Moszek Fagot was born on October 22 1891 in Warsaw. He was married, lived on Nalewki Street 9, and worked as a hat maker. In September 1939 German troops occupied Warsaw. On November 13, a 20-year-old Jewish man shot a Polish police officer and wounded another, in front of Moszek Fagot’s house. As a so-called “retaliatory measure,” the German occupiers shot 53 men who lived in that house. Moszek Fagot was spared for unknown reasons. But the living conditions in the ghetto were catastrophic, and on October 22 1941 Moszek Fagot was found dead in his apartment. It would have been his 50th birthday. [Link]

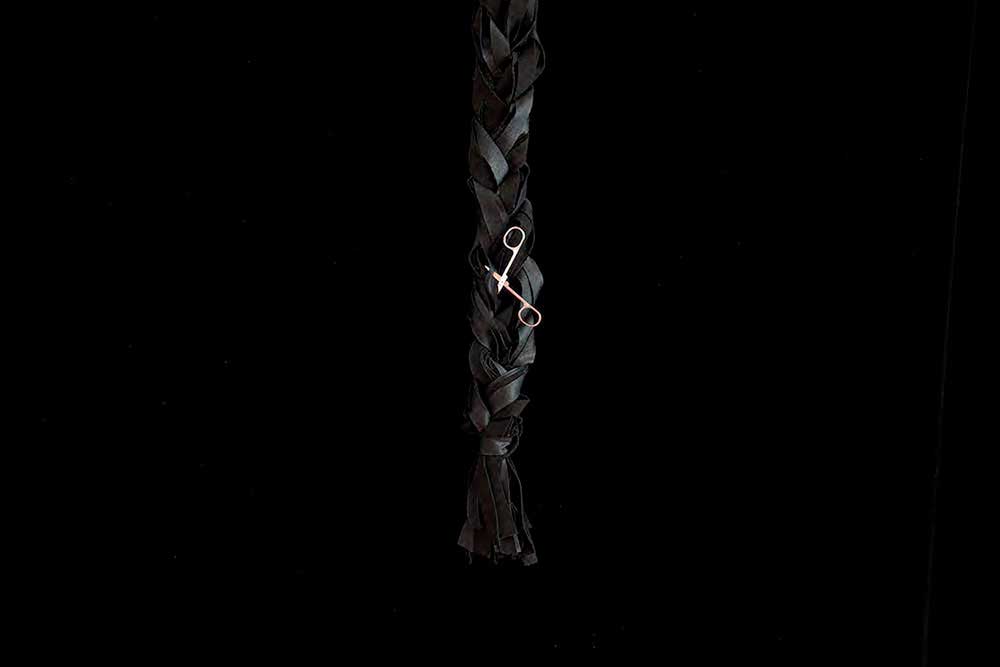

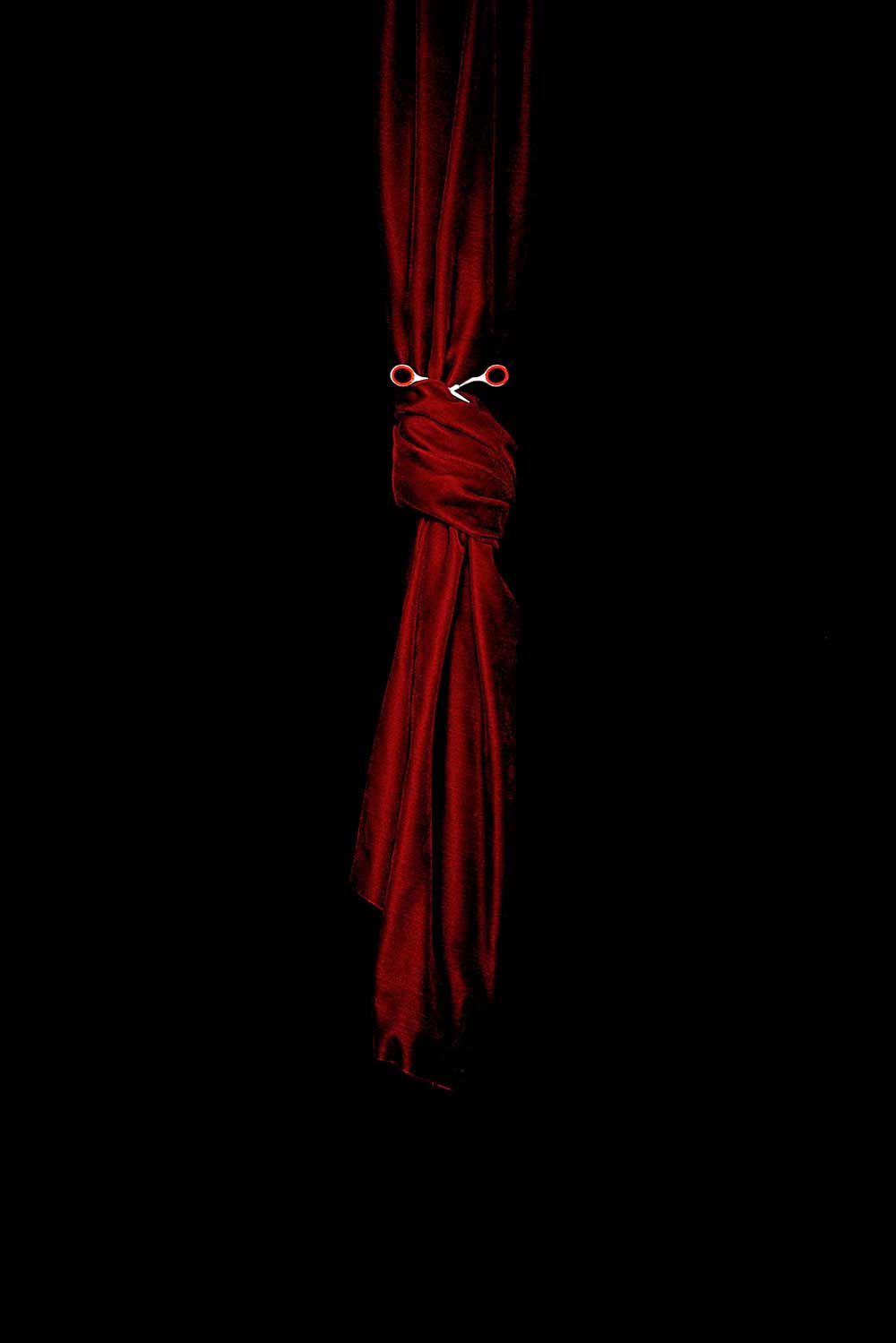

I like to think of my Great Uncle Moszek hovering somewhere between floors 8 and 12 of Nalewki Street 9 in the Warsaw ghetto. It is a safe place, this imagined placement of his body.

Down below the streets of the ghetto are not safe. A German soldier has been killed and revenge is about to be sought. Boots are heard on the ground, moving ever closer to number 9. The shattering of broken glass, wood and plaster heralds an imminent round up of what was to be 53 male Jews, including boys as young as 12 and 13 years old. If Moszek hovers – somehow invisible between floors – they will not catch him. Because they catch others. And yet this early transgression of genocide somehow left my Uncle Moszek untouched. He escaped this particular German act of retribution. Maybe I am right. Maybe he was hiding somewhere between floor and ceiling. Unseen .Kept alive. Safe. But two years later Uncle Moszek was found dead in his apartment on 22 October, 1941 . It was his 50th birthday. He did not die the day the Nazi soldiers rounded up his fellow dwellers but managed to survive a little while longer until the terror of ghetto living slowly took its toll. And then he died. I ignore that part. In my mind’s eye he oscillates somewhere between floors 8 and 12 in Nalewki Street 9. Alive and untouched by suffering.

Louise Fago-Ruskin

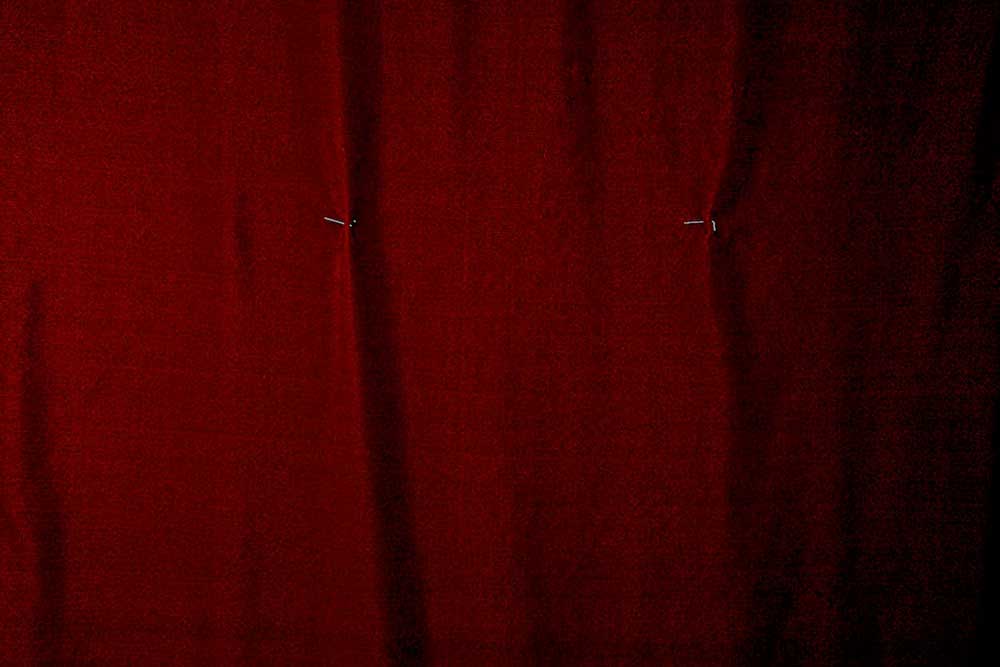

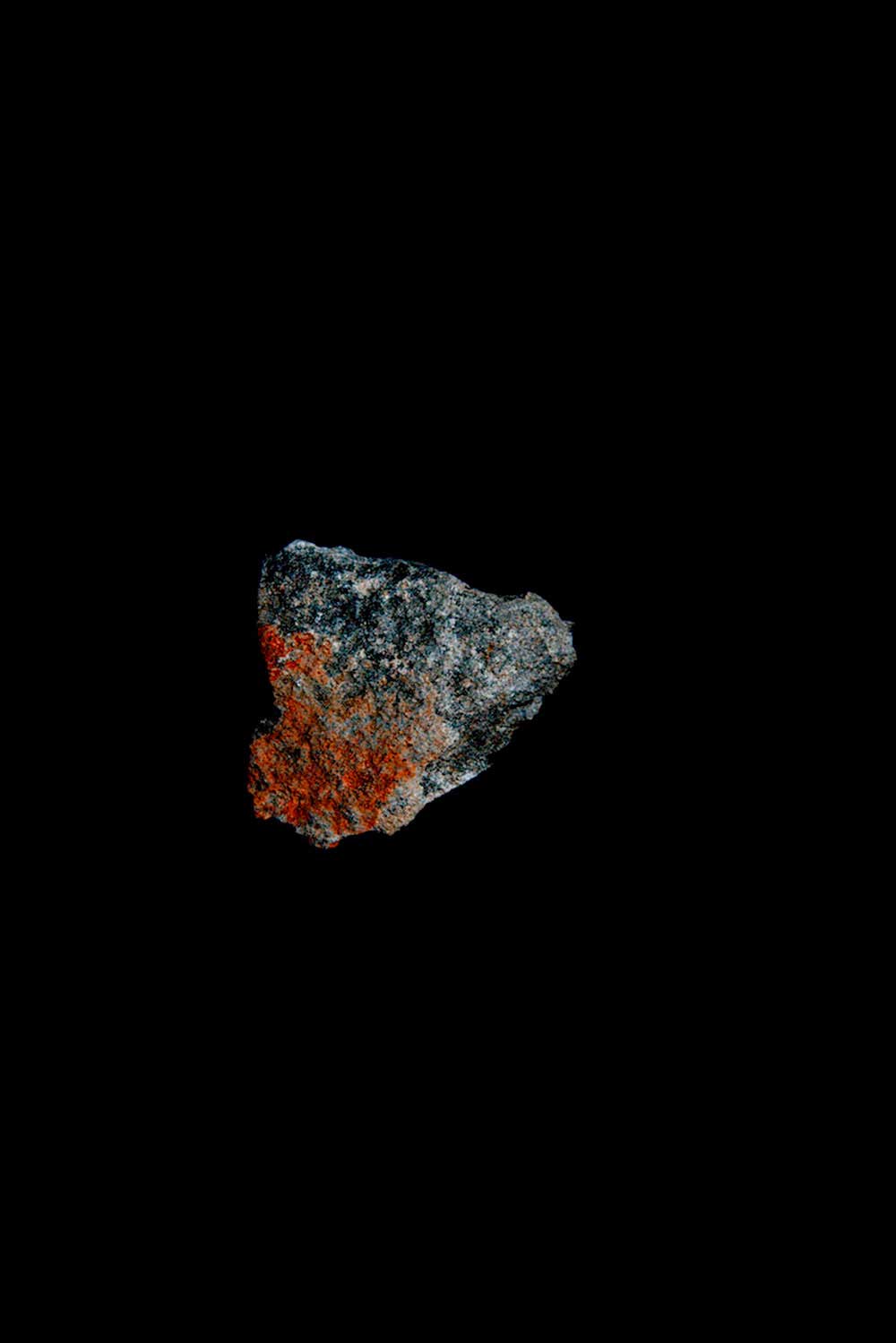

For the first time, Louise Fago-Ruskin begins to explore her own ancestral heritage in this ongoing body of work entitled Til All Is Correct. Remaining deeply committed to liberation of the unconscious – be that anger, longing, a kind of feverish imagining or the painful act of re-membering- she examines the links between her own personal life narrative and that of her Jewish-Russian heritage. Not only is the work a quest for connection and memorialisation, it challenges the cruel and nonsensical ways in which we measure the worth of an individual, a race, or a culture. Til All Is Correct it seeks to act as clarion-call for the collective re-assessment of our common relationships – one to the other -in an increasingly fractured and polarised world. [Officiale Wedsite]