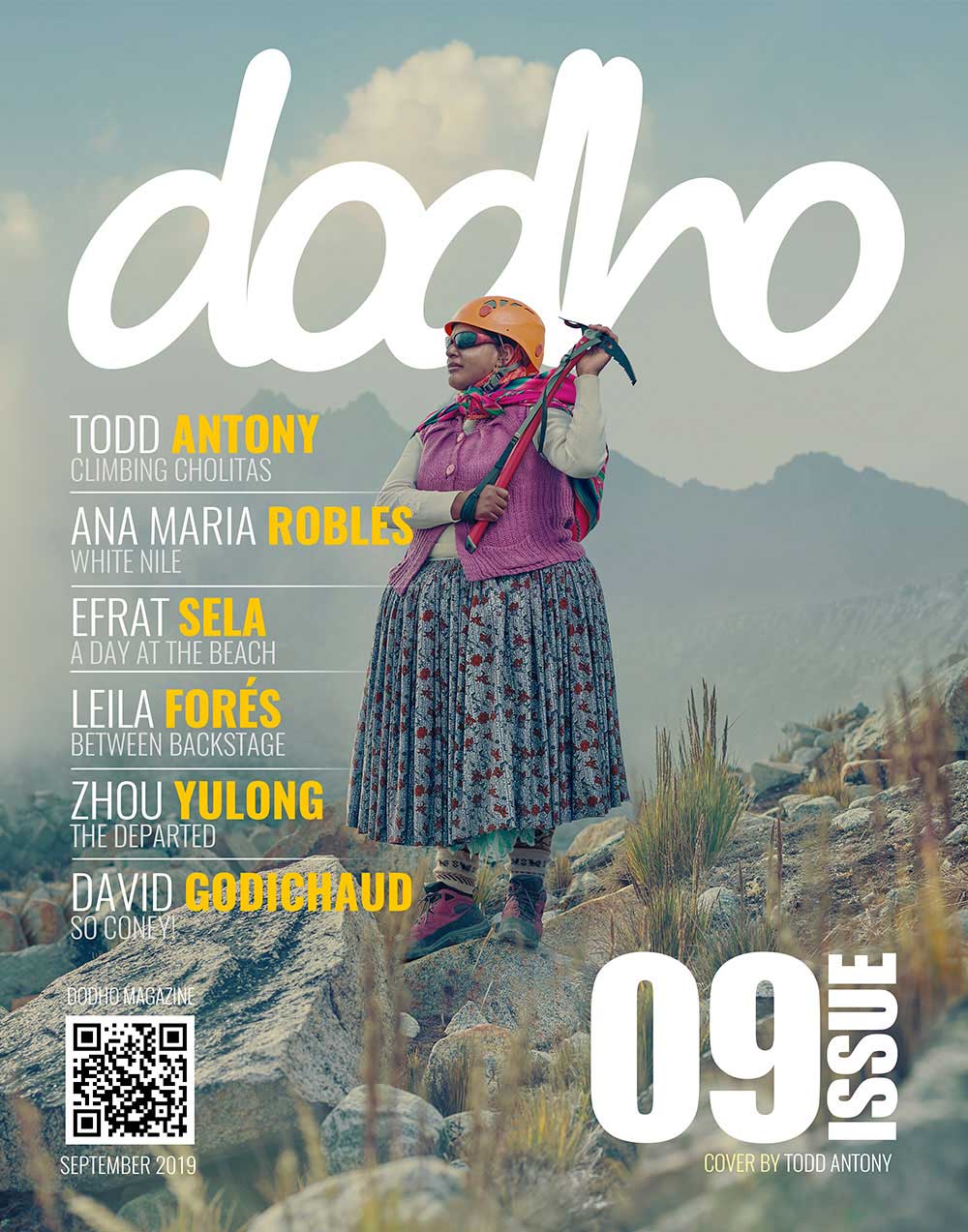

TODD ANTONY PUBLISHED IN OUR PRINT EDITION 09

TODD ANTONY PUBLISHED IN OUR PRINT EDITION 09

Born in New Zealand, based in London and shooting worldwide, Todd Antony is a multi-award winning photographer whose diverse skill set leads to some equally diverse commissions and personal projects.

He has been working as a photographer for 16 years and is represented in the UK, U.S. France and Australia. His work has featured in numerous awards, including the AOP Awards, Communication Arts Photo Annual, Creative Review Photo Awards, American Photography Awards, and has been included multiple times in Lurzerʼs Archive ‘200 Best Advertising Photographers Worldwideʼ. His work has been exhibited in London, the USA and France, and his commercial clients include amongst others, Samsung, Sony, Shell, Audi and the BBC. [Official Website]

What photograph would you say epitomises this experience for you when you look back at this body of work, and you reminisce on the potential friendship you had with these extraordinary women?

While it’s not my favourite image from the series photographically, it’s the one that conjures up the most personaI emotions and memories and the one that best epitomises the experience. The image of the 5 Cholitas standing shoulder to shoulder with their backs to camera, as they look out to Hauyna Potosi mountain in the distance. It was taken just after sunrise during the Pachamama ceremony on the first day with the anticipation of going up the mountain. Being part of the ceremony with the cholitas felt like we were being invited into their world. Standing in the freezing early morning air and calm, as we caught our first glimpse of Huayna Potosi, is such a visceral memory.

What I specifically love about “Climbing Cholitas”, are the portraitures of individual Cholitas. There interesting because they look like there meant to be staged but similarly have a really smooth and natural feel to them. Could you tell me a bit about how you came to capture these images? If you asked them during the climb, were they taken during the same day etc?

I knew in advance that I wanted to create the portraits, but the where and how element can only ever be tackled once you’re on location and found a spot that grabs you, and then you have to work with the weather that you are given on that day. With the portraits I wanted to create a slightly anthropological feel. Almost like the dioramas you see in museums with the painted backgrounds and perfect lighting. Before the climb I already had in mind for the backgrounds to hopefully have a degree of atmospheric haze or cloud to help with that effect, and give the images an almost painterly depth. On the first day on the mountain, it was quite clear so I shot a series of portraits using a slightly different lighting technique to account for the hard sunlight. (the portrait of Dora). Then on day 2, as we rounded a bend that reveals a view deep down into a valley below, I saw that cloud was being pushed up the valley and creating a wonderful diffused, textured light across the mountains in the background, and sometimes enveloping us in the process. I’m fairly sure I yelled out something with excitement as I saw what was happening, and stopped the group where we were to set up for some portraits. We had been planing to push straight on to the glacier that morning, but this light and weather was exactly what I had been hoping for in my perfect scenario, so we set up the camera and the flash to begin shooting. The flash is integral to the ‘smooth’ effect you mentioned. I needed to create an exposure where every element of the lighting was perfectly balanced between the backlit bright background, and the foreground where the cholitas faces would otherwise be in shadow without the use of the soft flash to balance them with the bright background.

The clothing in my opinion is quite an important factor when looking at these images. It contrasts quite nicely against the landscapes in which you were shooting. Is the clothing itself, specifically elements like the skirts and their colours native to this particular group of women in and around Bolivia?

Yes the beautiful contrast between the bright colourful clothing and the more monochromatic landscape was one of the things that initially grabbed my attention about them and got me excited about the prospect of shooting them, before diving in to research them further and discovering their rich backstory which only amplified my desire to shoot hem even more. The clothing is very unique to the Bolivian Cholitas. Although they’re not wearing them in these images, the bowler hats that they are synonymous for are primarily worn by Cholitas in the La Paz area, rather than the rest of the country.

Would you say that this journey to the summit of the mountain was almost like a spiritual reflection of the excommunication of Bolivia’s indigenous ‘Aymara’. And were you able to discuss this at any point during your journey?

Yes, definitely. Both parts of the project (the ‘Cholitas Escaladoras’ and the wrestling Cholitas) are both essentially about the Cholitas rise out of racial oppression and societal marginalisation. Their climbing is an almost literal symbolisation of their journey in life, and in the case of the wrestlers, their group was initially created partly for recreation and entertainment, but also as a way for women who had suffered domestic abuse to take out their frustration and stress. So their fighting becomes a mirror for both the struggle of the Aymara people as well as their own personal struggles. Since we had a lot of time with the Cholitas on the mountain, we were able to discuss it occasionally on easier parts of the climb and when resting together for lunch. Due to the lack of oxygen at that altitude, it actually becomes difficult to talk too much while you are walking!

Would you say that your involvement in wearing similar clothes, gear and participating in the “Pachamama offering ceremony”, are equally integral as the images that resulted from this. Do you believe that you wouldn’t have had images as successful if not for participating in this manner?

I think participating in those ways, those moments away from the camera, can only ever enhance the final images. It makes you feel closer to the subject on a personal level, and in turn makes them feel more comfortable with you also, which makes them feel more at ease with you when you’re shooting. For me it’s not just a case of going somewhere and taking some photos before hopping back on a plane again. It’s about the wider experience of the shoot, the journey. Getting to know people, experiencing. Things like the Pachamama ceremony are integral to that. It turns what is essentially quite an individual pursuit of taking photos, into a group effort and experience. We had an Apthapi (communal meal) each day on the mountain at lunchtime. Sitting at the base of the Zongo glacier eating together, with Huayna Potosi stretching up high above us is a moment I’ll always remember.

The idea of oxygen deprivation is something that we don’t experience until you have actually climbed a certain height. Did this hinder the way you shot or how you shot, and did you have to find alternate approaches to photographing your subjects?

The altitude was something that at the very initial stages of researching the project, I didn’t actually think about. It’s not a concern that you ordinarily consider when planning a shoot. When we are up mountains in Europe, it’s generally speaking not an issue, so it doesn’t jump into your mind at first. It was only once I delved deeper that I realised how high we would be and that it would play a large part. It definitely effected things from a planning point of view. We needed porters to carry our camera cases, as well as lighting equipment which isn’t something normally taken halfway up a mountain. It just wasn’t possible for us to take those ourselves and then have enough energy to climb where we needed to get to.

I still approached shooting in the same way as normal, but everything had to be slowed down quite a bit to compensate. Sometimes just moving around with the camera as I shot was enough to get me breathing heavily.

Thinking clearly about what you were wanting to achieve with a particular shot was also tricky at times. By the 2nd day myself and my assistant were suffering with pretty severe pounding headaches. We had a little oxygen on hand, but a few sucks on that would only ever clear your head for a couple of minutes. Your body is telling you pretty clearly that it doesn’t want to hang around up there too long.

Francesco Scalici

A recent MA graduate from the University of Lincoln, Francesco has now focused on landscape photography as the basis of his photographic platform. An author for DODHO magazine, Francesco’s interest in documentary photography has turned to writing and has had various articles, interviews and book reviews published on platforms such as: ‘All About Photo.com’, ‘Float Magazine’ and ‘Life Framer Magazine’. Currently on a photographic internship, Francesco has most recently been involved in the making of a short film titled: ‘No One Else’, directed by Pedro Sanchez Román and produced my Martin Nuza.