I have never seen dead bodies piled up by the side of the road before. Bodies like rice dropped from a bag. Mothers looking for their daughters, adamant that they must be there, even two weeks after the collapse.

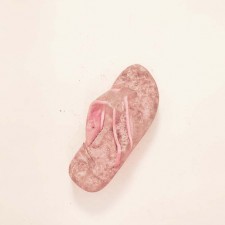

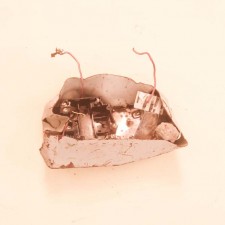

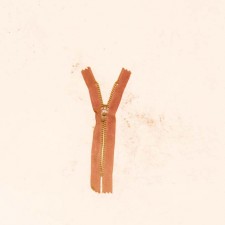

More than 1,135 souls. Missing. I also returned for weeks, not completely sure why. I hadn’t known anyone there, nor was I an activist for garment factory worker’s rights. But I had to be there. Almost half as many had died from the Rana Plaza collapse, as those did in the World Trade Center. The footprint of the building was no larger than a basketball court. The Twin Towers covered 16 acres. I wandered around the wreckage and came across human hair, purses, under garments, an odd tea pot, gloves manufactured for export, broken machines and damaged manikins.

I started collecting them.

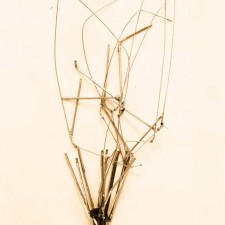

A sense of responsibility stirred within me. I cannot fully explain it. It was later described to me as trauma. The found objects piled up in my room, bringing with them the smell of rotten flesh, the smell of Rana plaza. Many of them had blood of the victims. They stayed with me for about six months; I slept in the same room with them. After two weeks of searching, the government had put up an eight feet high fence around the perimeter, hiding the site from family members desperately in search of their loved ones. All that remained of the site was a shallow pit, partially covered in pre-monsoon waters. About six months after the collapse, I started photographing the objects I had collected. I did not want to see pictures of the destruction and death any more, but I never wanted to forget. I felt disgusted when others complimented me for my photographs of the destruction.

I had long hair that I had planned on growing even longer. But sadness overtook me and I soon parted with my locks. There was a smell all over my hair, an imaginary smell of dead flesh. I kept my cut hair too, along with the hair I had found at the site.

About Atish Saha

Atish Saha born 1990, a Dhaka based documentary photographer currently student of Pathshala South Asian Media Academy. In 2011, he joined Pathshala to study documentary photography. Since then, his prime arena of interest is socio-political and cultural at the same time fictional documentaries. His topical works illuminate the numerous questions of garment manufacturing and communal attack in Bangladesh.

His works have appeared in Time, The Guardian, many others international and local media.