Bob Newman is a retired physician, who for the past 15 years, has been working as a professional photographer engaged in long-term projects.

His career in medicine, with a practice that served disadvantaged communities, guides his work as a visual storyteller. He is drawn to collaborating with members of marginalized communities to document the challenges they face and the richness of their cultures.

He was recently chosen as a Finalist for the 2022 Critical Mass competition. International Photography Awards (IPA) selected him as Deeper Perspective 2021 Photographer of the Year and as a Jury Top Five Selection. He received LensCulture’s Critic’s Choice Award and was named a 2021 Finalist for Photolucida Critical Mass and The London International Creative Competition. Independent Photographer included his images as part of the “2021 Through 10 Compelling Photographs” Retrospective.

In 2020, he was named to the Critical Mass Top 50, Short Listed in the Portrait of Humanity Competition, named a Finalist in the Fresh Annual Summer Exhibition, and selected as Portrait Finalist at the Head On Photo Festival (Sydney, Australia). International Photography Awards (IPA) selected thirteen pf his images for awards including Jury Top 5, First Place and Honorable Mentions.

He participated in VII Photo’s 2018-2019 Masterclass in Warsaw and the 2019 Eddie Adams Workshop. Additional awards received in 2019 recognizing the quality of his images include Travel Photography of the Year Finalist and International Photography Awards Best of Show & 1st Place Awards.

I was raised in a small town in northwest Oklahoma in the 1950s. Though I did not realize it until I was an adult, it was a Sundown town. Black people were not allowed to stay overnight within the city limits. Lots of towns in the South were like that at the time. While I am not aware of any Blacks being mistreated or injured in my hometown, though that did sometimes happen in other locations.

Growing up, I had no concept of what it was like to live in the Mississippi Delta, where Emmett Till went to visit his family in August of 1955. I was five years old when Emmett was murdered and I was insulated from interactions with Black people until later in life.

In the 1950’s, Jim Crow laws were still in effect in the Delta. Those laws affected every aspect of life for Black Americans in the South. Direct eye contact was forbidden and Black citizens had to walk in the street rather than share the sidewalk with white citizens. Under no circumstances could a Black person assume an air of equality with a white person.

Fast forward to 2014, when I made my first trip to the Delta and stepped into the Tallahatchie County courtroom in Sumner, Mississippi, where the 1955 trial of Emmett’s killers took place. (They were found “not guilty” but later confessed to kidnapping and murder.) I was inspired to learn more about what happened to Emmett and how it impacted the Mississippi Delta of today.

As a white man, I have wanted to see things as viewed from the Black perspective. Consequently, it has been a daunting task to tell the story of the Delta in a thoughtful way while depicting the dignity of those who have live and have lived there, both Black and white.

I cannot know what it is like to be Black. But I do know what it felt like to stand on the Black Bayou Bridge where he was thrown into the Tallahatchie River with a 75-pound cotton gin fan tied around his neck and to see the bullet ridden sign marking the site on the river where his body was found. I am horrified to think how terrified Emmett must have been on that dark August night in 1955. That threatening undercurrent of darkness and menace remains and will not let go.

The Mississippi Delta has been called “The Most Southern Place on Earth,” a region of layered histories that collide with each other on a daily basis. It’s a place that defines America and Americans like no other part of the country – a culture entwined with slavery, poverty, and political and economic oppression. It is the land that gave birth to the creative genius of Muddy Waters and B.B. King, and to the horror of the Civil Rights-era murder of young Emmett Till.

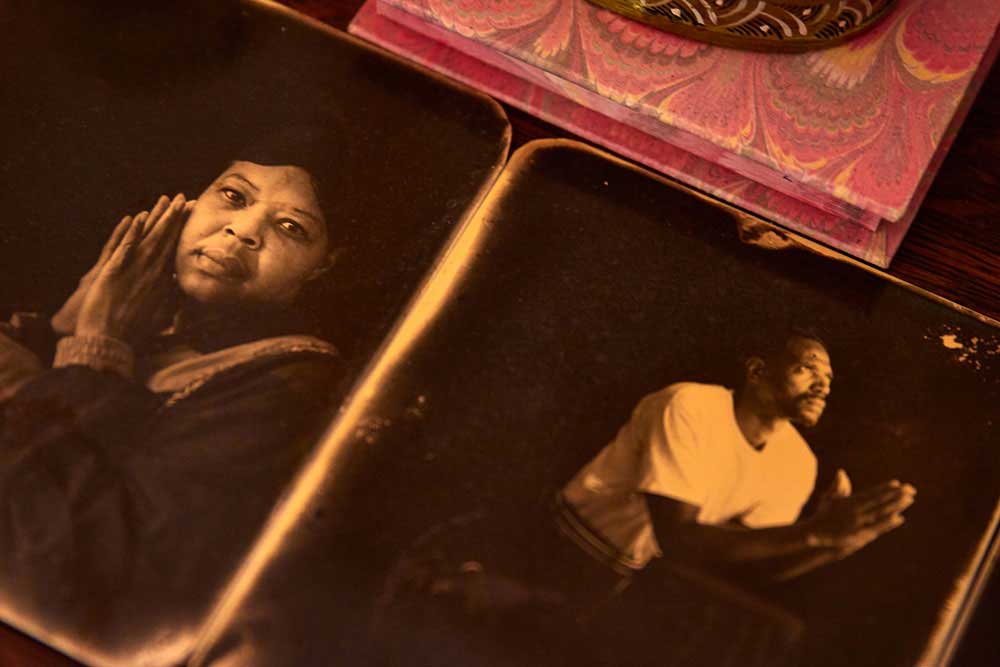

These images and my Shadows of Emmett Till book seek to probe that complex past: picturing the energy of a landscape that has bred both hatred and creativity, interrogating the whiteness that has always held power in its grip in a place that is predominantly Black, and observing the many ways the shadow of Till’s murder still hangs over the Delta. This is work that breathes the Delta air and seeks to frame the region and its people in a 21st-century context, at a time when white America may be starting to finally come to terms with the sins of its past.

The Mississippi Delta stretches from Memphis to Vicksburg. Hard times, hot humid weather, flooding, and destitution are facts of life. Since 2014, I’ve photographed in over 40 towns and roamed countless miles across the land.

Though segregation is no longer present, there are Black and white barbershops, churches, and cemeteries, even in small towns. Black and white people to interact but separation is still evident. In some ways, Mississippi is frozen in time.

While photographing, more than once, I’ve stood on the Black Bayou Bridge where Emmett’s body was thrown into the river and have worked to make a photo that honors him and his legacy. Again and again, I see the past spilling into the present. As I photograph the remnants of Emmett’s time, I am finding troubling parallels with George Floyd and so many others.

By and large, the people in the Delta have been friendly and open to being photographed. This series of images provides a glimpse of what life is like in the Mississippi Delta of today and what remains of Emmett Till’s time.

For those who might want to take a deeper look, my book, Shadows of Emmett Till, was published this fall by Kehrer Verlag – Heidelberg; it is available on my website, through Kehrer Verlag, and in good bookstores.