted?

As someone who’s been doing photography for a long time, I’m painfully aware that there are two or three moments at which one decides or realizes that they “got the shot”. I can be reasonably confident, standing on a streetcorner with camera in hand, that I’ve nailed the best version of the picture before me in a given moment, only to learn later, as I view and edit my work, that my whole approach to the subject was misbegotten in the first place, or overwrought: there was less there than I felt at the moment; the actual picture doesn’t matter. So, as I’m shooting, I try to give the “editor”—which is me, later on—a variety of views to sift through. Mostly, I try to achieve a balance, while I’m in the field, between complete emotional engagement in the current moment with a corresponding aloofness which is analytical and very calm; thereby, I watch myself work through the contents of a frame, and I try to identify what the elements and aspects are, and which can be truncated or just suggested, and which foregrounded and emphasized, and I shoot my way though a tour of those possibilities.

Your idea of the perfect composition?

A multitude of planes and sources of information, gesture and line, almost bursting into chaos, corralled “at the last minute” by the deployment of frame and the timely clicking of the shutter.

What would I find in your camera bag?

In one bag you’d find three or four Holgas—some dedicated to lower-light situations, some for brighter or more “normal’ light—and a couple tabletop tripods, as well as flashlights and tape. In the other bag, carried alongside, you’d find a Mamiya6 medium format camera, loaded with color film, and a Canon 5ds-R with a 24-70mm lens, as well as a stobe and ringflash and extra batteries, cards and chargers.

What future plans do you have?

I’ve got four different projects in progress now, using all those different cameras I just mentioned. I work on them all side-by-side, and slowly chip away at the ambitions I have for each.

Finally, one last question. What opinion do you have of our print edition?

It’s lovely and very bold! The use of type is adventurous, and the display of the pictures dramatic. The heaviness and heft of the publication give is real “gravity”, as does the paper stock, which announces a real seriousness…