Gibson’s images, in a strong, contrasting black and white, often incorporate fragments with erotic and mysterious nuances, building a narrative meaning through contextualization and surreal juxtaposition.

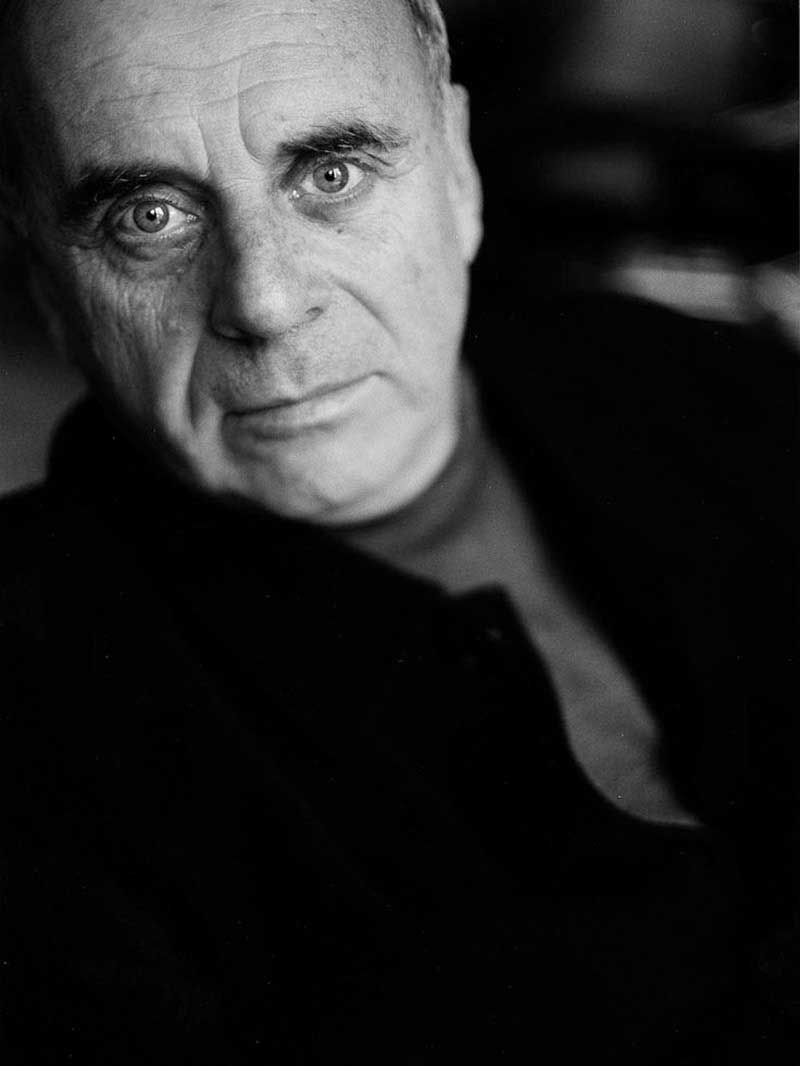

One of the most famous American photographers, he throws you phrases like “Henri told me that” or “Dorothea wanted that”. And he’s talking about Henri Cartier-Bresson and Dorothea Lange, whom he knew very well. And it’s not that he drops names to boast of famous friendships, he is simply a veteran who reflects on the lessons he has learned and the genres he has met during an extraordinary career that shows no signs of giving way.

Ralph Gibson was born on January 16, 1939 in Los Angeles, California. He grew up in Hollywood, with cinema being a part of his daily life. His father worked in the Warner Bros as an assistant director for Alfred Hitchcock. The young Gibson participated as a helper in films and had the opportunity to see the lighting style of the period at work, characterized by strong black and white contrasts, which will definitely mark his future photographic style.

In 1954, his parents got divorced and after lowering his performance at school, he ends up leaving it at age 16. Soon, he began working in mechanics and in 1956, he enrolled as a volunteer in the United States Navy.

A good photograph, like a good painting, speaks with a loud voice and demands time and attention if it is to be fully perceived. An art lover is perfectly willing to hang a painting on a wall for years on end, but ask him to study a single photograph for ten unbroken minutes and he’ll think it’s a waste of time. Staying power is difficult to build into a photograph. Mostly, it takes content. A good photograph can penetrate the subconscious – but only if it is allowed to speak for however much time it needs to get there.

By pure chance, he entered the Naval School of Photography in Florida, thus beginning his training as a photographer. His work in the navy consisted of making portraits, aerial and documentary photography. His enlistment offered him the opportunity to meet different places, such as jazz clubs in New York where he listened to the poems of Allen Ginsberg and other poets.

After finishing his military service in 1960, he enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute and came into contact with Dorothea Lange. He became her assistant for a year and a half, while he developed his own personal style. In 1962, Ralph moved to Los Angeles to work as a graphic reporter, publishing his first works in 1963.

In 1965, his work for the Kennedy Graphics Agency became his first book, ‘The Strip’. His return to his city was short-lived since in 1966 he decided to move his residence to New York. As they say, only with his Leicas and with two hundred dollars in his pocket, he settled in the Chelsea Hotel and very soon he began to interact in the cultural environments of that great city that caught him by his inexhaustible source of inspiration.

To be able to see in concrete terms what was created in a fraction of a second is a rare luxury. Even though fixed in time, a photograph evokes as much feeling as that which comes from music or dance. Whatever the mode – from the snapshot to the decisive moment to multi-media montage – the intent and purpose of photography is to render in visual terms feelings and experiences that often elude the ability of words to describe. In any case, the eyes have it, and the imagination will always soar farther than was expected.

In 1967 he worked as assistant to the well-known photographer Robert Frank, for whom he films, as a cameraman, the films: Me and My Brother and Conversations in Vermont. At that time, he met Larry Clark and Mary Ellen Mark, who influenced his views on photography. He decided to move away from photojournalism and commercial photography. Attracted by the works of writers such as Jorge Luis Borges, poetry and music, he turned to nightlife.

The American photographer’s approach to photography changed radically in 1969, when he moved to New York City, opened a photographic studio and founded the Lustrum Press publishing house in order to keep his own editorial freedom. With his new perception of photography, he adopts a surrealist tone and decides to publish a book, ‘The sonnambulist’, which he published in 1970 and was an immediate success. Because of this book, he was called to give lectures and exhibit his work.

In 1971 he travelled around Europe, taking a large number of photos in England and France, which he later published in his book ‘Déjà vu’ in 1973. During the 1980s, Gibson continued his unique approach in Syntax (1983), L’Anonyme (1986) and Tropism (1987), the latter two books published by Aperture. To date, Ralph Gibson has produced over 40 monographs.

His photographs are included in over one hundred and fifty museum collections worldwide and have appeared in hundreds of exhibitions. Gibson received scholarships from the National Endowment for the Arts (1973, 1975, 1986), a Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst scholarship (DAAD 1977), a scholarship from the Council of the Arts (CAPS) of New York (1977), and of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (1985).

Gibson has received an honorary doctorate of fine arts from the University of Maryland (1991) and a second honorary doctorate from Ohio Wesleyan University (1998), among many other awards.

To communicate requires that those who view the work also understand. Fortunately, people respond to visual stimulus on more than one level. Abstraction, for instance, has always played a big role in artistic expression, and it is becoming more accepted in photographs. There’s nothing new about abstraction in painting, but for some reason people respect painting more than photography. This might be because photographs are so widely used by the media in this culture that they are regarded as mere ephemera… you look at a photograph once and then turn the page