SIBERIAN EXILES is a photographic triptych about the deportation of women and children from the Baltic States to remote parts of Siberia. Eyewitnesses recount the mass deportations, life in the Gulag camps, the organized resistance against the Soviet occupiers, and the beginning of the Cold War.

I traveled through the Baltic States to delve into historical archives and meet eyewitnesses to document their powerful life stories. Following in their footsteps, I embarked on long journeys through the former Soviet Union, capturing what I encountered: the landscapes, villages, cultures, and indigenous people, along with their own memories of life under Stalin.

Irena Valaitytė, *1928 Kaunas, Lithuania

In 1941 Irena was 13 years old. She, her mother and brother were deported from Lithuania to the Altai and later to the Laptev Sea. When they arrived in the arctic Irena was afraid she would freeze to death. She was constantly hungry for many years. Irena had to work 12 hours a day in the children brigade and received 300 gram bread a day. Her mother died because of the harsh circumstances. Irena and her brother had to survive on their own. In the 50’s Irena escaped on her own back to Lithuania.

In Kazakhstan, I sought to unravel the history of the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site and the connection between the Gulag system and the Russian nuclear project, which marked the beginning of the Cold War. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were forcibly annexed by the Soviet Union in June 1940, then occupied by the Nazis in 1941, and reoccupied by the Soviets in 1944. These nations endured nearly 50 years of Soviet rule until regaining independence in 1991. Mass deportations, executions, and arrests during these annexations left deep scars on their populations. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, old fears of Russian aggression have resurfaced.

In the first part of the triptych, I focus on the experiences of six Lithuanian survivors who, as children, were exiled to the Laptev Sea above the Arctic Circle during the first mass deportation in 1941. Their families were initially sent to the Altai region and, in 1942, were taken along with three thousand other Lithuanians to the Lena River delta in the Arctic to establish a fishing industry. This was an absurd task: the deportees were abandoned without protective clothing, food, or technical equipment. During snowstorms, they had to build shelters with their bare hands. Children were forced to work 12-hour days in exchange for a small piece of bread and soup. The Lithuanians shared this fate with deportees from Finland and Churapcha, a village in Yakutia, East Siberia. All suffered equally miserable conditions, enduring constant hunger and extreme cold. For many, exile was a death sentence.

Lithuanian and local Deportees in Yakutia, 1947 © Museum of Occupation and Freedom Fights Lithuania

The second part focuses on the organized resistance against the second Soviet occupation. When the Red Army advanced westward in 1944, expelling the Germans from the Baltic States, the Baltic people knew what awaited them under Soviet rule another wave of violence and repression. This fear fueled widespread resistance and a fierce determination to fight for independence. In 1944, an armed struggle against the Soviet occupiers began, lasting until 1956. The partisan movement enjoyed broad support from the population.

The third part tells the story of Marju, who was deported with her mother in 1949. While her father was arrested and sent to KarLag, a Gulag in Kazakhstan, Marju and her mother were sent to a kolkhoz in southern Siberia near the Kazakh border, where they were forced to work as farm laborers on the vast steppe. In August 1953, while out on the steppe, Marju witnessed clouds surging and boiling in the distance, followed by a storm and darkness. She had likely seen the detonation of the first hydrogen bomb.

Just 400 km away was the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, where mushroom clouds regularly rose into the sky. Between 1949 and 1989, the Soviet Union conducted a total of 456 nuclear tests there 111 on the surface and 345 underground.

Lenin sculpture in Yakutsk

About Claudia Heinermann

Claudia Heinermann (*1967) is a German-Dutch documentary photographer based in the Netherlands. She specializes in long-term projects that explore contemporary historical issues, political oppression, genocide, and the consequences of war. Her work has taken her to countries such as Bosnia, Rwanda, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Germany. To date, she has published seven photobooks and contributed to numerous publications both nationally and internationally. Her works have been acquired by various collections and exhibited in museums, galleries, and photography festivals. In 2015, she published her award-winning photobook Wolfskinder: A Post-War Story. Heinermann dedicated seven years to her trilogy Siberian Exiles, which was exhibited in 2023 at the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. In 2024, she received a state award the Cross of Terra Mariana from Estonian President Alar Karis for her project Siberian Exiles. [Official Website]

Nikita Solomonov, *1929, Yakutia, Soviet-Union

In the summer of 1942, there were 81 kolkhozes in the Churapcha region (Yakutia). 41 kolkhozes were completely deported to the Northern Regions. Food for the front was the propaganda. Men, women, children and the elderly had to build up a fishing industry, together with the Lithuanian exiles. Both lived and worked under equally miserable conditions that for many became a death sentence. Nikita was one of the lucky ones who survived the harsh living conditions and returned to Yakutsk.

Yakutsk

Yekaterina Yefremova, *1932, Yakutia, Soviet-Union

In 1942 Yekaterina’s family was deported to the Laptev Sea. Nearby their balagan was a smaller cabin where Lithuanian women and children lived. People kept dying there. Because they could not be buried in the frozen ground, they were thrown into the river or placed in cracks between rocks or in pits. Sometimes they saw bones blown about by the wind.

Yakutsk

Viktoria Tutoraitytė, *1950 in Trofimovsk, Soviet-Union (Lithuanian national)

In 1941 Viktoria’s parents were deported to the Altai and later to the Laptev Sea. The parents met each other during their exile and became a couple. Viktoria was born in 1950 in Trofimofsk, in the Lena Delta. In 1958 the young family moved to Yakutsk and decided to stay in Siberia. After the dead of her father in 1975 her mother moved back to Lithuania, three children followed her. Viktoria longed to follow her mother as well but had already a family on her own.

“No one has ever been convicted of the crimes against humanity committed by the Soviets. These crimes were openly discussed for the first time only after the Soviet Union’s dissolution. However, in Putin’s Russia, Stalin’s past is once again being concealed. This is why it is so important for me to preserve the stories that were hidden from us behind the Iron Curtain. They need to be heard to contribute to an accurate historiography.”

Viktoria’s house in Yakutsk

The frozen Lena river

The Lena river leads to the Arctic sea where the Lituanians and the people from the region of Churapcha were deported to. In the winter the river is used as an ice road.

Partisans in Lithuania, © Musueum of Occupations and Freedom Fights Lithuania

Forest in Latvia

Jānis Zemantis *1932, Latvia

Janis was active in the underground resistance. He was arrested in 1950, and was sentenced to 25 years in a prison camp in Vorkuta, where he had to work in the coal mines. He worked in three eight-hour shifts and received food twice a day: porridge and vegetable soup and the occasional piece of fish. He was always hungry and tired.

In July 1953, a few months after Stalin died, the Vorkuta uprising began. There were protests, and 18,000 prisoners refused to work. After two weeks of peaceful protest, the camp administration ended it by force. First, they arrested the saboteurs. Then they fired into the crowd, killing 64 people and injuring more than three hundred.

Forest in Latvia

Genutė Griškevičiūtė * 1928, Lithuania

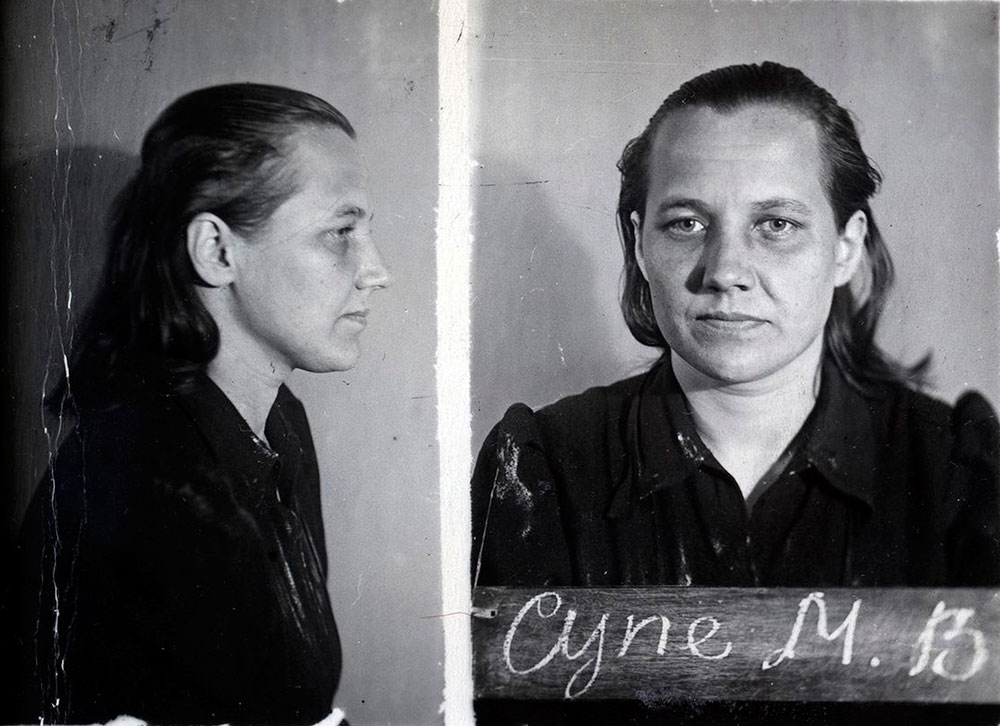

Genutė was involved with the partisans through her father and carried out assignments for them. After he died, she became their informant. She had to deliver or pick up packages, pass on messages, and gather news. She brought them things they needed, such as clothes, medicines, and bandages. In 1948, someone betrayed her. She was being watched by the NKVD and they tried to recruit her as a spy. Genutė didn’t want to betray the partisans but decided to play their game. Every week, she would report she hadn’t seen anything out of the ordinary.

Forest in Estonia

Lidija Lasmane *1925, Latvia

Lidija’s whole family was involved with the partisans from the very beginning. They had a farm which was a hiding place for the partisans. In 1946, Lidija was sentenced to five years in prison camp in Vorkuta and three years in exile. When she returned to Latvia, Lidija became a dissident and organized the smuggling of samizdat and tamizdat publications. She was arrested two more times, but never stopped resisting. In 2018, Lidija was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Mihalina Supe during her capture in 1954

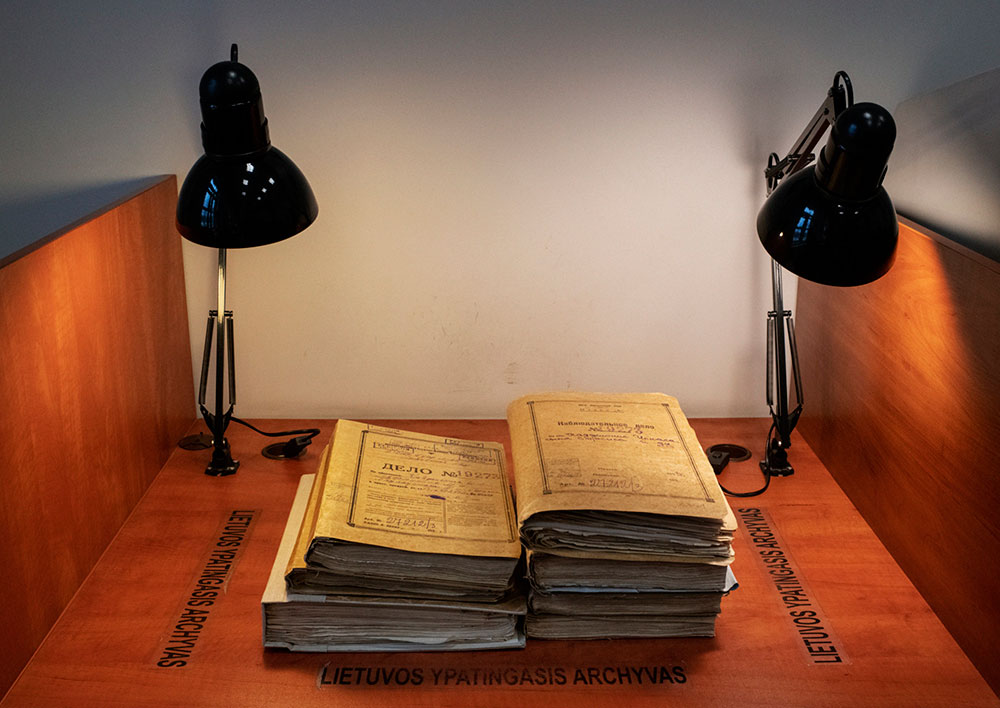

Partisan KGB Files about one partisan, Jonas Kadžionis

Vorkuta © National Museum of Lithuania

Marju Toom, *1939, Põltsamaa, Estonia

In 1949, Marju and her mother were deported to Siberia, close to the border with Kazakhstan. There on the fast steppe, she witnessed the detonation of the first hydrogen bomb in 1953. Her father was sent to a Gulag camp (KarLag) where he died in 1949.

KarLag Museum

KarLag was one of the largest labour camps in the Gulag system. An estimated one million political prisoners were incarcerated in camp until its closure in 1959. KarLag occupied an area of 300 x 200 kilometres and consisted of 26 subsections and 196 smaller prison camps. The former administrative building of KarLag is today a museum devoted to the memory of the victims of political oppression.

KarLag Museum

In 25 rooms of the Museum reconstructions have been made of prison cells, a torture chamber, an interrogation room and a hospital ward. The top floors are devoted to the history of the camp, the economic activities, and daily life.

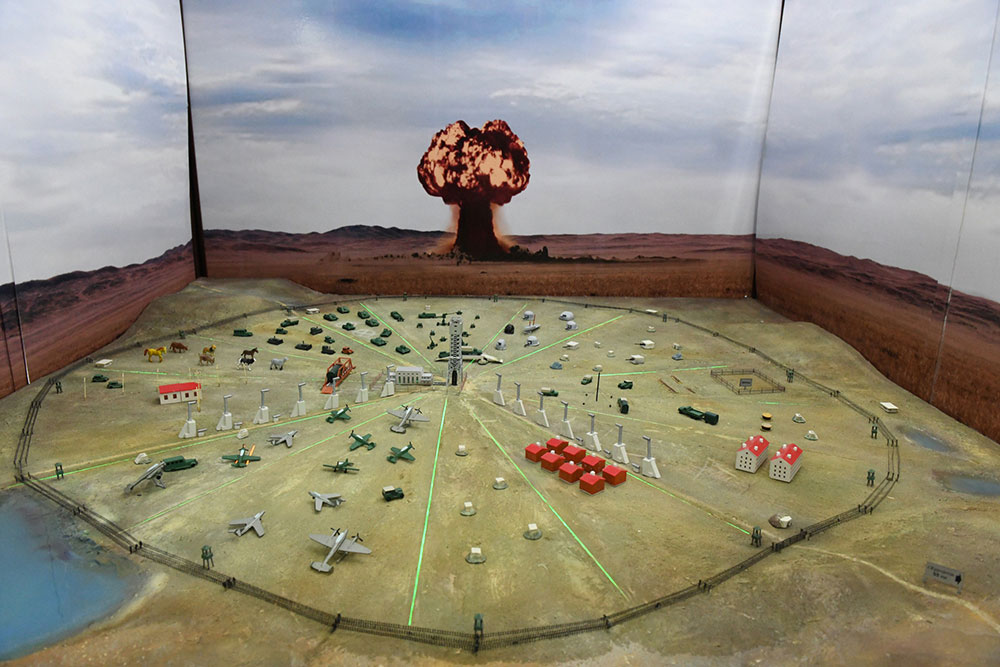

A scale model of Ground Zero at the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site Museum

Between 1949 and 1989, the Soviet Union carried out a total of 456 nuclear tests at Semipalatinsk, 111 of which on the surface and 345 underground. The Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site Museum shows which tests were carried out, where they took place, and with which nuclear techniques.

Instrumentation tower on Ground Zero

Instrumentation towers, also called “Geese”, were placed at different distances from Ground Zero. The towers contained monitoring equipment to measure the impact of the explosions and cameras to photograph and film the explosions.

Measurements with a Geiger counter on Ground Zero

Huge crater/ lake resulting from a nuclear explosion in 1963

Sholpan Satkombayeva, *1940, Semipalatinsk, Soviet-Union

Sholpan was a doctor and worked at Dispensary No 4, which was a secret institute to discover the effects of radiation. The test site was top secret and invisible on any map. It was a closed and forbidden territory. The D4 institute fell directly under the KGB and D4 workers had an obligation of secrecy.

Institute of Radiation Medicine and Ecology

After the closure of the Semipalatinsk test site in 1991 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Dispensary №4 was given a new name and a new role. While the institute had been a secret institution in the past, it was now accessible to the public. A rehabilitation programme was developed, and a department set up to provide specialised medical care to those who had been exposed to nuclear weapons tests.

Galina Golentseva, *1936, Semipalatinsk, Soviet-Union

Galina remembers many nuclear explosions from her childhood. The earth would shake, and it was very frightening. On one occasion she saw windows shatter and a mushroom rising into the sky. She graduated as an ENT doctor from the Semipalatinsk Medical Faculty and started in the children’s hospital in Ayagoz. There were remarkably many patients with leukemia.

A park in Semey with a collection of old Soviet statues

Veniamin Slednikov, *1947, Narjan-Mar, Soviet-Union

Veniamin was born near Novaya Zemlya, close to another nuclear test site. After completing his military service, he moved to Semipalatinsk (today Semey) and witnessed the underground nuclear explosions there. In 1987 he was sent to Chernobyl to help after the disaster. He worked there as a driver. After two months it turned out that the radiation level in his car was too high to be allowed to drive any further. That was the moment he first learned about the dangers of radioactive radiation.