Victoria comes from the art curating profession. From first-hand experience, I’d say not all of us who curate -but certainly a part of us- do it for the same reason as the creators: to communicate. We have a need to communicate how we see things, and we do this through engaging with and promoting the work of artists which we firmly support, with which we share a same outlook and a same code of understanding.

This marvel; the fact that individuals from disparate contexts and origins, can occasionally come to have a point of confluence, is the same marvel that can occur when an anonymous spectator is able to enter into the very core of an idea or a project. It is because of this that Victoria has seamlessly transitioned from curation to creation.

Her searching and reflexive gaze, as the great spectator that she is, today is extended through the camera. Direct, a missile in image form; full of poetry, of carefully crafted composition and beauty. In her images there is that certain something which makes us draw shuddering breaths, churning the stomach, touching that which is most sensitive. In these works, the purest feeling of love and affection can morph into the sharpest and most painful. Certainties of love are turned on their heads and become a fear of loss, a fear that those same certainties might disappear. These are the affects, links, knots and bonds with which Victoria crafts, her starting point being her family, her immediate environment. She submerges them in water, a medium the human animal has often poured its uneasiness into. For some, a friendly medium which brings back good memories. For others, one full of tension, impotence, drowning or insecurity.

An olive fermenter from the family business is repurposed as a swimming pool in which to submerge her whole family, from her closest relatives to second and third lines of ascendants and descendents. From this results a collection of suggestive images, which communicate a lot about what Victoria -out of water- could intuit about each of them.

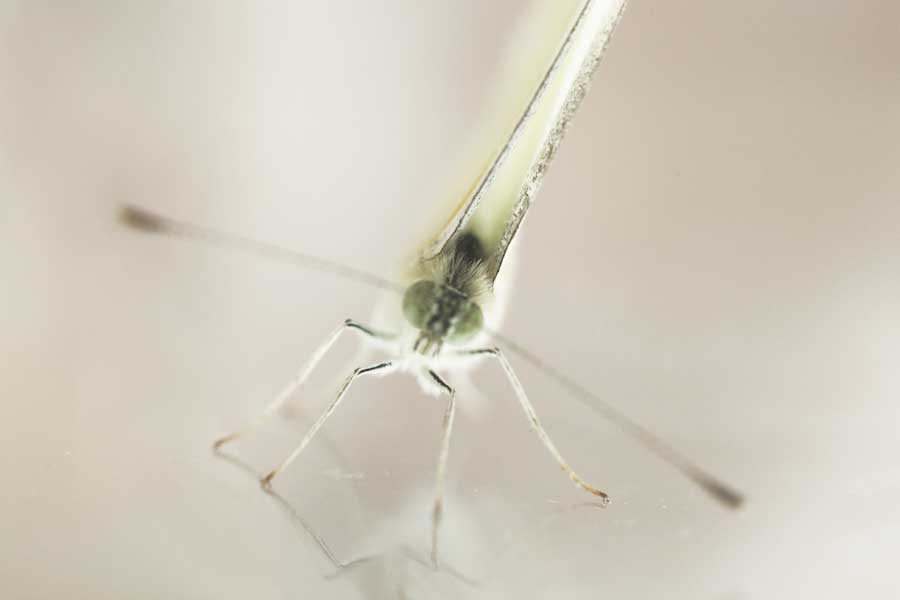

These images contain aesthetic parallels with Daniel Canogar’s series Vórtice (2011). In it, Daniel reflects on humanity’s behaviour, habits and its consequences. Characters appear suspended in water, surrounded by rubbish. It is worth noting the expressivity of these figures, overwhelmed by their aqueous medium, in a solitary struggle to escape and survive. The series Seres, by Victoria has a similar premise. To live in the countryside is to share a space, a medium if you will, with the insects and reptiles with dwell in one’s surroundings. Victoria “captures” them (later freeing them) in a transparent glass receptacle, which has the same role the swimming pool in Familia has, becoming also the medium to negotiate. A process of patient mutual observation ensues. Some animals relax, others squirm: their fears and insecurities augmented within the glass jar. As with the family, they are to be captured in images which are a mixture of the sharp and faded, and others where colours and chiaroscuros share a stage. These moments and poses captured by the lens are transcendent; both in their own right and in stark contrast with the images from Familia, and make us understand that our nature –human- is no different to that of the animal. In fact, we may as well be speaking of the same thing. [Official Website]

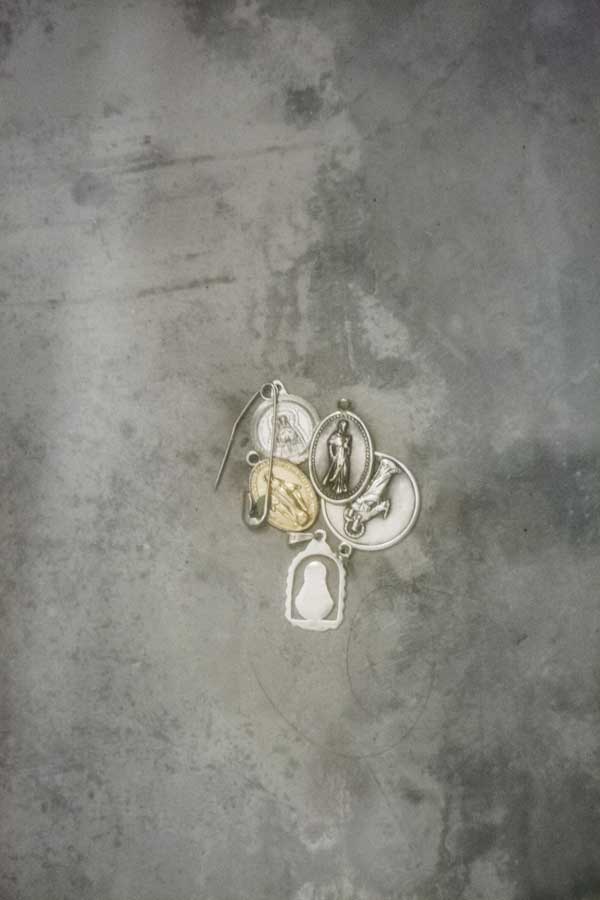

Familia opens like Pandora’s Box. It emerges with an initial goal that with time acquires further ramifications. Some of its most recent extensions are the recent immersions of her mother, her aunts and of she herself. These immersions open to a much more personal reading, centred on the mother-daughter relationship. This link has become strained with the death of her father, and from an urgent need to cling to the mother. Mother, generous and complicit, and also scared of water, agrees, and unexpectedly there emerge new connections. During the immersion a collection of family medallions collected over years, full of cultural and religious significance, is momentarily lost to the swimming pool. She had always kept them attached to her underwear, in order to feel them nearer. It is here where the object becomes a link, like an extension of oneself; is imbued with value and significance, defining us as individuals. The submerged images of this series evoke those of Dutch photographer Ellen Kooi, who through her narrative –and highly choreographed- photography, generates in her models a series of poses which leads them to mental states of great emotional intensity. Works such as Almere – Ophelia (2006) Duinmeer – lissen (2012), Schoten – waterlelies (2014) show us submerged characters with the flair of the great Flemish masters of the past.

With regard to the aunts, Juana y Lola, is a three way nexus. One of them suffers from Alzheimers, the other has become her guide, and Victoria observes in order to capture a mimesis that unfolds, for between them words are redundant. Their hand, their bodies, their clothes and their identities become one. In this work it is easy to find reminiscences of the Viennese artist Gustav Klimt, in similarities apparent between the way the aunts are dressed and extremely ornamented clothing that can be found on his canvases, the contrasts and vibrations of colour –specifically his poses- in the dance of affection, full of emotion which is his magnum opus, The Kiss (1907). In these sinkings, the gestures of all of them are charged with power, a desire to enclose, to assure, to comfort. Consciously or unconsciously we are part of a place, of the house, of the family, of parents, sharing air, an environment, feeling different, though our similarities are more abundant. It is something of such immense complexity that it comes across extremely simple. [Text: Antonio Jiménez – Gallerist and curator]