Those people are Russians, but they are not Russians. There’s four million of them in Russia, but they are seldom talked about. They speak different languages, but they are united by simple everyday wisdom and the kinship with earth. As if they stem from the earth – like stones and trees.

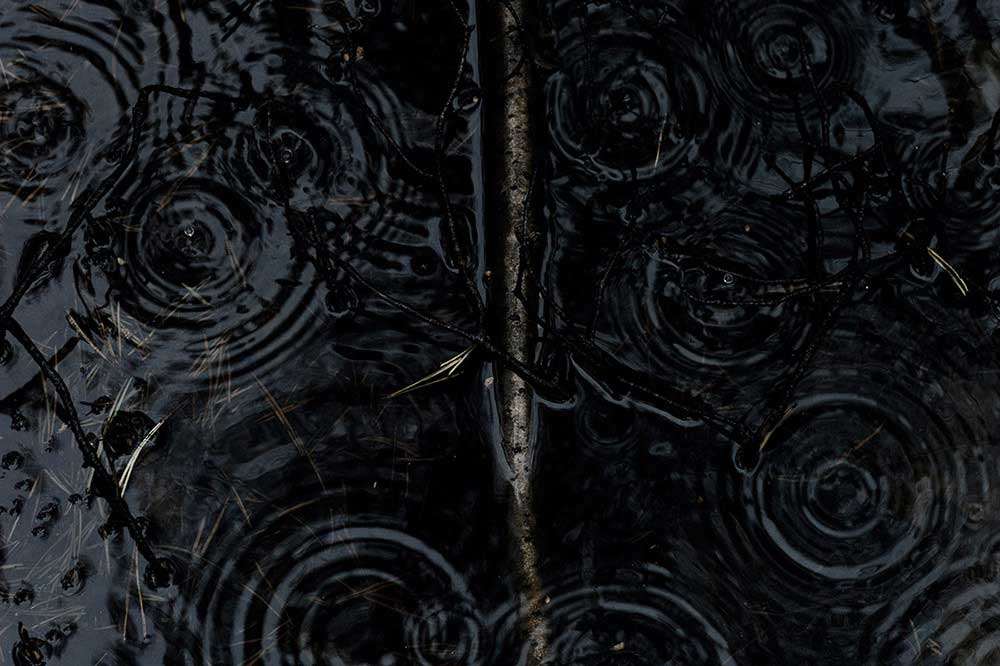

They are pagans – or, having converted to Christianity or Islam, they are still pagans without fully realising it. Their world is different, full of archaic things, full of cruel straightforwardness of childhood. The great Russian poet Blok wrote: The Finns have made follies, the Meria have measured. Here lived pantheists and warlocks, their main religion always having been Nature.

This is Finno-Ugric land. The people of that civilisation have been and remain the first dwellers of this land. From them came many of our customs, our tales, our roots – mine included, as it turned out. If you only go a couple of hundred miles to the East of Moscow or St.-Petersburg, you will see the Finno-Ugric matrix through the familiar reality of the depressing provincial routine. It stretches all the way to the Ural mountains and beyond. The traces of tradition are alive in many villages along the Volga. And farther away, beyond the Kama river, where the Orthodox Church was never strong, tens of thousands of real pagans live. This phenomenon in the supposedly totally Orthodox Russia is a silent agreement of the people with their rulers.

Not any guest will get the depth right away. The rituals aren’t bright here. In contrast with, say, the Siberians, the Udmurts or the Mari don’t have the blindingly beautiful costumes, the striking throat singing. The local pagan rite isn’t about visual effects, it is very calm.

People are quiet about it also because there is a dark side to it. Here’s a story from an Udmurt village: the village chief took apart the prayer house – kuala – and rafted the logs down the river. A few days later, a fanatic cut off his head. And those stories are plenty. Perhaps some of them are made up, but there’s a grain of truth in any legend. And thus these people live in a “parallel reality”. How much longer can it last in the age of rapid globalisation? So far, it is still possible to hear their wisdom, look at nature, at the world and at oneself through their eyes. And that will stay with me.

About Dmitry Ermakov

Dmitry Ermakov, born 1978 in Moscow, Russia. Educated as an aviation engineer in MATI, Moscow. Took first steps as a professional photojournalist in 2006. Worked as a writing journalist in 2004-2013, then completely moved into visual media. Studied photography from Maria Ionova-Gribina, Artem Zhitenev (Moscow), Sergey Sarakhanov (Kiev / St. Petersburg). Graduated from Fotografika academy in 2018.

In 2013-16 worked as staff photographer/cameraman for Anadolu Agency, Moscow Agency. Works as a freelancer for BBC Russia, Russia Beyond, Roads & Kingdoms, Greenpeace, Moscow Government and others. In his stories, Ermakov works with cultural codes of Russian people and communities, exploring the themes of ancient and modern myths. He works with social and political issues as well. Dmitry combines documental stories with an art form, paying great attention to color. He’s inspired by modern Scandinavian art and documentary photo. Dmitry is the winner of Eastreet 4 contest on genre photo (2017). Shortlisted in Down By The River genre photo contest (2017). Participated in Actual Udmurtia contemporary art exhibition (2015-16), FUFF-2016 film festival, Borders experimental photography exhibition (2018), Memory Card photography exhibition (2018). [Official Website]