The Dominoes of Deceit places along the frame a vertical and horizontal array of men who are seemingly conflicted and yet non-confrontational.

The primarily dominant subject on the front right end of the frame masks an expression of seeing and yet (not) knowing the possibly vengeful intention of his scissored impostor. Suspense further brews into the frame with two optical illusions. One, of the simultaneous act of the older barber performing a shave that is reflected in the back mirror. However, if kept out of sight, the mirror leaves obscure the possibility of the older barber reaching out for the scissored juvenile. The stifling cluster of multiple angles and directions of deceit are given an overarching possibility of the voyeur’s frame being a mirror through which they themselves might be looking in hindsight, hence calling for a crucial reflection into their own demons. The side drop has a man interrupting the frame while peering into his cellphone to possibly scan the temporal tension of the situation or evade its very occurrence altogether. A bearded man at the centre seems to be peering one-sidedly into what the figures behind him hint to be a spectacle. The contrasting stacks behind them loom over their own compulsiveness to intrude and yet rarely confront. Lastly, the unidirectional arrangement of this centrifugal composition encourages a pressing inquiry into our juxtaposed interplay between vendetta and redemption.

About Urvashi Singh

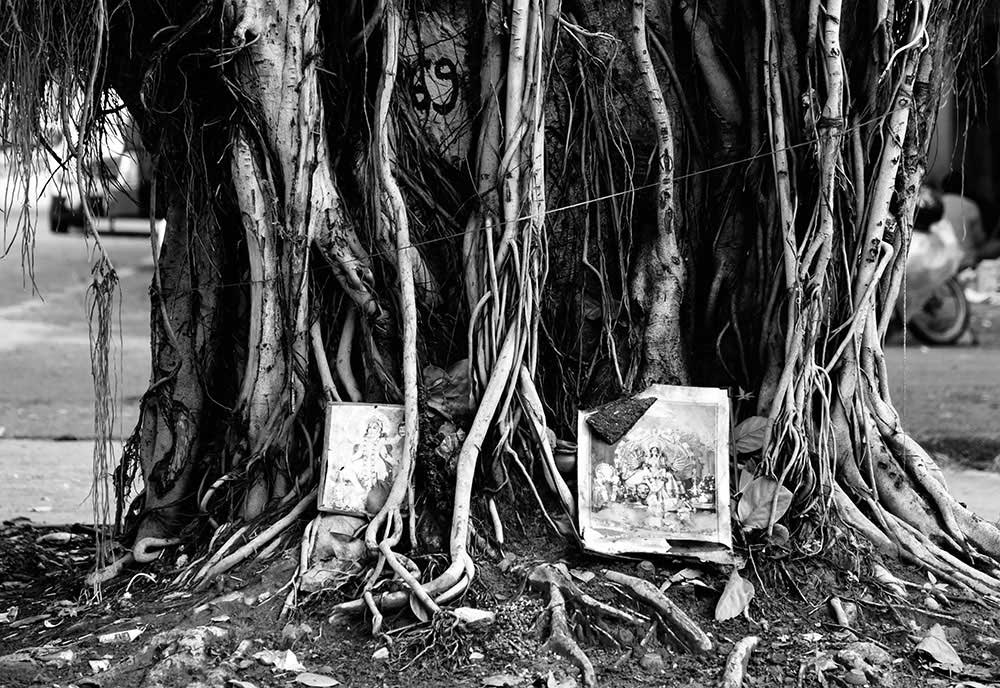

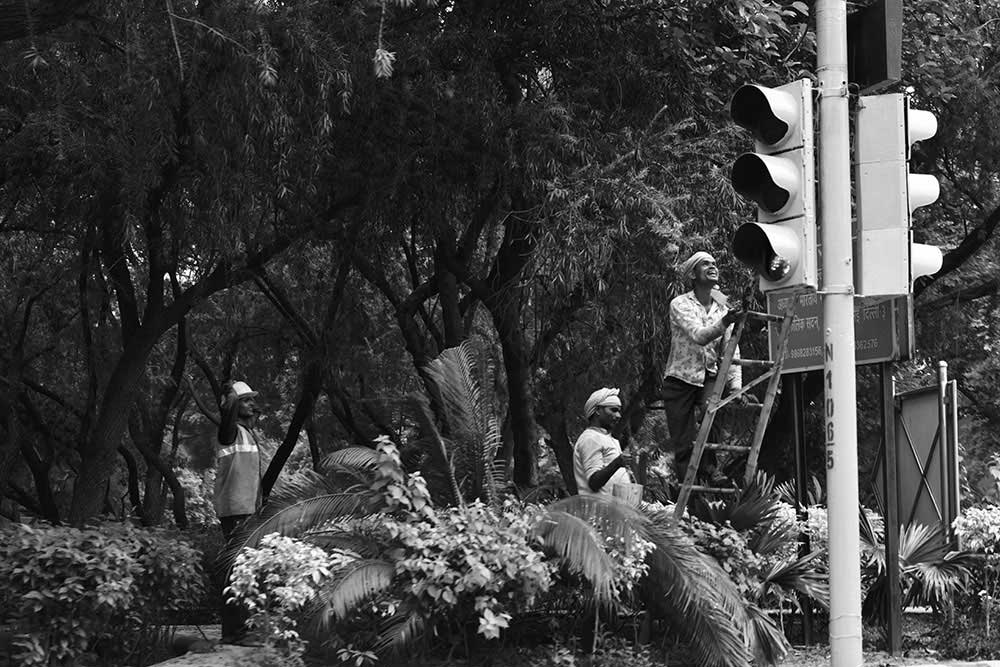

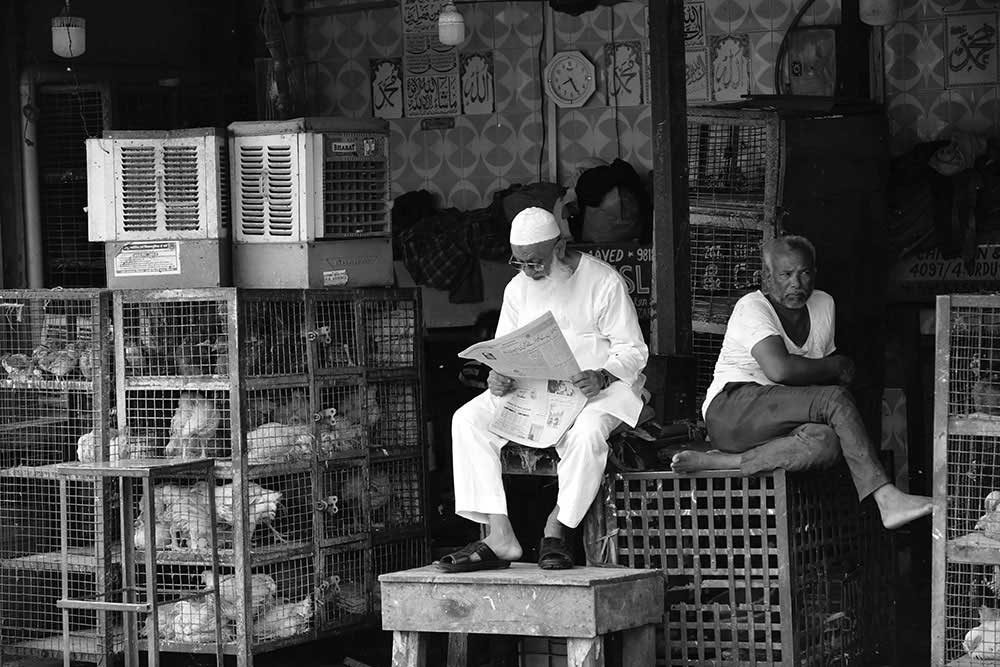

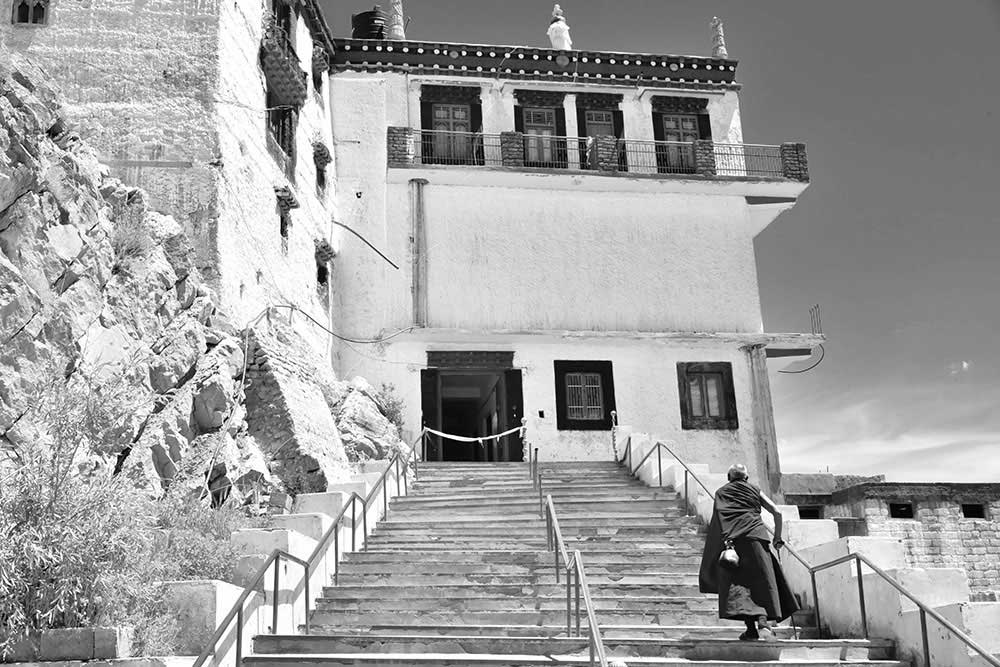

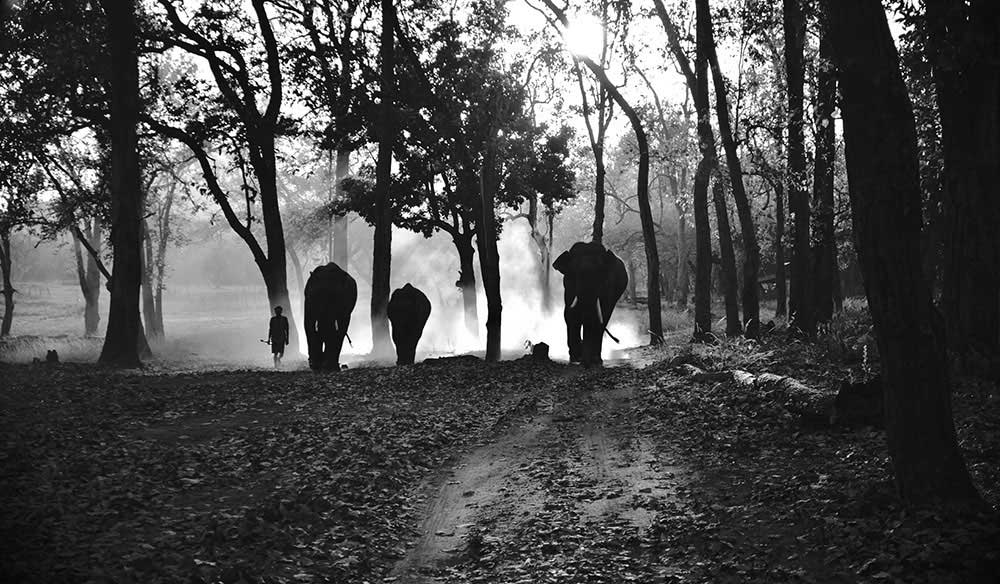

The twenty photographs’-long black and white series by Urvashi Singh convey the essence of her work when colours recede into the backdrop. A keen pursuer of vivid hues that illuminate the myriad streets of her homeland, the exercise of creating an exclusively monochromatic album was challenging for Urvashi especially because it called for an internal release of her inherent fixation with colour. Conveying one’s photographic work in black and white adds the particular challenge of maintaining a greater accuracy as far as light and composition is concerned because now, there is no added compensation provided by the adaptivity of colour, but rather, the compensation is further restricted by the definitiveness of black and white, and the abstractness of grey. This supposed frugality that is ordained by greyscale is actually a thoroughly enriching exercise for an artist, notes Urvashi, for it necessitates the resolve of determining the particularities of what one wants to convey to an audience in hues that do not permit carelessness, and yet, are the doors to the infinite characteristics of imaginative mystery. “There are two kinds of people in this world”, says Urvashi. “The first kind believe in there being black and white. The yin and the yang, for example. The good and the bad. The wrong and the right. And the second kind of people believe that there’s no black or white, but just an infinite spectrum of grey. Monochrome enables us to determine our own conviction of these parallel belief systems, or to juxtapose between the two based on our individual evolution as perceptive beings.”