The photography of the 21st century is still able to surprise us. The mass of images that land on our screens every day is so enormous that twenty-four hours would probably not be enough to count them.

We live not so much in the excess of images but in their constant storm. We are not even allowed to take a breath from them, to create image-free shelters for ourselves or build indestructible fortifications. So how are we supposed to perceive reality, to say nothing of living in the visual apocalypse of our day?

On the one hand, today’s mass media engulfs us into rituals of insatiable consumption (when spending hours on Instagram, Facebook, or pointlessly browsing news portals we are being forced to re-identify with the grimaces of reality popping up in the stream of images); on the other hand, by finding ourselves in an intense visual flow, we at the same time become hostages to the dilemma – i.e. we are pressed to decide fairly quickly which image we shall pay our attention to and how much of it (the resolving of this dilemma also depends on our aesthetic taste). The dilemma is a challenge to every artist as well, for they must develop a unique artistic language with much more care, patience, and subtlety, striving for public attention and taking root in the continually accelerating image culture.

Some artists, however, do not seek to strictly follow the fashions of visual culture while competing on the common visual-informational highway. Like Buddhist monks, they work patiently, concentrating on their every creative gesture. Such artists are quite strong and diligent personalities. Having discovered them in these times of mediocrity the world, entrapped in the continuous flow of images, pauses in awe: is such authenticity still possible? Probably that is why I am still fascinated and continually amazed by the photographer Žilvinas Kropas who lives in Panevėžys. Recently his works have received quite a lot of recognition not only in Lithuania, but also abroad. For many years, the artist has been patiently developing his subtle artistic program and is persistently following his unique artistic path.

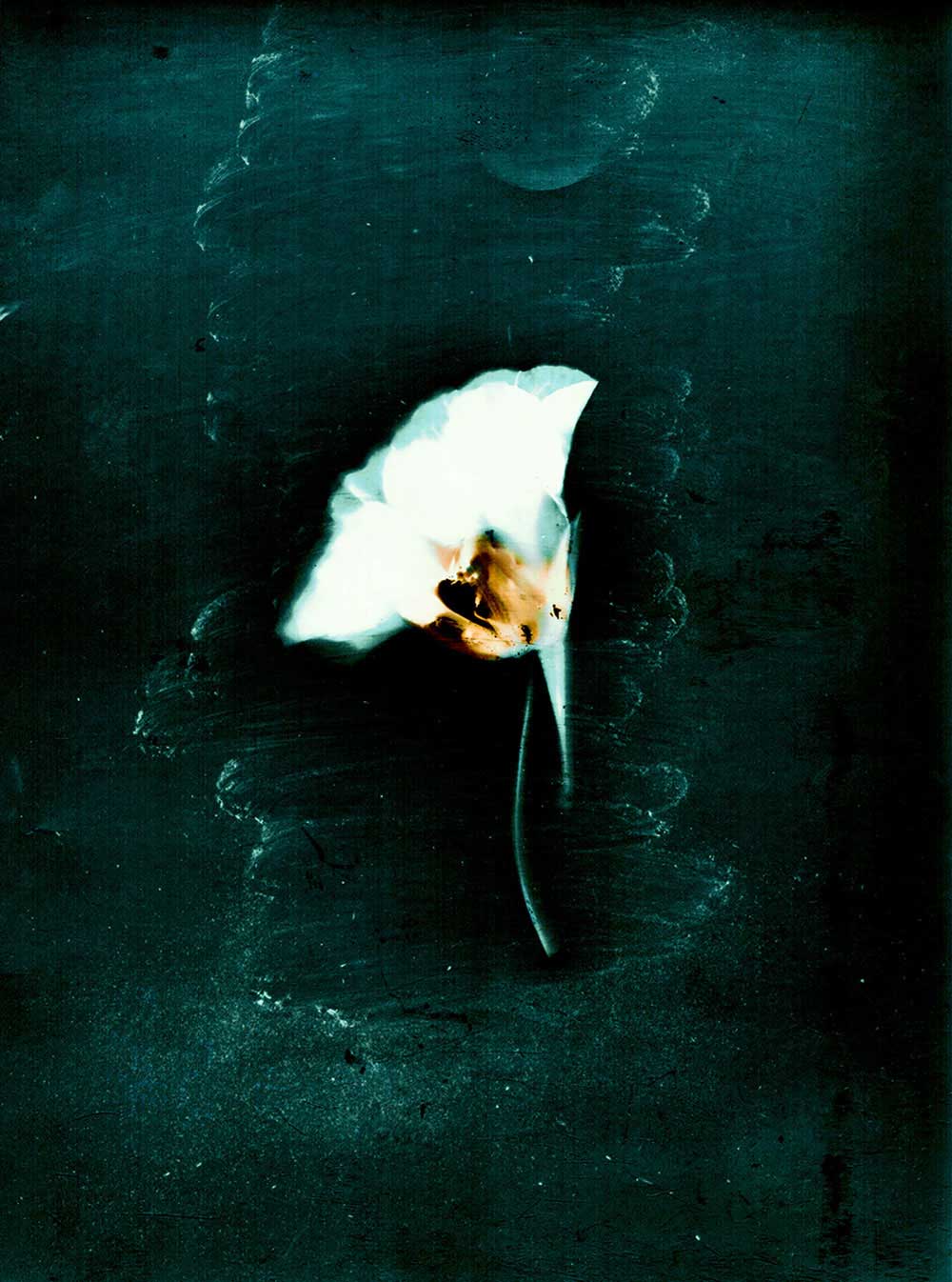

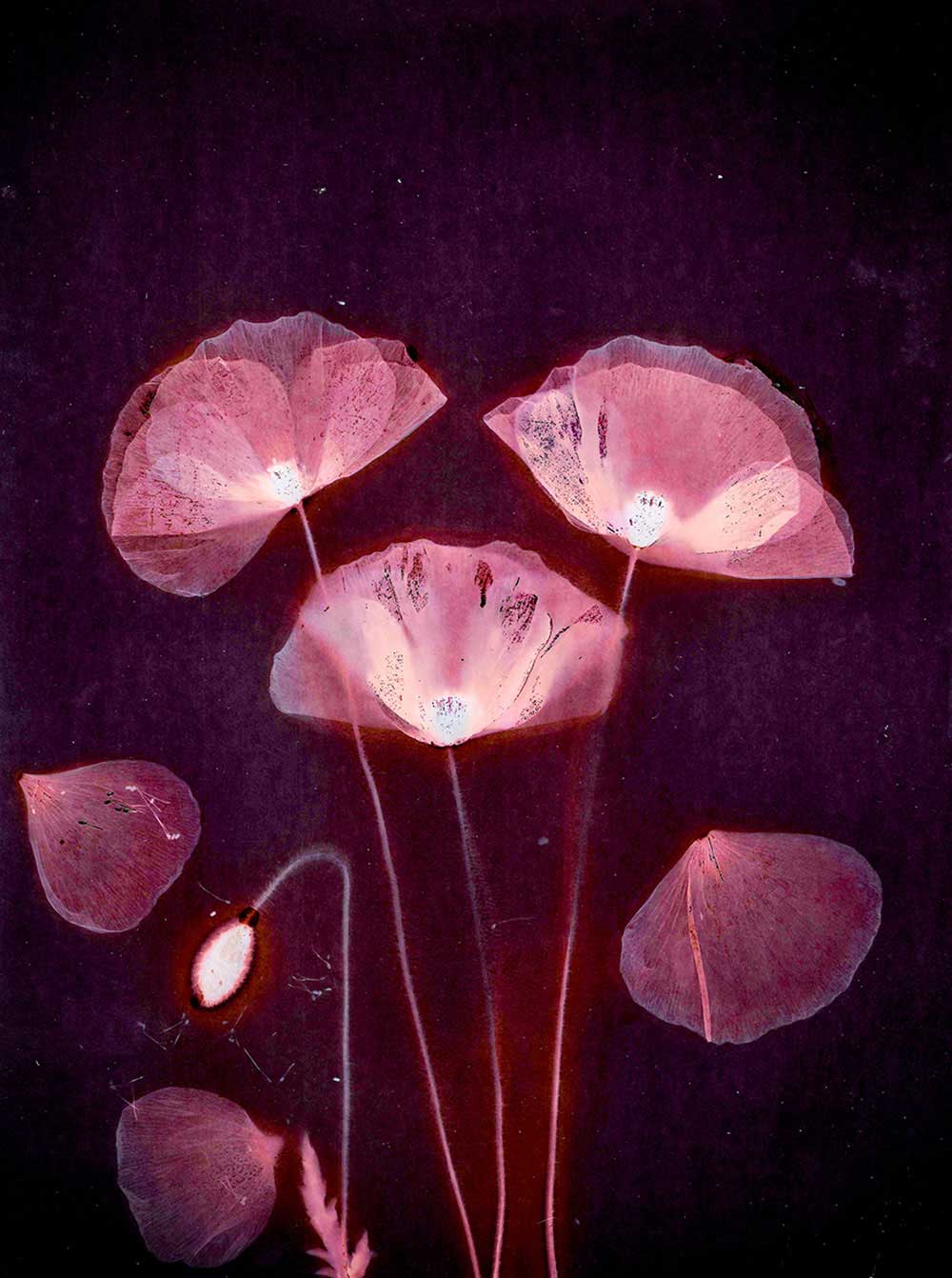

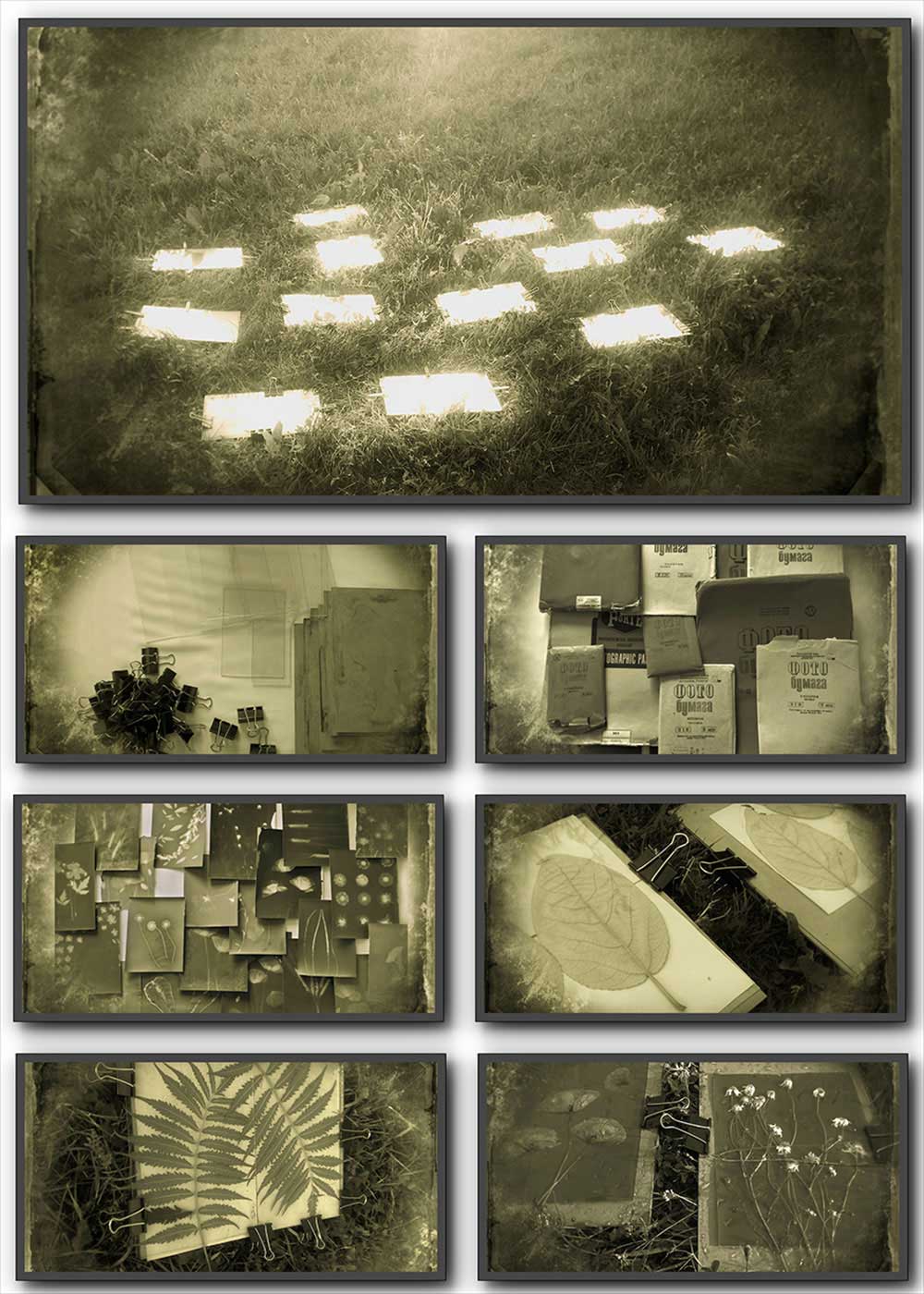

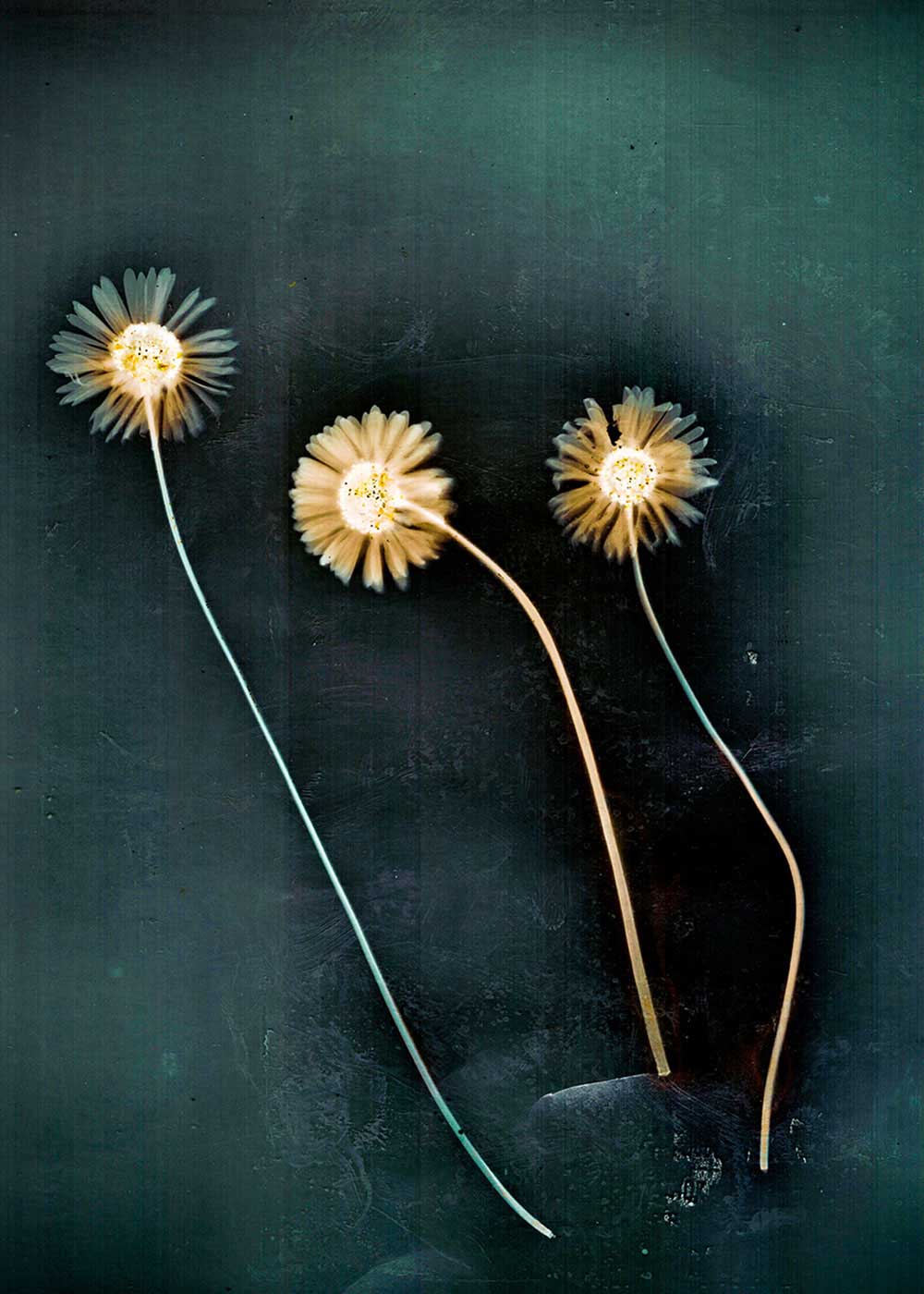

It may seem that it is the path of the classics. Žilvinas Kropas is looking for an opportunity to capture the rays of the sun in a light-sensitive material and thus record the world in a rather limited print. The images created by the artist appeal to the artistic tradition of pictoriality. Žilvinas Kropas also shows us that no matter how old the creative approaches (old technologies, themes, creative motives, challenges of artistic legitimacy) are, they can still be original and significant against the background of today’s visual noise.

Probably the majority of viewers looking at Kropas’ work always want to ask about how the technology he applies is developed, how one or another imprint of an object found in the everyday world is obtained. In displaying the prints, the artist himself tells us about the depiction of reality, and about the recording of that reality as well. I.e. his visual solutions raise questions of birth, creation, development of language. In this way, the artist seems to interpret the conceptual approach towards writing practiced by Jacques Derrida (1930 – 2004), a representative of French poststructuralist philosophy.

In the work of Kropas, the intertextual and intervisual image, imprinted and demonstrated on a flat surface, is equated to writing. The image represents the world, but also emphasizes the target (re)presentation strategy that depends on the historical situation and tradition. Not always easy to remember, rather abstract forms reveal intervisual connections, allowing to liken the process of image creation to the invention of a writing act which tries to find and bring to life previous depictions / writings. As Derrida would say, with this rather complicated creative gesture, the artist moves towards arche-writing (i.e. the nature of the writing itself).

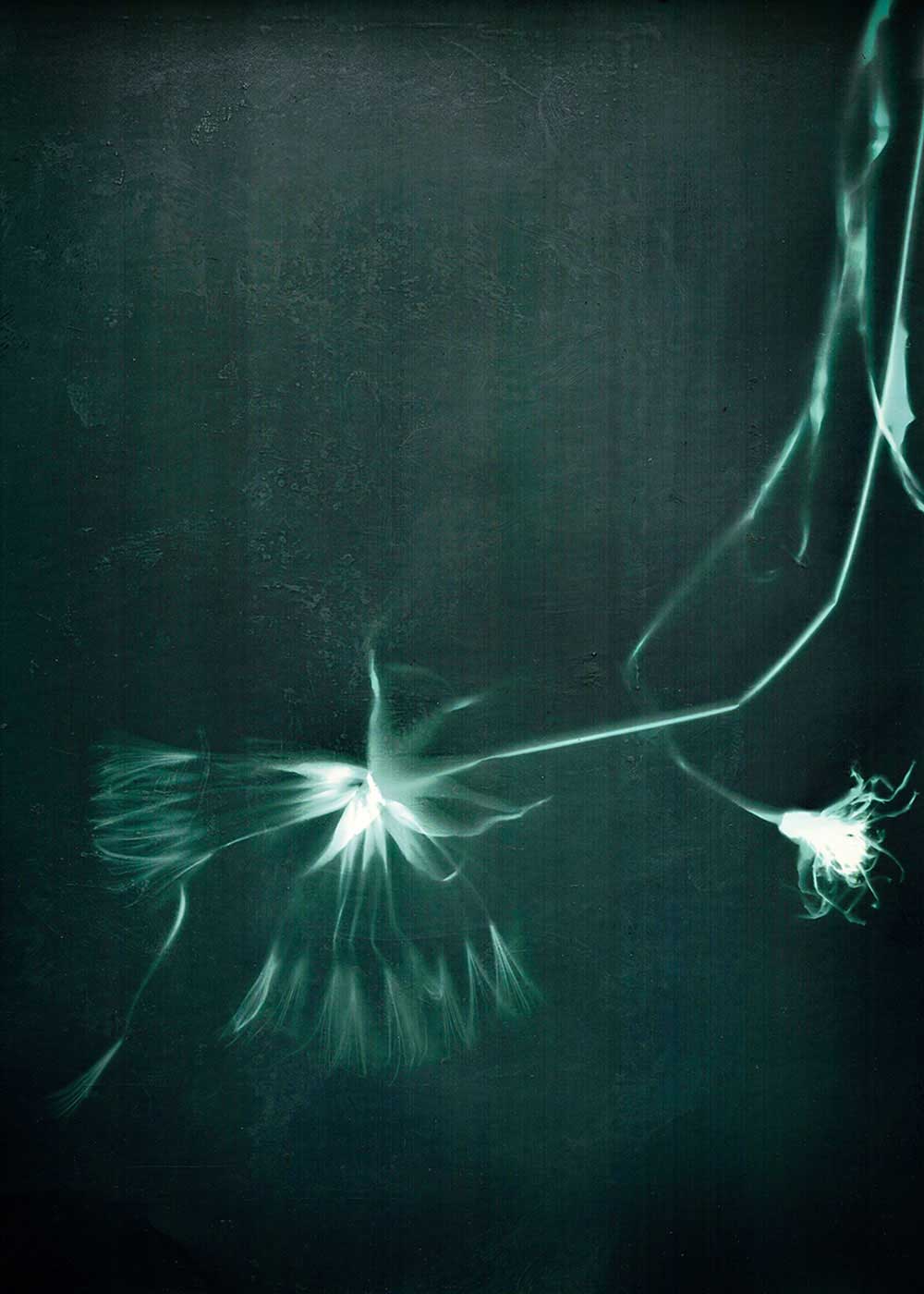

When photography is discussed as writing, then the gesture of photographic creation moves towards writing, which is actualized by Derrida’s works On Grammatology (1967) and Truth in Painting (1978). Consequently, when the parallels between philosophical discourse and photographic imprint open up in explaining the problem of writing as medium and writing as process, when drawing with light (meaning of the term ‘photography’, R. V. note) is compared to writing as process, then it is possible to discuss even the relationship between logos and language and the position of logos in visual culture.

The Greek logos stands for reason, the world, and vocally expressed language. The more abstract the drawing with light becomes, the more it tries to withdraw from the zone of violence inherent in logos (reason). Unfortunately, the recognizable shapes in the photos bring us back to language, i.e. the logos sphere of influence. Eventually, it becomes clear that photography is a power game with logos, but not a withdrawal from it. It is this grapple that makes the photography of Kropas a rather interesting phenomenon that raises some doubts about the concept of an image as capable of telling the truth. In the case of Kropas artwork, one gets the impression that the artist has concealed something, that something was left hidden and is still waiting to be discovered and exposed.

This situation is solved through the dialogue of abstract images and forms of reality. Understanding of abstract images is usually lacking or their history is not revealed but concealed. In this case, history is what helps to name the identity of photography. Still, with his images, Žilvinas Kropas encourages disregard for logocentrism and the destruction of the established language of images as a multiple copy of copies – as a language of languages that falsely reveals the world. However, discovering pure references to recognizable forms in abstract images and recognizing the experiences of the tactile and visual worlds briefly activates the logos itself. The artist’s struggle with the traditional forms of portrayal and the pursuit of his unique artistic language has no end and is created as an ever-changing cycle. [Text by Prof. Dr. Remigijus Venckus | Media artist and critic]