One perceives the world through the manifold of the senses and vision constitutes a fundamental way in which we process this world.

Our individual interpretations of the visual experience provide unique perceptions for each of us. Not everyone pays attention to the same thing and it is what people choose to look at that is the variable of life.

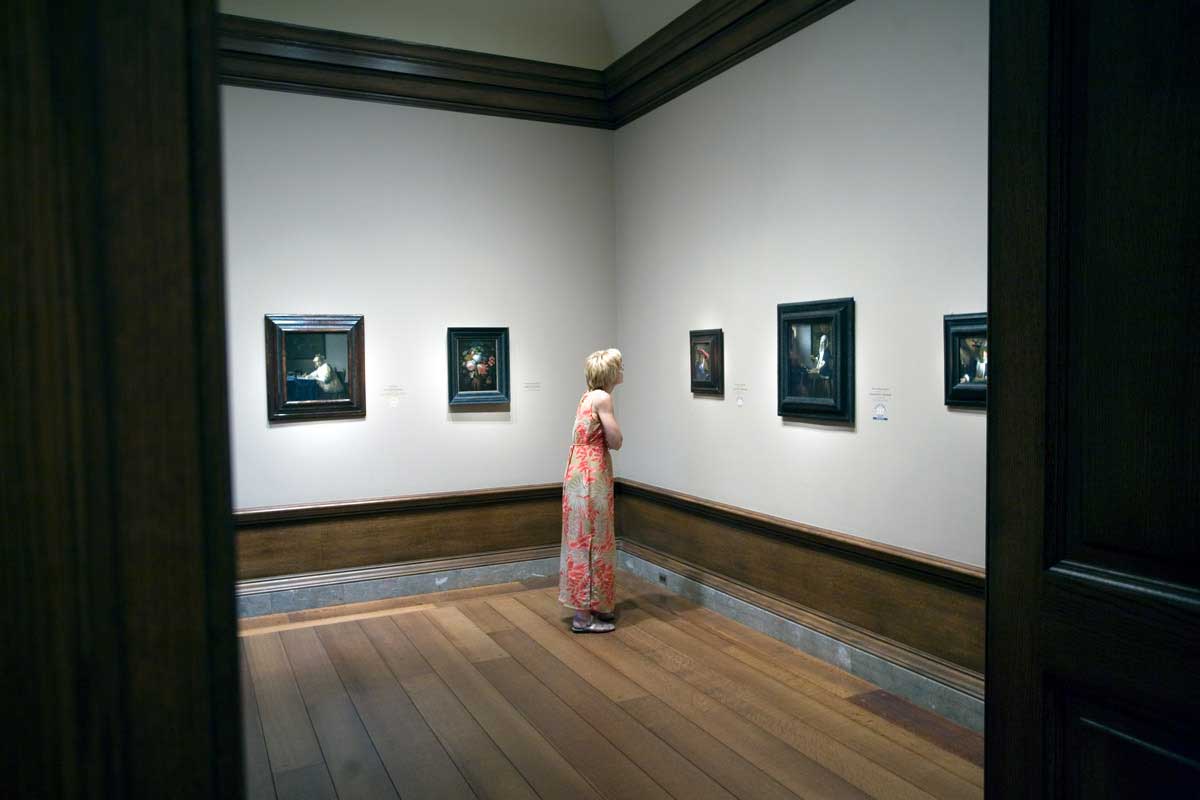

As a photographer Max Hirshfeld takes on the role of looking for us, through his lens he directs us. In his series “Looking at Looking”, Hirshfeld presents the narrative of people looking at art. Looking may seem like such a simple act, however Hirshfeld reveals its depth and complexity.

Hirshfeld brilliantly moves through the structured space of the museum as Winogrand moved through the streets of America. He brings the serendipity of street photography inside, using the snapshot aesthetic to portray a sense of realism. The seeming casualness to his photographs is actually quite calculated and his anticipated spontaneity enables Hirshfeld to create this narrative of looking. His decisive moments capture not the art but the state of mind of his museum subjects engaged in looking and in thought. He visually records that intangible internal moment — the internal dialogue of subject to object, viewer to art — and makes it an eternal moment.

A museum is the quintessential milieu in which to observe this element of human existence. In the simplest terms, a museum exists to collect, to preserve and to present objects for visitors to look at and experience. The audience is limited to just looking and there is a certain etiquette in looking — not too close and definitely no touching. This perpetuates an often-humorous dance of the viewer around the artwork.

Hirshfeld captures a diversity of viewers and their interplay of looking as they move through the vast selection of artwork. Visitors peruse, stop at one painting, pass by another, linger, and even photograph the works of art. Hirshfeld is not the only one in the museum with a camera, yet his intent is not to focus on the artwork. This fact enables Hirshfeld the freedom to photograph and to go unnoticed in his looking. Cleverly Hirshfeld suggests that he may not be the only one looking at visitors looking. The portrait by Cezanne peers down upon the museum visitor who looks off to the left, focused on something out of the frame. The subjects in the art on the museum walls look at the museum-goers, even if the visitor decides not to look.

The people in the museum assume the paintings and sculptures are on display. But they are objects on display in Hirshfeld’s photographs. There is a false sense of privacy inherent in public space. Take, for example, the young couple comfortably consumed by Pissarro’s painting of Paris. They embrace each other and share a tender moment together. Unknowingly, the moment is shared with Hirshfeld as well.

Hirshfeld too is consumed by his own looking. Within a zone of controlled creativity and improvisation, he orchestrates harmony out of a continuous cacophony of movement. To use a term suggested by William S. Burroughs, Hirshfeld is the “creative observer” who points out fleeting connections of offbeat harmony:

Nothing exists until or unless it is observed. An artist is making something exist by observing it. And his hope for other people is that they will also make it exist by observing it. I call it ‘creative observation.

This creative observation by Hirshfeld threads together a unique and playful vision. As a jazz musician who expresses melody in an atonal scale, Hirshfeld synthesizes his lens of perception and interpretation.

Hirshfeld also plays with the idea that art is a commodity up for consumption. Just looking is sometimes not enough for these museum-goers. They often relate to the artwork by photographing it themselves. In plate #30, a father snaps a photo of his son in front of a Pollock painting seemingly not even getting the whole painting in the camera frame but rather creating an abstract background in which to frame his son. What is the father’s intent? Does photographing the art make it more accessible? Is it proof of having been there and seen it? Does the photo of the artwork represent the real thing? Or is it less about the artwork and more about obtaining and remembering the moment, the moment of being there, the moment of looking?

It is this moment of looking, connecting and experiencing on whatever level and in whatever way that Hirshfeld showcases in his work. Now as you view these photographs in the intimate space of this book or within the public space of a gallery you mirror the viewers looking at art in Hirshfeld’s photographs. As you look are you conscious of your own looking? Or does the object on which you are focused consume your consciousness? If for a moment you refocus on what you are doing instead of what you are looking at, you may realize you cannot concentrate on both at the same time. Sartre would suggest in Being and Nothingness, that you can never really capture your own act of capturing. You may have a mystical awareness of your consciousness but it forever flees from objective grasp. Hirshfeld succeeds in glancing at that moment in which a person’s consciousness joins with its object. He exposes the self immersed in experience and ultimately his work may lead us to contemplate that which we never see: our own act of looking. [Text: Larissa Leclair]

About Max Hirshfeld

Max grew up in a house full of books and music, to parents who survived the Holocaust and ended up settling in small-town Alabama. His father, a child prodigy who first performed with The Warsaw Philharmonic, prodded Max to embrace the arts and suffused their home with the curiosity born of generations of rigorous intellectual and artistic pursuits.

Six years as a staff photographer with The Smithsonian Institution and a career-altering week at the University of Missouri photojournalism workshop in 1977 propelled Max into over fifteen years of commercial photography before a trip to Poland (accompanying his mother on her first return in 46 years) gave him a new appreciation for the power of photography and added a new dimension to his work.

Max’s images show a strong respect for the great traditions of documentary photography wedded to a deep love of humanity. Over thirty years of advertising and editorial photography in the studio and on location coupled with his vibrant yet emotional personal work has made Max one of the best photographers working today. His work has been featured in Rolling Stone, GQ, Time, Forbes and Vanity Fair and in advertising campaigns for Amtrak, Johnson & Johnson, Ikea and The US Mint. [Official Website]