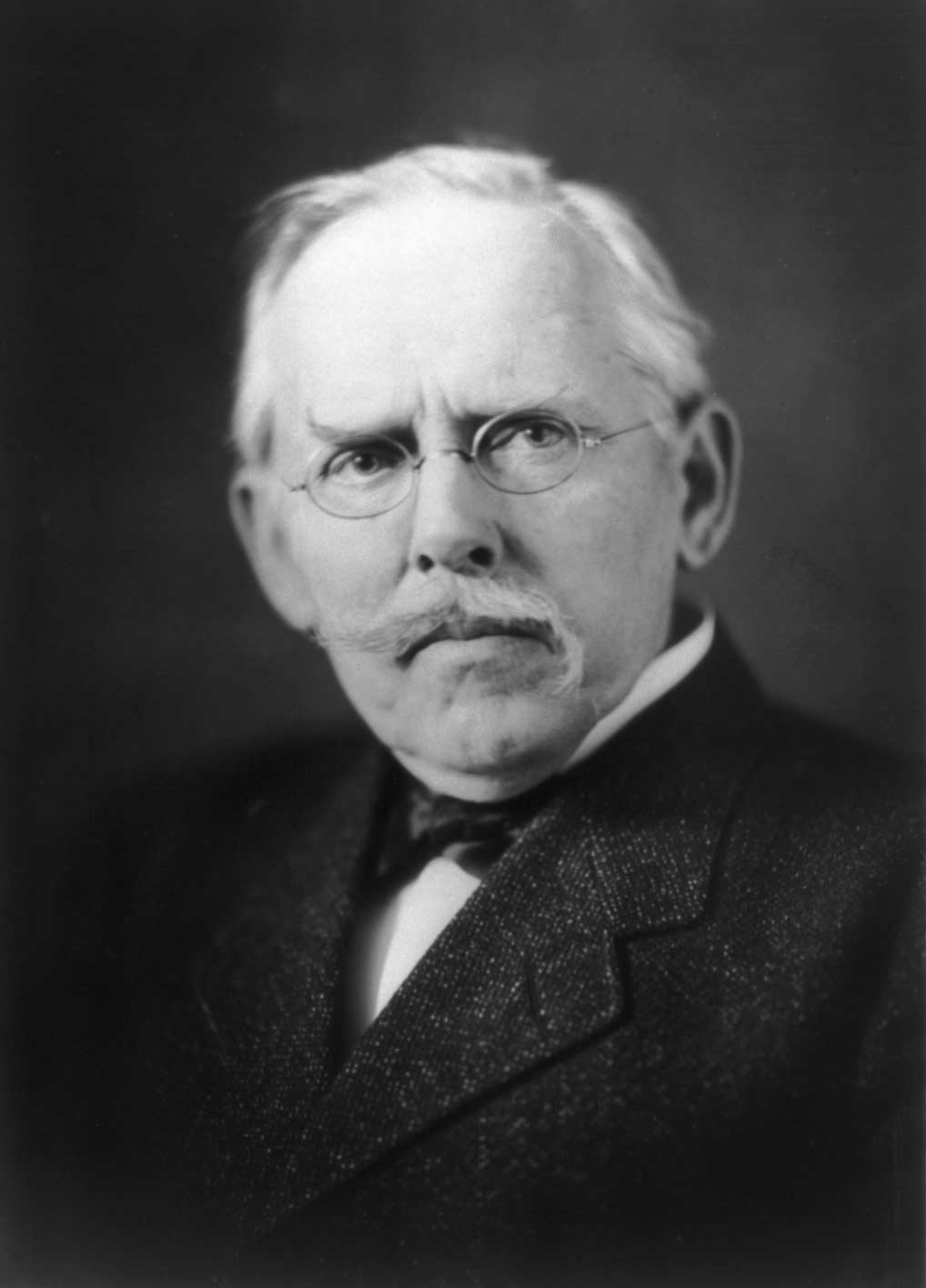

Jacob Riis, Famous for using his talent as a photographer and journalist to help the less fortunate in New York City, who were the main subjects of his works.

Jacob Riis captures a moment when the world, hidden by pretensions, presents itself without defense, photographing a restaurant that allowed you to sleep on the tables for only two cents. At other times, his images seek pose, seek emotional strength through the aestheticization of tragedy. They almost seem to seek a language that is never too raw and harsh, to allow a veiled vision to an audience that would reject the horror of reality.

Jacob August Riis was born on May 3, 1849, in Ribe, Denmark. He was the third of a family of 15 children, including an adopted sister. Despite his harshness, he had a reasonably happy childhood until he was seven, when a younger brother, Theodor, drowned.

His father wanted him to follow a literary career, but as a teenager, Jacob tried carpentry. At 16, he fell in love with Elisabeth Gjortz, daughter of the carpentry owner where he was an apprentice. Mr. Niels (his father) disapproved of both his son’s relationship and job and sent him to Copenhagen. After making a few carpenter’s nozzles in the capital for a few years, Jacob returned in 1868.

At 21, he emigrated to the United States through a somewhat laborious journey: in a small boat to Glasgow and in the third class of steamship Iowa to New York. He landed with only $40 in his pockets, and he spent half of that on the first day, buying a revolver.

After five days in poverty, he got a job as a carpenter in the Pittsburgh area. When he heard about the Franco-Prussian War, he tried to return (on foot) to New York and embark for Europe. He thought that maybe he could try to do a living as a mercenary.

“When nothing seems to help, I go look at a stonecutter hammering away at his rock perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred and first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not that blow that did it, but all that had gone before.”

Obviously, that idea did not work. Unable to find a stable job, he worked as a pawn, blacksmith, bricklayer, carpenter and salesman, and experienced the worst aspects of American urbanism – crime, disease, filth – in low-income and unhealthy housings, in dirty and dark alleys.

In 1874, he joined the South Brooklyn News (SBN), a newspaper that blatantly supported the Democratic party until the elections arrived and he was fired. Sometime later, he decided to buy the SBN and act as the editor, subeditor, distributor and ads searcher. He dedicated himself to raising issues of corrupted local policies, which doubled the sales of the newspaper.

In 1877, after selling the South Brooklyn News, getting married in Ribe, his hometown and returning to America, he got a job as a police reporter for the New York Tribune, covering some of the districts dominated by the city’s crime, a job that would lead him to fame and a friendship with the city governor, Theodore Roosevelt.

looking to multiply his lectures, exhibitions and publishing articles, he announced the terrible conditions in which entire families lived. Instead of being dazzled by the richness of America, he focused his lens on the forgotten corners of the Belle Époque: dirty and dark alleys, the thieves and members of gangs, abandoned old people and European immigrants who discovered that New World wasn’t really a land of opportunity.

“I’d look at one of my stonecutters hammering away at the rock, perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet, at the hundred and first blow it would split in two, and I knew it was not that blow that did it, but all that had gone before.”

Riis was not a professional photographer, but he learnt as he photographed. He never took into account neither the frames nor the light, or if there were characters that could distort the image. The use of the magnesium flash allowed him to shed light on alleys and scenes that went completely unnoticed by society.

While Alfred Stieglitz dedicated himself to photograph the changes that New York City was experiencing, always looking up as skyscrapers grew, Jacob looked down and discovered a parallel world that coexisted with the excessive growth of capitalism. Basically, the growth of the United States entailed other dire consequences for the population.

That was reflected in the book he published in 1890 ‘How the Other Half Lives’, a collection of photographs that show the social inequalities of the most cosmopolitan city of the moment.

Over the course of three years, Riis spent most of his nights photographing the New York underworld and its tenements. By this time, he was already beginning to attract attention as a social activist. In 1895, he was sought after by none other than Theodore Roosevelt, who, impressed by his book, promoted important social reforms as he began his career as a public security secretary.

He was one of the first in America to use a magnesium powder flash. He himself, with his partner Henry G. Piffard, had modified the formula invented in Germany in 1887, to make it less dangerous.

Riis died on his Massachusetts farm on May 26, 1914.