There is a kind of paradox in Steve McCurry’s photography. On a technical level, his photos are practically perfect, serene, characterized by the strength and liveliness of the color, but they tell of disturbing stories of poverty and eradication, hunger and despair.

It may seem like a lack of empathy with the photographed subjects, but in reality, it is the opposite. His images are the result of painstaking research, made through long journeys and exhausting expectations of the perfect moment.

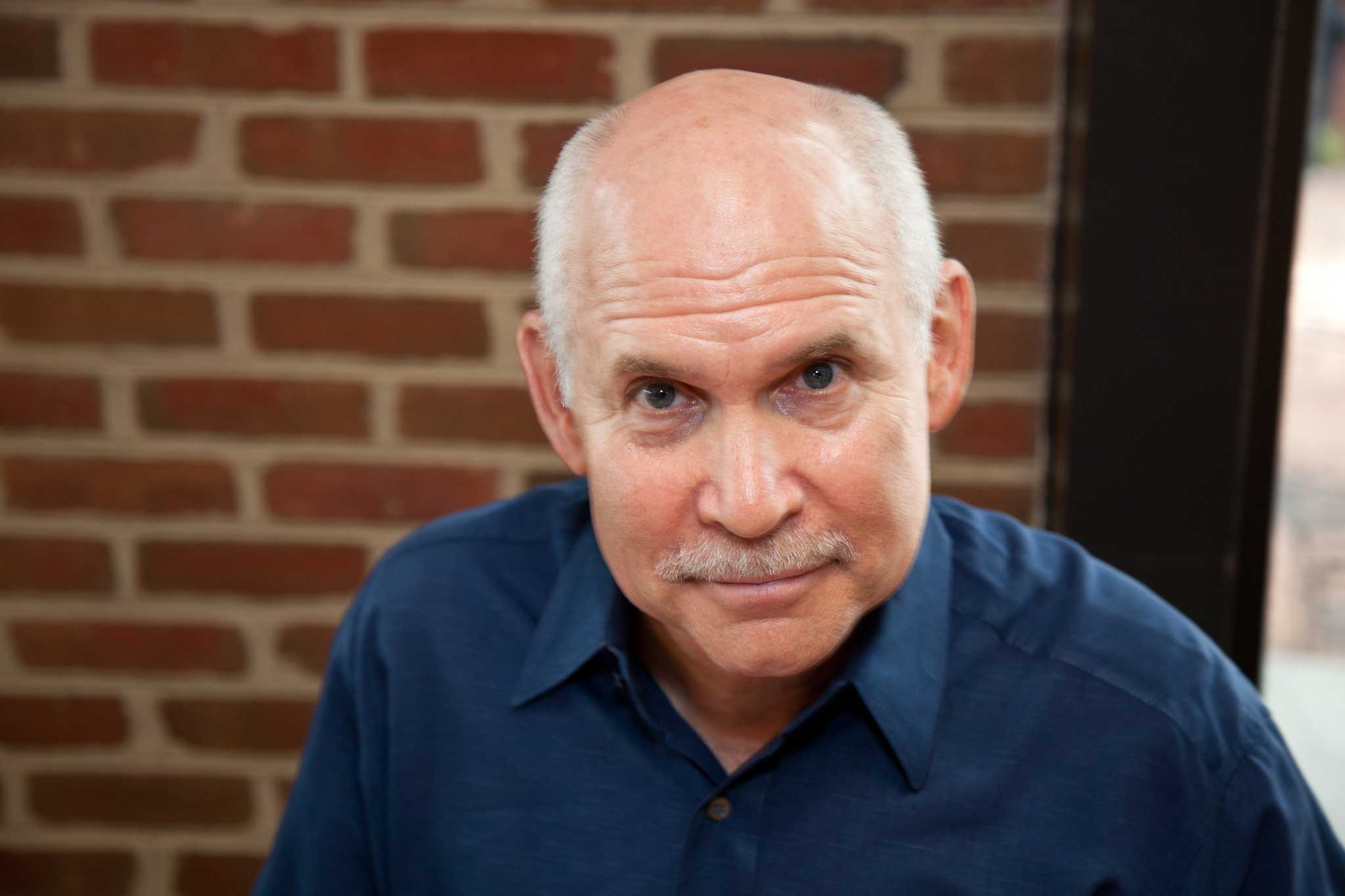

Steve McCurry was born in Philadelphia, United States on February 24, 1950. From an early age he showed an interest in photography, so he began his studies in the history of cinematography at the Pennsylvania State University of Arts and Architecture, with a great effort and showing a great passion for what he did.

However he took another course, choosing the performing arts, a career from which he graduated as cum laude in 1974. He started working at a newspaper called “The daily collegian”, where he discovered that photography was his passion and started learning different techniques that would help him in the future.

He also worked for “Today’s Post” and then decided to go to India to work as a freelance. There, he started to train his style, in addition to developing an impressive look when assembling the compositions of his photos, contextualizing the photographic object with the environment. It was also where he learned his innate skill: waiting for the perfect shot.

My life is shaped by the urgent need to wander and observe, and my camera is my passport.

Few photographers would go to the extreme that McCurry went in order to obtain those coveted images. His first foray into photojournalism was his coverage of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. In 1979, he went to Afghanistan to cover the conflict in the region. But it was in 1980 when he reached a point that would be decisive in his career: he crossed the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan (controlled by rebels) dressing like a native, just before the Russian invasion.

He hid his film by stitching it onto his clothes and was able to smuggle these shots in, providing some of the first ever-seen photos of the conflict. Those photos kicked off his career boom to become a world-class photographer.

Such an act made it possible for him to show, through photographs, striking images of a war-torn zone, making the world understand the cruel reality of the conflict in that region. This achievement won him the “Robert Capa” award as the best photo report, given only to the best photographers who show their exceptional courage and dedication in the profession.

He continued to cover other war events for years, such as the war between Iraq and Iran, the Gulf War and Cambodia. His photographs reflect the great damage and suffering that wars cause to people, capturing their emotions at the right moment.

He does not describe himself as a war photographer, but focuses on the human reality of war, demonstrating how much a landscape or a face can impress. McCurry has had death brushing his heels. Arrested and shackled in Pakistan, nearly drowned in Slovenia and India, downed in India also by enthusiastic crowds, and survived an assassination attempt by a Muhajideen.

What is important to my work is the individual picture. I photograph stories on assignment, and of course they have to be put together coherently. But what matters most is that each picture stands on its own, with its own place and feeling

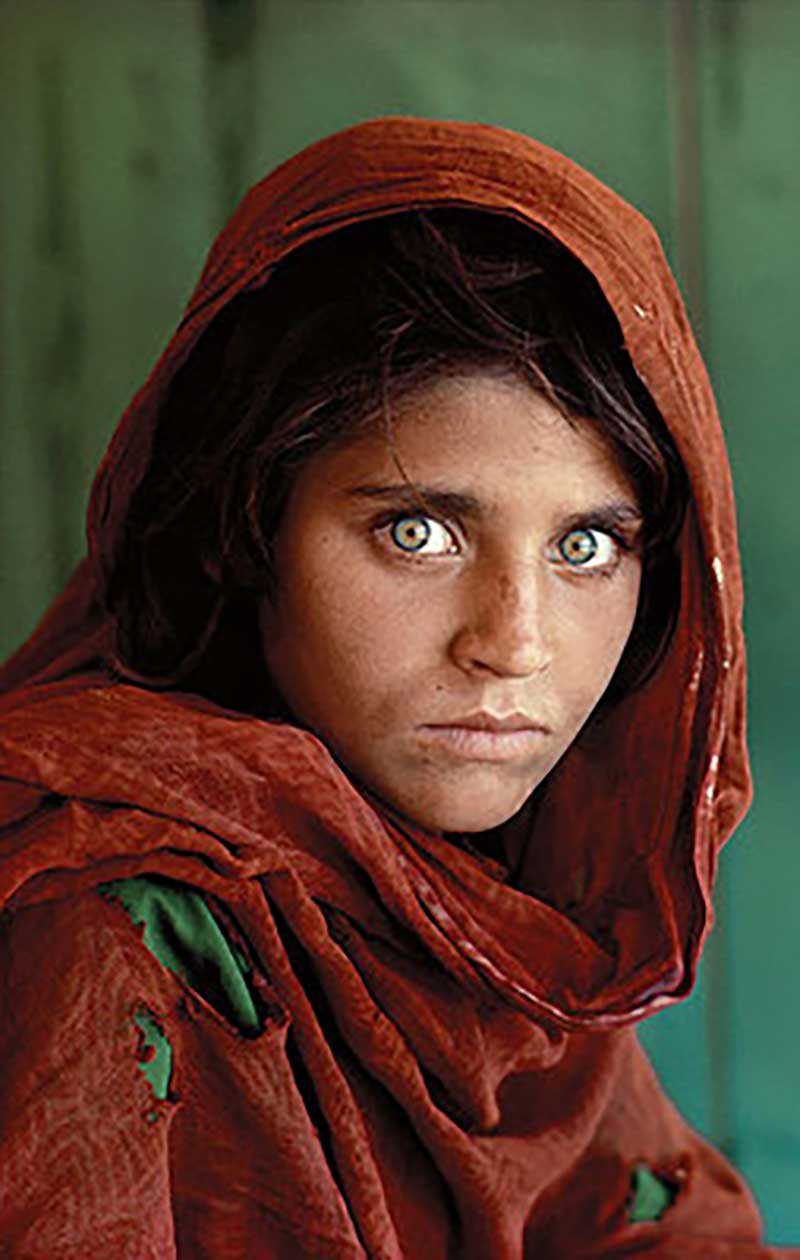

There is a photograph that most people undoubtedly recognize. It was 1984, Steve was photographing in an Afghan refugee camp in Pakistan; until a 12-year-old girl called his attention: it was Sharbat Gula, an Afghan woman who had lost her parents in a Soviet bombing in Afghanistan.

The photograph named “Afghan girl” appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine, in the June 1985 issue. The image of her face with a fabric wrapped around her head and her green eyes looking directly into the camera, became a symbol the conflict between Afghans and the situation of refugees around the world. Gula’s photo, which calls attention for the composition of colors, was named as the most recognized photograph in the magazine’s history.

Close to New York’s Twin Towers during 9/11, he rushed to Ground Zero, capturing poignant images of injustice, pain, and support from New Yorkers at this sadly historic moment.

He has toured the most inhospitable places in the world, capturing with incredible reality and naturalness the people and lands he visited. Thousands of photographs speak of the years of dedication to his work.

He is a major contributor to National Geographic and has been with the Magnum agency since 1986.

A still photograph is something which you can always go back to. You can put it on your wall and look at it again and again. Because it is that frozen moment. I think it tends to burn into your psyche. It becomes ingrained in your mind. A powerful picture becomes iconic of a place or a time or a situation.