Today palm oil is seen as a substance to be avoided in food uses due to its high percentage of saturated fats, but in Africa this condiment is instead widely used and appreciated.

It is due to the initiative and perseverance of a man that this oil is produced at the Mission of Mount Carmel in Bangui. A man capable of changing a fruitless forest to rebuild it full of different plants useful to people. It is in fact, thanks to the initiative of Father Anastasio that we owe that wonderful view that can be enjoyed climbing the hill leading to the friars’ convent: a plantation of over ten thousand oil palms planted in recent years.

Each plant produces several clusters of dates which, black when unripe, turn orange red at the end of ripening. They are then collected and processed with an almost completely manual process to produce a reddish and viscous oil with an intense flavor. Today rudimentary machines are used, but for part of the work, the favorite tool remains the machete. It is a long and heavy cutlass that in Africa is responsible for many massacres and mutilations, but which here, fortunately, is used only as a tool. After cleaning, the dates are steamed in a large tank until they soften and begin to exude oil. Subsequently a screw press squeezes the pulp producing crude oil which is collected in a basin.

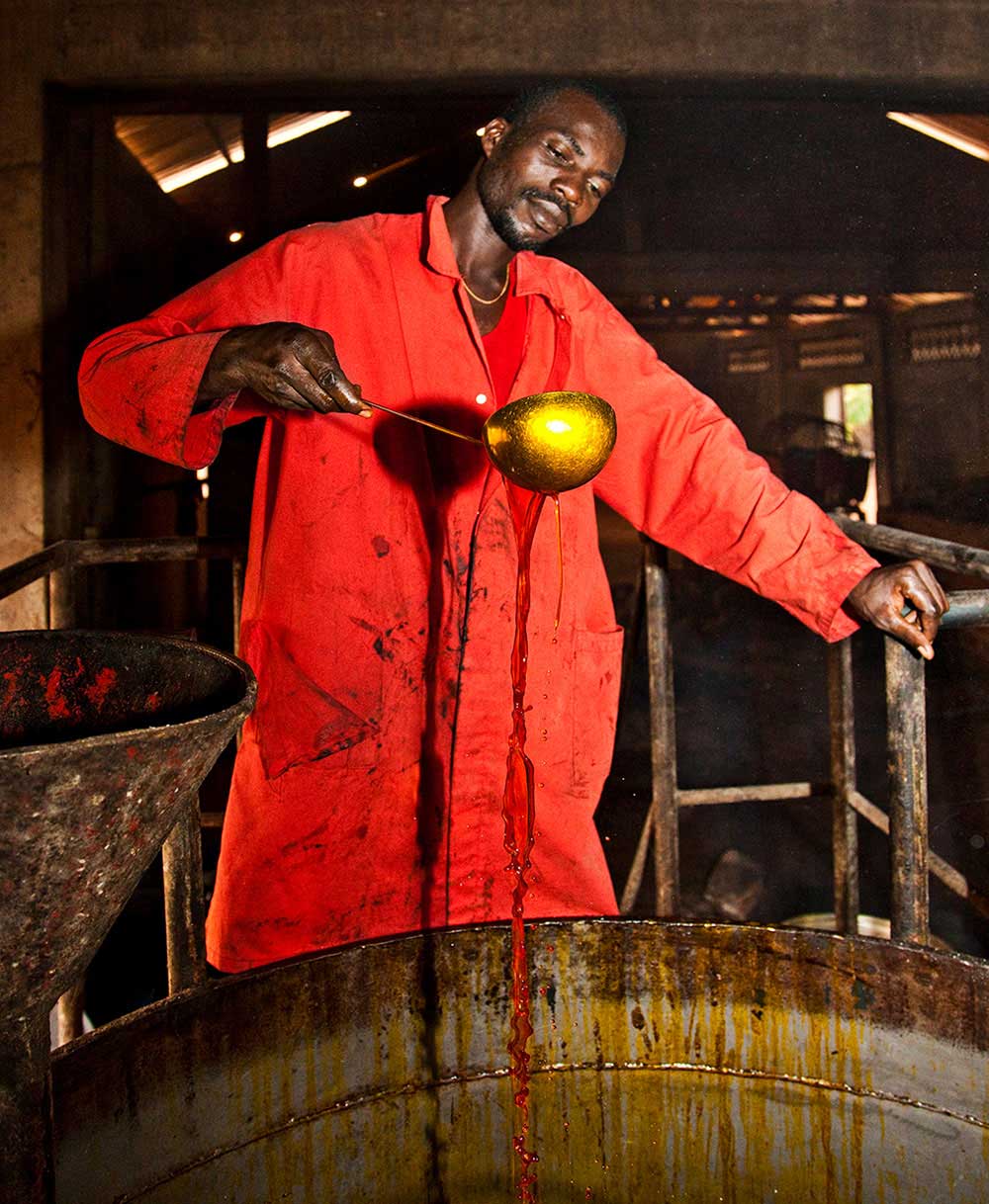

The proceeds are then poured into a second boiler and cooked for hours with a little water. During this process the crude oil cleanse itself of the heavier impurities that remain at the bottom of the container. Water is then added, causing stratification, until the lighter layer of oil is pushed to a tap placed on the side of the boiler. The finished product is thus percolated and collected in a metal drum. The process might be uninteresting, but what makes it spectacular is human participation. The work of the workers gives life and charm to the scene.

They move quickly and safely between the vapors and the flames of the wood fires lit under the boilers, between the deafening noise of the machines and the fumes that envelop the work environment. The temperature is close to fifty degrees and I too, while I take them back, live with them this sweat-drenched effort as if I were immersed in water. What gives body to the scene and paints it in strong colors are their gestures, so quick and aware, in rhythm with the machines, the scarcity of light in certain points that contrasts with other violent lights nearby, the sweat that due to the temperature and the fatigue flows copiously on the half-naked faces and bodies, the loud incitements and the orders of the boss: Silvestre, the most expert in the work.

His love for what he does is seen when at the end of the cycle he wears a red suit, brandishes a ladle, and transforms into a “palm oil sommelier”. It is a beautiful and engaging experience, if you can resist with them, to finally get to feel real satisfaction when you harvest the fruit of the effort. Theirs and mine, united. There is the fascination of Dante’s Inferno in this harsh environment, just as hellish is certain desperate situations in this unfortunate country… but softened and humanized by the Paradise of the Discalced Carmelite fathers who help and give dignity to people here