The scars of war are deep and long lasting. That is particularly true of the Vietnam War. An entire generation along with their families, children, friends, and society at large on both sides still carries the legacy of that war.

12,000 square miles of Vietnam were sprayed with Agent Orange and other defoliants resulting in a massive ecological damage and drastically unbalancing the food chain. Rural society was uprooted. In spite of (or maybe because of) Curtis LeMay’s comment that: “…we’re going to bomb them back into the stone age…”, the destruction of farm land resulted in large scale resettlement in urban areas providing an energetic work force for the rapid industrialization that has occurred.

For a variety of reasons, I missed the Vietnam War. In March of 2016, I had the chance to see Vietnam for myself. I had been invited to join a tour by a college friend. He, in turn, knew the editor of a memoir of a veteran who had done two tours of duty with the Air Cavalry in Vietnam in the late 60s. This memoir provided the outline of our tour.

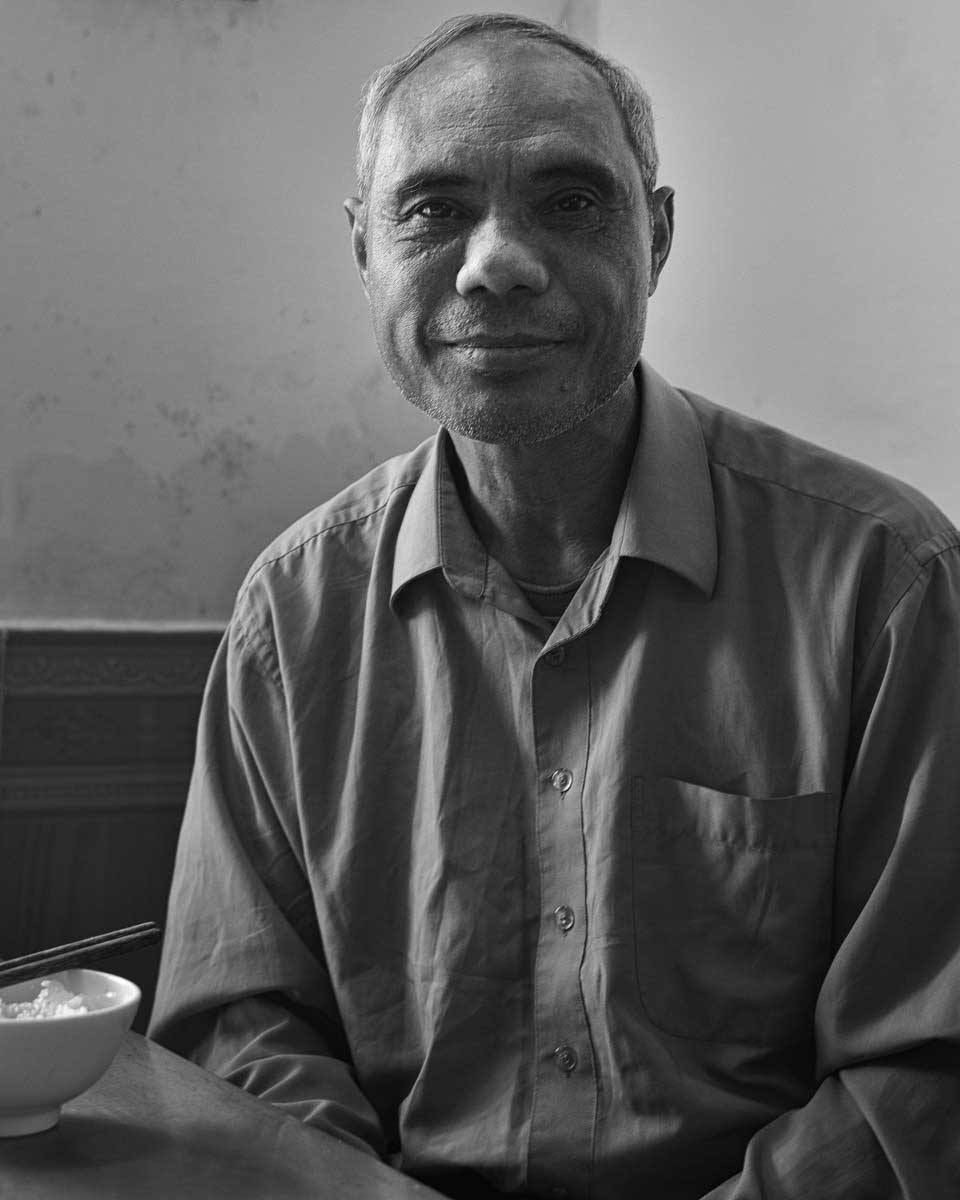

We moved from South to North visiting abandoned US airbases, searching out battle sites, and interviewing people involved in NGOs that provided assistance to the Vietnamese injured during the war. We encountered survivors from both sides of the conflict and listened to their stories. The last stop was Vietnam Friendship Village that was established through the efforts of George Mizo, a US veteran of the war, and others involved in the reconciliation movement. The founding vision was to provide a residential facility to aid Vietnamese children and veterans. Much of this assistance has addressed problems related to the effects of Agent Orange.

The complex is located in a suburb of Hanoi–that grey transitional zone between the traditional rural society and the spreading world of exposed concrete residential towers, air pollution, and motorcycles. It provides care to 100-120 children and about 40 adults at any one time. In spite of the Friendship Village’s grim bureaucratic buildings and environment, it is a place of healing and promise.

About Kip Harris

For nearly 30 years, I was a principal of FFKR Architects in Salt Lake City. My wife and I now live in a heavy timber cottage built in 1823 over looking St. Margaret’s Bay in a small fishing village in Nova Scotia, Canada. [Official Website]