In the last decades, the landscapes of the Arab Gulf region have undergone a mutation driven by increased income from the oil, globalization and mass tourism.

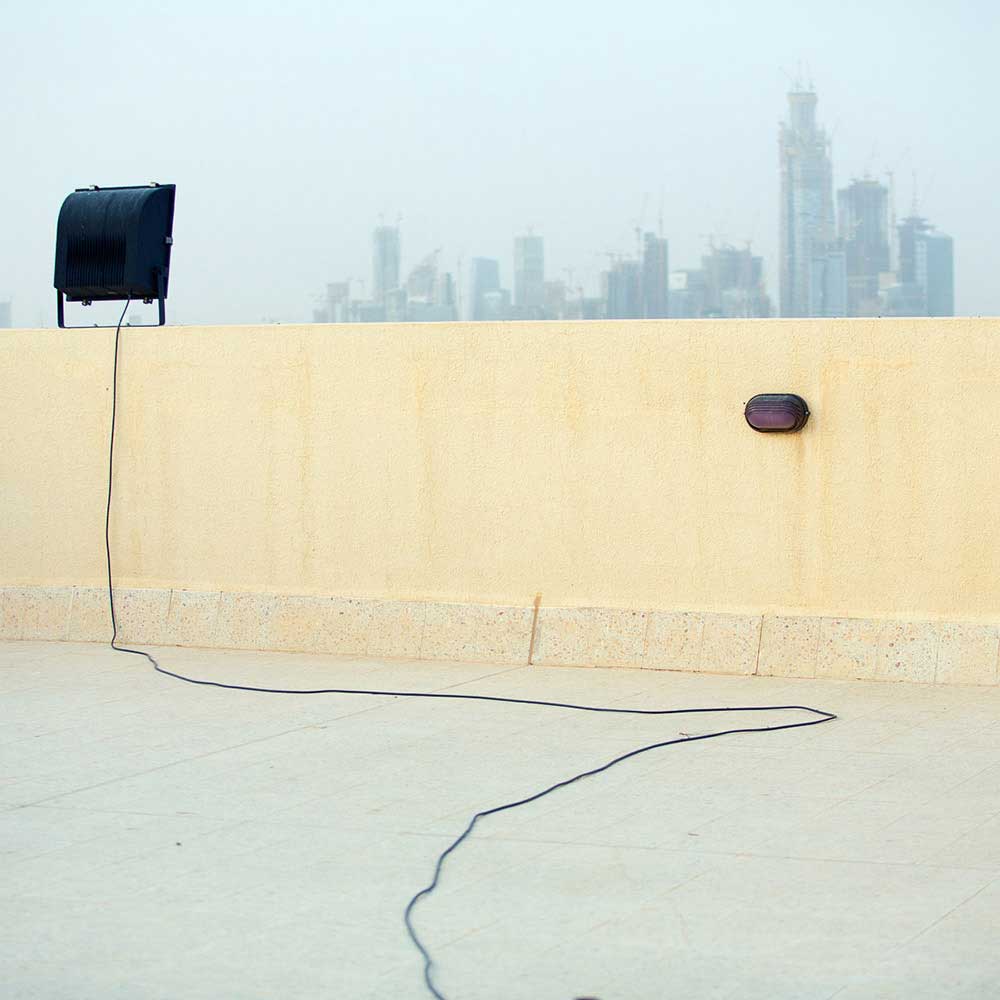

These countries have seen a huge transformation, moving from the nomadic, traditional and austere lifestyle of the desert bedouins to a postmodern, urban and consumerist society. ‘Min Turab’, that takes its title from an arabic expression meaning “from the land”, holds up a mirror to the dyad of nature and technology in a place where the old and the new come together and the lines between them blur completely.

Although this itinerary may be somehow reminiscent of the 19th-century grand tour, in Min Turab the attention is not focused to the most popular sites of photographic pilgrimage but in the opposite direction. The areas to study point to the newest centers of unbridled urban development with an approach from the outskirts, the periphery, and the back alley. ‘Min Turab’ steps back a few miles and takes in his secondary, less privileged view, addressing towards the ‘small’. Apparently anecdotal details, at least in this case, end up being the most meaningful of all. Taken together, the project, developed from 2009 until 2017 calmly scrutinize the exact places where landscape alteration, linked to oil as a main agent of change, has produced a fatal discord, a sort of friction that destroys earlier visions and ideas of a place: the notions that we might have as uninformed foreign spectators, or that locals might have as they deal with landscapes transforming rapidly before their eyes—landscapes that, for the first time in history, they will outlive.

Min Turab also has important geopolitical implications. What would scarcely be remarkable in a Western city is scandalous and fascinating in equal measure to foreigners visiting places like Riyadh, Doha and Dubai. It is hard to resist criticizing the overwhelming deployment of technology only to escape to the equally atrocious spectacle of globalization in countries other than our own.

If the classic conception of landscape, which many of today’s photographic projects have inherited, helped naturalize the ideology of unequal social relationships and disguised the reality of the historic conflict implied therein, then the challenges that current photography must face when reflecting on an increasingly complex landscape are clear. That does not mean, however, that they will be at all easy to address. Perhaps, by identifying the blind spots where waves of images are being swept away and replaced by others of a very different sort, Min Turab allows us to confront this new visual regime that imposes the conditions of hyper-visibility of some landscapes and the dramatic dismissal of others. [Official Website]