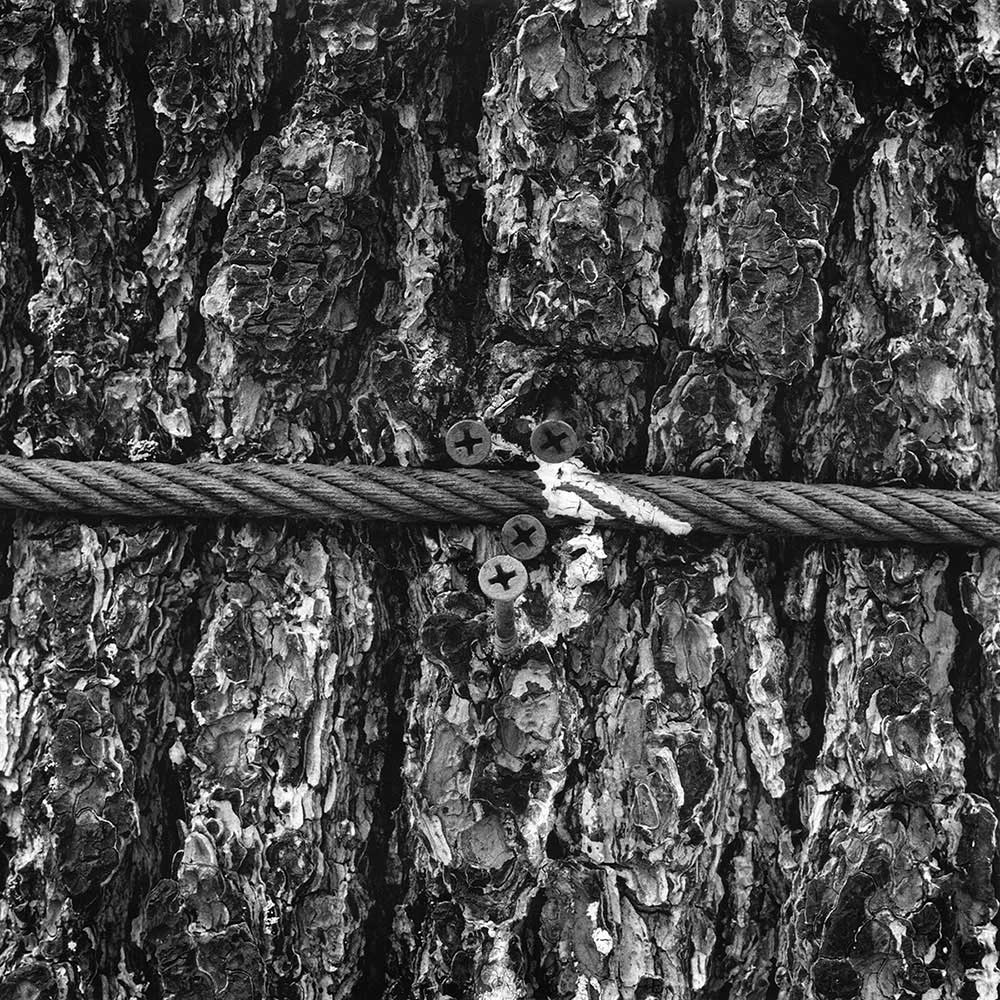

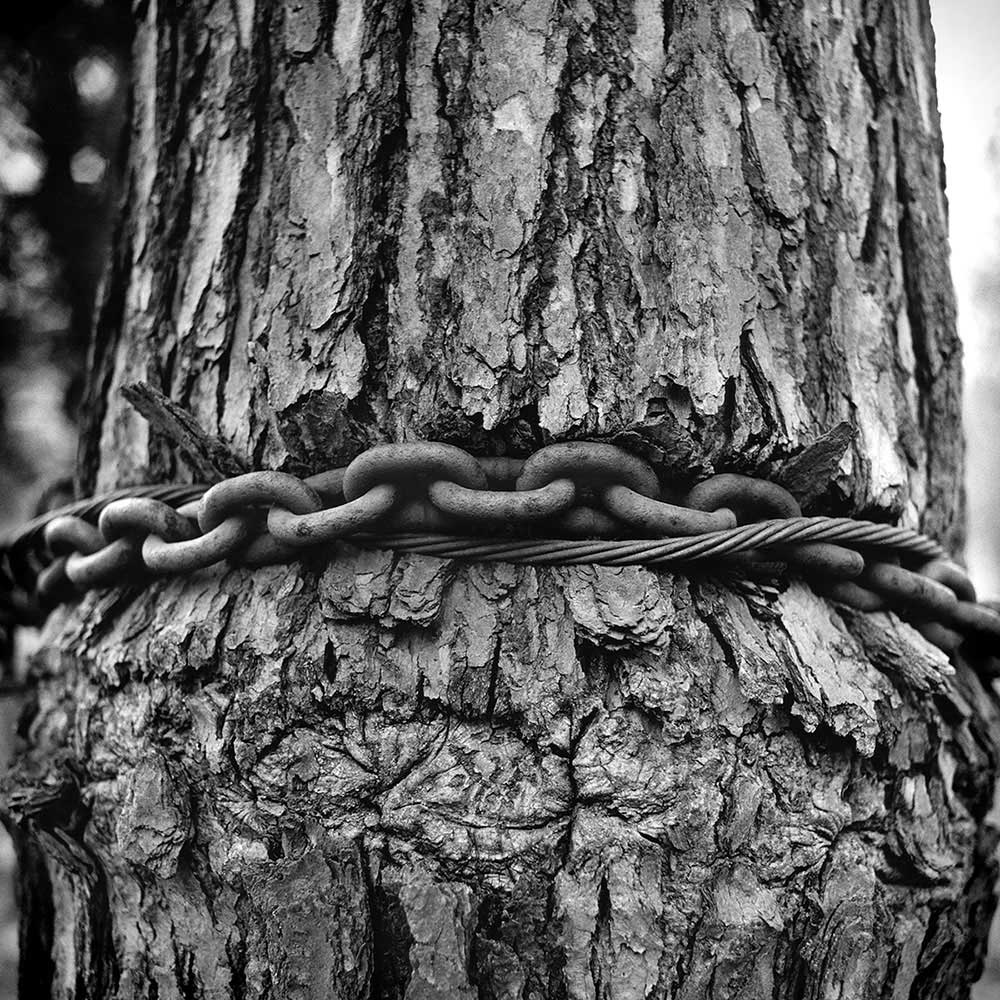

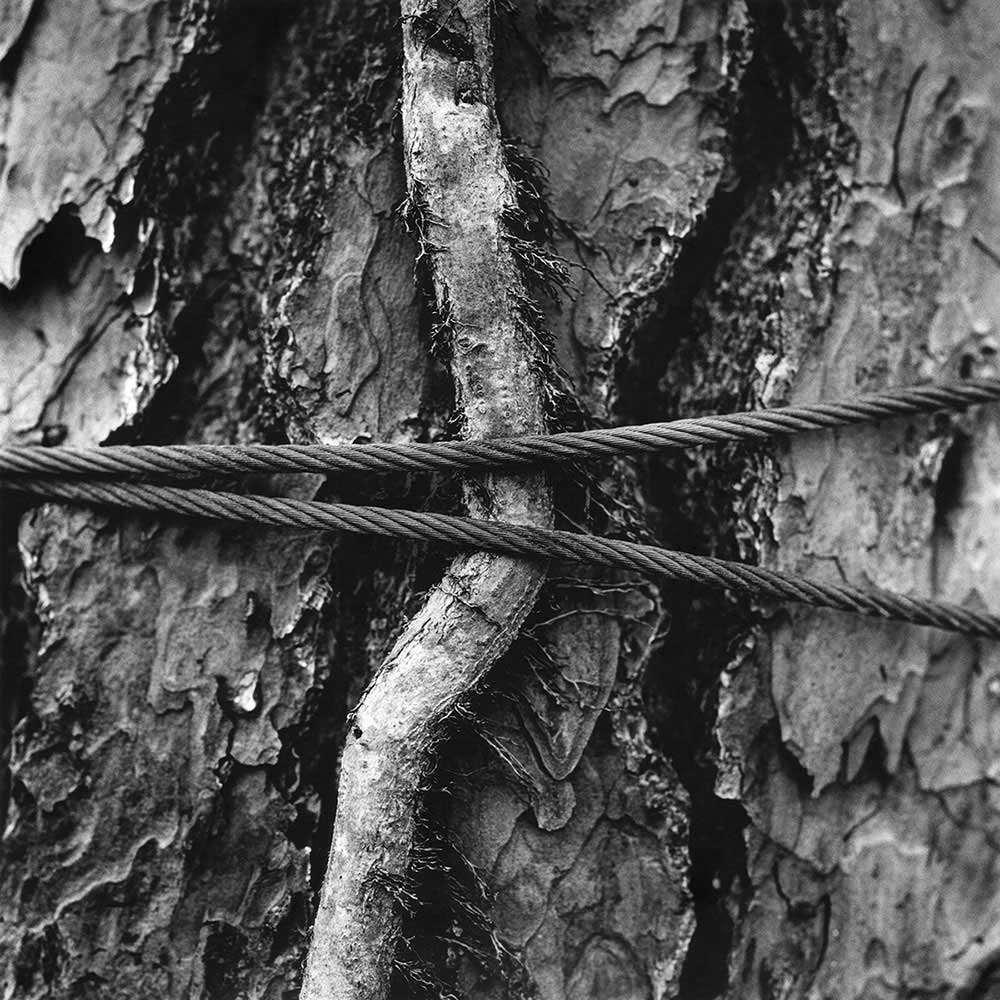

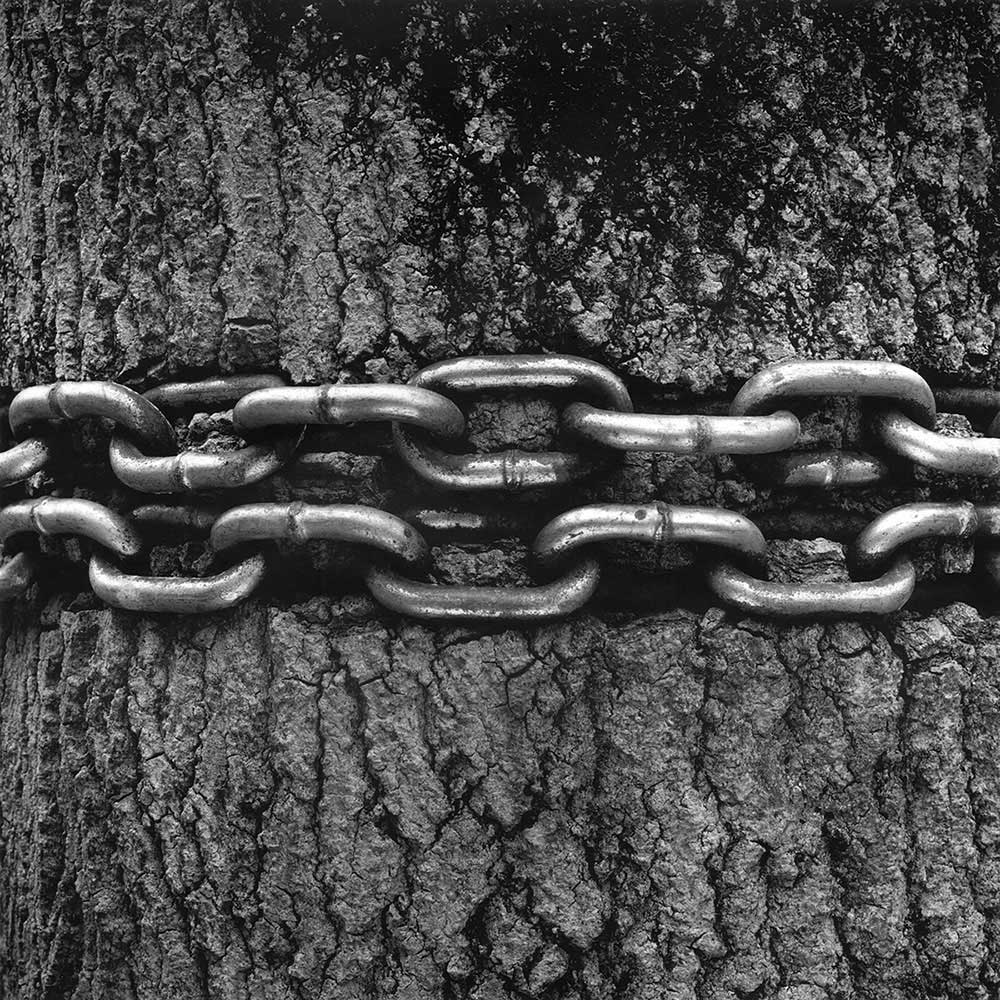

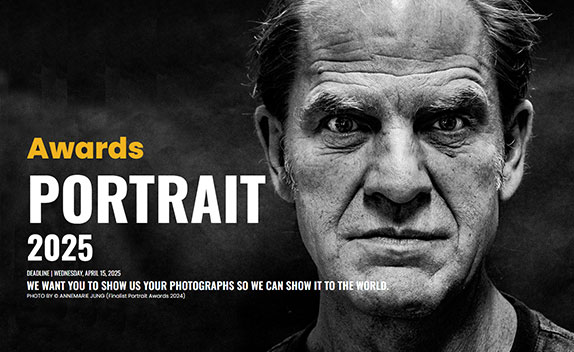

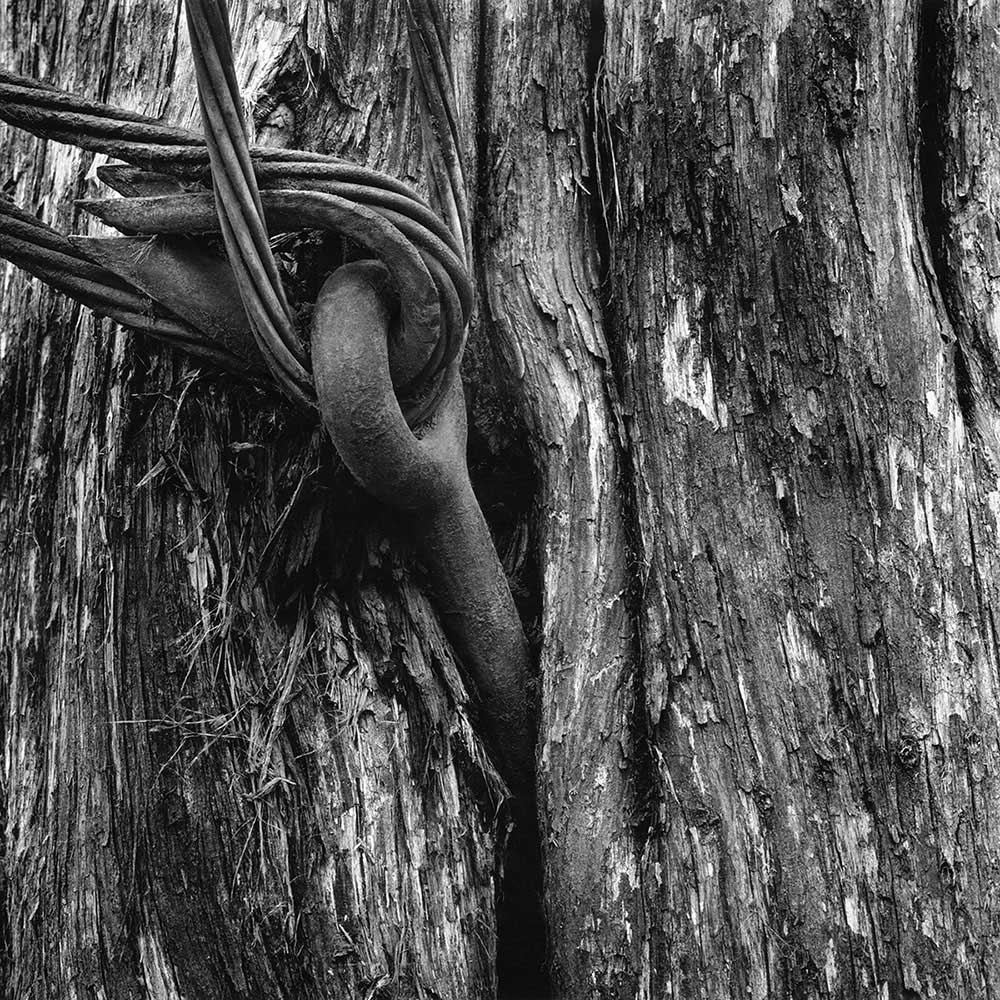

Used to restrict access to the landowner’s property, this series of photographs focuses on trees that have been used as supports for a variety of chains, cables, or sections of fencing.

Over time, as these trees continue to grow with these constricting bands of material, the dialectical tension between man and nature builds to a particular emotional pitch. As the wires, cables, and chains cut into the trunks of the trees (a process literally called ‘strangulation’), the organic vegetal response seems to embody human, visceral feelings of pain, emotional constriction, and dogged survival.

Titled, Rapt, this series of photographs open in a landscape of tightly focused moments of intricately beautiful yet anguishing and intense engagements between man and nature. The sites I photographed spoke to me strongest in the days of transition from winter to spring when the scenes were enveloped in flat, grey light and when there was no foliage on the trees, leaving them naked and exposing the oppressive man-made indignities.

All of the images were shot using black and white analog film in a medium square format camera. Given the focus of the subject matter on the physical and material organic workings of plant life and the oxidation of metal, it was critical to the logic of the series to maintain the immediacy of their chemical, indexical imprint on film, and its translation onto a slightly warm tone, semi-matte, fibre-based photo paper, creating a substantial presence that would have been impossible to achieve digitally.

Narrative

Two years ago, I began writing about Rapt. I did a deep dive search of online dictionaries and thesauruses looking for descriptive words that represented the underpinnings of the photographs and I compiled one full page of short terms and single words. Just as I was about to start drafting a rough outline for the essay, I received a Juror Summons in the mail from the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta. I knew that the Court tries the most serious criminal offenses in Canada including murder. Since our midsize prairie town doesn’t often hold trials for such grave cases, the timing seemed uncanny. I tried to set the writing process aside but I couldn’t keep it out of my mind. At the end of the random jury selection process, I was chosen to be one of twelve jurists in what was described as a second-degree murder case. The more I learned of the disturbing and gruesome details, the more distressing and yet captivating it became. My curiosity had been triggered.

Murder is the ultimate act of violence and oppression. There are many reasons that might provoke someone to kill but the darkness to do so is beyond most of our imaginations. For some, the unconscious mind can become an overwhelmed, tangled, thorny web of toxic unresolved feelings from the past. They are interwoven into the innermost depths of the complicated human mind. We all have our own unique and challenging life experiences. Here are some of mine.

After graduating from art school in 1980, I whole-heartedly pursued a career in fashion photography. After quickly exhausting the few opportunities in Alberta, I followed my passions and departed for Milan, Italy, one of the pinnacles in the fashion world. The first few years were discouraging and bleak (I ate a lot of pasta). However, with unyielding persistence and a desire not to suffer the embarrassment and pressure of failing, things slowly began to appear more upbeat. My photographs started appearing in fashion publications in Italy and the UK. Eight years later I relocated to New York.

Within a short period of time, my crew and I were traveling the world on assignments to fulfill my client’s needs. My obsessive attention to detail, choices in design, style, and aesthetics became desired by creative directors and fashion editors, allowing me to shoot colorful, glossy editorial spreads for prestigious fashion magazines and some of the superpowers in the retail fashion business. Life was beautiful.

However, as we all know too well, what goes up must come down. The Great Recession and meltdown of the U.S. economy in 2008 was followed by my own meltdown and personal life crisis. In reality, my life had started spinning out of control long before this, but that awareness was unfortunately being unconsciously repressed.

Like in many economic downturns, advertising, and editorial budgets evaporated overnight and many commercial creative careers were left in shambles. For too long I looked backward and not forward to what could be the next step in my photographic journey. In retrospect, freelance fashion photography generously paid the bills, provided for a very exciting lifestyle, and a very busy social life, but it ultimately left me feeling gutted as an artist. At the same time, my unhealthy personal relationships outside of my professional life started to become strained.

I sought professional help that resulted in a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy but I didn’t stick with them and went ‘cold turkey’. I chose not to address the new reality (the truth) but rather lived in a toxic mixture of addictive, intoxicating, and obsessive catastrophic thoughts of grief and loss. I had moved from repression to suppression. I was a mess.

Living in the endless gloom of overpowering darkness and paralyzing denial ultimately led to my short stay at the Mount Sinai Psychiatric Ward in Upper Manhattan. Both my emotional health and mental health required urgent attention. Eventually, I’d learn that mental health is how well the mind processes and understands information and experiences. In contrast, emotional health involves the ability to manage and express the emotions that arise from what you have learned and experienced. Soon I was back on the sofa of my therapist John. Week after week, month after month for two years, I would say the same things over and over again, until it finally started to make sense.

It took a while and eventually, I decided to enroll in a History of Photography class at a nearby university in New York. After that, I completed two additional courses and also audited a History of Surrealism class that helped me understand how the evoking of feelings through the use of visual art can happen in the unconscious mind. My passion for fine art photography had been re-energized.

Reflecting on the recent curator’s talk for Perspectives From Within, a group exhibition some of the images from Rapt were shown in, he referred to the five steps of flourishing: playing, interacting, connecting, learning, and helping. Examining the list of the five essentials, it is obvious to me now that some of these key elements to flourish were absent in my life or at least not in sync with each other and perhaps they rarely are. My decision to go back to school and ‘learn’ allowed me in part to flourish again. A major crisis had been averted although my journey with depression continues to this day.

That brings us to my current art practice. Nine years ago and six interrelated series later, my persistent curiosity and commitment to producing new project related series of photographs continues, and through it, I’m happy to expose my own Perspectives from Within and I’m open to “Putting It All On The Line” (a recent essay on my work by Beth E. Wilson).

The scenes that I am most attracted to are simple and ordinary. Based on isolating and elevating the unseen, they require deeper looking by attuning our perceptions with our emotions. The objects are simple, ubiquitous, and are everywhere around us. The photographs contain the requirements that fulfill the medium’s technical visual language such as form, sharp focus, rich detail, contrast, and rich tonalities also collectively known as ‘straight photography’. The photographs, at first sight, are physical, material representations of reality. Additionally, they are analog-based (or film-based), an intentional choice over digital technology, making them materialistic in nature. They are, however, much more than this.

A photograph can provide an “optical unconscious” as described by Walter Benjamin, a German philosopher, and critical thinker. Benjamin tells us that the optical unconscious, unique to still photography, allows us to see things in a photograph that we would normally not be sensitive to, the invisible and the unseen. It permits us to unveil or access a part of the mind containing feelings, desires, images and ideas not always visible for direct analysis or scrutiny. Attuned to the ambiguous and abstract nature of life, this series of photographs is multi-layered with metaphors exposing my own issues of fear, loss, pain, impermanence, abandonment, and mortality.

Figuratively, the images raise the human issue of control and subjugation. The open wounds and scars suggestively speak to present-day concerns of social injustice such as domestic and sexual abuse, racial, gender, and wealth inequalities, and the attacks on our freedom such as the abuse of power and the assault on voting rights. Additionally, they address the question of the value and use of resources and proprietary entitlements.

Not wavering from my obsessive personality, strict parameters were once again established for this series. All the photographs were to be shot in the days of transition from winter to spring, when the scenes were enveloped in flat, grey light and when there was no foliage on the trees to minimize distraction as if the trees wore no clothes. Additionally, there could be no moisture of any kind, rain, snow, or even droplets of dew. All of the sites that were to be photographed were to be located within the boundaries of Ulster County, N.Y. although there are two newly added exceptions.

From frame to frame they consistently were to be shot at a straight-on, frontal, and level camera angle to avoid any distortion. This would allow the viewer to identify with the object from a close-up and subjective point of view. They had to remain simple, natural, and matter-of-fact. These parameters were intentional in every way as they were selected to heighten the symbolic significance of the elements. For example, the flat, grey light was similar to the brain fog I was experiencing in my depression. It also represented a greyscale equivalent to the effects of the anti-depressants I had experienced. There were few highs and few lows. In all truth, often there was just a lot of grey. Suitably, all of my series are photographed in black and white.

Before setting out to photograph this series of trees with the constricting cables and chains wrapped around them, I had pre-envisioned the printed images to be presented in a grid format rather than side-by-side in a single line. The tightly spaced, stacked grouping would be symbolic of the intense anxiety relentlessly preoccupying my mind.

The grid would also reinforce the objective point of view – the physical and material representation of objects that possess a common relationship. The format compliments the idea of typology by strongly reinforcing classifications based on types or categories. Over time, my mind created a catalog of these objects. Grouping them in a grid format presents them in a physical catalog while simultaneously reinforcing the cataloging occurring in the mind.

Finally in titling this series, I sought a single word that would be inclusive of the gut-wrenching physical and mental anguish I experienced when developing the photographs in my darkroom as if a constricting chain was wrapped around my neck or a piece of piercing barbed-wire was surgically burying itself into my flesh. I wanted a word that would address the twisted, dark, euphoric pleasure present in my addiction to my self-inflicted mental torture during my darkest days of depression. Finally, the word had to capture the strange bifurcated world of beauty and brutality that exists in the photographs of these oppressive man-made indignities. Rapt.

Moving from working in total darkness to the red amber ambiance of the darkroom’s safelight brought therapeutic comfort and warmth, some solace. The choice of nostalgic music from the late 1960s and 1970s enhanced the chemically saturated air. Perhaps it was a yearning to return to my adolescence and the beauty of youth when things appeared less complicated.

In a very peculiar way, the long sequence of events presented in the murder trial and the conflicting arguments of the prosecution and defense, bared an odd similarity to the time I spent on my therapist’s couch. As disturbing as it was, over and over again, in the courtroom and in our jury room deliberations, I listened and watched the brutal and horrifying doorbell audio and video recordings of the accused offender repeatedly stabbing the victim with a knife thirteen times, until it all made sense to me. We viewed it assiduously, forward and backward, fast forward, quick rewind, normal speed, slower speed, frame by frame and freeze frame. After two long days of examining and deliberating the hard evidence of the case, the jury in sequestration, reached a unanimous and fully conscious decision. We returned to the courtroom.

Sitting in the jury box, I rose from the uncomfortable chair to my feet. My knees wobbled as I awkwardly glanced at the accused offender seated directly across from me. I looked away, took a very deep breath, and announced the verdict. I could hear someone weep.

About Wes Bell

Wes Bell was born and raised in Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada. From an early age he was fascinated by art, which led him to the studio-intensive program at the Alberta University of the Arts, where he received his Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography.

After school he pursued a career in fashion photography. Bell lived and worked in Milan and London, eventually relocating to New York, while travelling extensively on assignments to the far corners of the world. His acute sense of design, style and aesthetics are highly respected by art directors and fashion editors, leading to editorial spreads in publications such as British GQ and Esquire, Conde Nast Traveler, The New York Times Magazine and People.

After residing in New York for more than twenty years, Wes returned to live in Alberta six years ago. Since departing the fast-paced world of freelance fashion photography, he has reignited his passion for fine art photography, and today photographs on location, responding to the detail and natural beauty in the environments that surround him.

Bell’s black and white photographs have been exhibited internationally in both solo exhibitions and in numerous group shows, including the upcoming Oil – Beauty and Horror in the Petro Age at the Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg, Germany, in 2021. He is the recipient of the LensCulture Exposure Awards 2017 – Jurist Award as selected by MaryAnne Golon, Director of Photography at The Washington Post. He also received the 2017 Bronze Award for the Royal Photographic Society International Photography Exhibition 160 in the United Kingdom. He is currently working on a book project called On the Line, which includes six inter-related series: Lost for Words, Final Steps, Rapt, Snag, In Plain Site and Callus. [Official Website]