I learned to photograph at the Savonese Photographic Circle, in 1983 in Savona. Every Friday evening, in a dilapidated place, 15-20 people passionate about photography gathered.

Those who wanted to share their images leaned their prints against a slightly inclined wall and exhibited there, in addition to the images, also their soul. Sometimes that wall became a grill, often a cross, but I still remember the criticisms and the precious advice of the partners. As we grew up the observations went from good-natured to increasingly severe, as is right. Everyone said what they thought but you had to be able to distinguish between the praises of the “enemies” who, in order not to improve you, complimented you when you took bad photographs, the constructive criticisms of friends who cared about your growth and the ferocity of the envious who they couldn’t imitate you.

This was my photography school. I still remember the precious advice of the President of the Club, Valentino Torello, who had a pastry shop in the center and of Ottavio Caligaris who ran a newsagent in the city. They were great teachers for me, especially Ottavio, whom I took to see the first auditions in the narrow cabin of his newsstand. I called it “The Confessional” because often the discussion on images also extended to private life. It is not possible otherwise if you use photography as a means of expressing your soul.

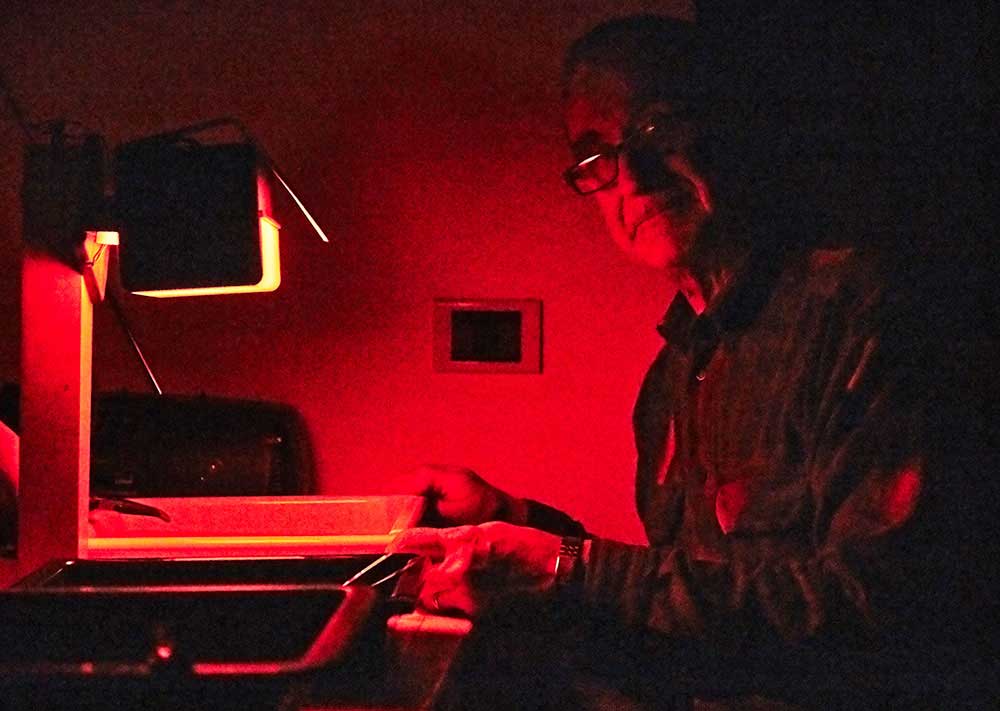

I started producing B&W prints: developing the film in the Paterson tank, printing with the enlarger and developing in the bowl under the red light. A magic that made the heart jump when the image began to appear in the tray. But the problem was being able to understand how to choose the infinite gradations of contrast of the paper and my prints, subjected to the judgment of the experts of the Circle, never went well. I was so disheartened that I thought I’d quit when meeting a great friend not only saved me but even reconverted my passion.

Igino Pizzetti, one of the heads of the analysis laboratory of the Ferrania plant where we worked, and I had become friends. We met for a year in my laboratory during the lunch break. We worked every day on a project to produce a home developer for the slides.

Pizzetti, a man of, rare, brilliant intelligence, was printing color photographs as early as 1955 using seven rigidly thermostated baths, a thing of crazy difficulty!

One day, given my passion, he generously decided to pass on his experience of him and to teach me to print from color negative. When I took Ottavio to see the first color tests he seemed mad with joy and he started screaming calling all the friends nearby to come and see. It was the first time that my photographic destiny changed direction.

I had become a colorist in a club of black and white players. I later discovered that they too were not satisfied with the B&W and had many attempted to print in color without success. I felt palpable the esteem and envy that had been created towards me. The pictorial taste derived from my past facilitated the task but the winning weapon was above all one: the color paper had only one degree of contrast. So you didn’t have to choose, having too many choices, instead of being an advantage, it had turned into a double-edged sword for me. You just had to make the most of what was available and that was my specialty, the continuous development of creativity beyond technique.

Since then, before going to Ottavio’s, I used to pass by Pizzetti who, with his infallible eye, helped me in the difficult task of recognizing the dominant colors of the prints and the way to neutralize them to obtain the desired result.

It could happen that I spend a whole night producing a single image and then, satisfied with the result, go the next morning to show it to Pizzetti who might say to me: “Nice, good, but he’s a little blue”. Since he said it too I realized that, indeed, the image had an unbearable cold cast. So I learned how to build the sensitivity of my eye. Since then I have started to use dominants at my leisure, as an extra chance, to reinforce emotions and introduce sensations. My prints highlighted the manual skills and took on a particular tone that made them immediately recognizable, personal, very different from all other photographers.

It was Igino Pizzetti again who gave me gelatin filters of different shades in yellow, magenta and cyan that I slipped into the filter holder of a B / W enlarger to be able to print in color. Later I also bought a Durst enlarger with a color head but even today those gelatin sheets, which were a treasure when I used them, I jealously keep them as the tangible legacy of my master even if they are no longer of any practical use.

At the Savonese Photographic Circle they had taught me to express myself through series of images, such as a portfolio, an exhibition, rather than saying everything with a single photograph. Thus was born my first series themed ships.

The small distant ships that I saw on the horizon inside and outside of me in my interminable, solitary walks by the sea. I began to participate in competitions first at the local level and then higher and higher, nationally and internationally.

“Awarded 50 times of which 30 as the absolute best author on all sections” is written in my curriculum.

This reminds me of my fencing master, Captain Antonio Ascione who, although a very good fencer, had never won a competition. He used to say with his nice Neapolitan accent: “The satisfactions that fencing did not give me was given to me by bridge”.

In fact, he was a high-level champion of what is perhaps the best game in the world. My fate was similar in the sense that based on my commitment to sport, practiced intensely with great passion for 25 years, my booty was miserable. I would have liked to win a cup in a race but I have never been able to fulfill this dream. The year of greatest success I finished sixth in the Italian championships. There were cups up to fifth place … in sixth a plaque!

When, on the other hand, I dedicated myself to photographic competitions, I won so many cups that some, not knowing where to place them at home, I had to throw away. So I too was able to say: “The satisfactions that fencing did not give me was given to me by photography”.

GiBi Peluffo

I did a lot of things in my career as an amateur before and as a professional after. From travel reports, to news, sports, current events but, given my vocation, I would like to be remembered as a humanitarian photographer. I worked for Emergency in Sierra Leone, Cambodia, Sudan and the Central African Republic. For Unicef in the Republic of Moldova, for the Children's Rights Forum of Chernobyl in Belarus and for the Carmelite Fathers of the Infant Jesus of Prague in the Central African Republic. Currently I perform studio portraits, wedding services, ballet in the theater, shows, advertising and tourism promotion for companies and municipalities. I take valuable photos of different genres dedicated to the production of websites for companies. Since 1994 I have continued to offer my personal photographic course which teaches how to see photographically.