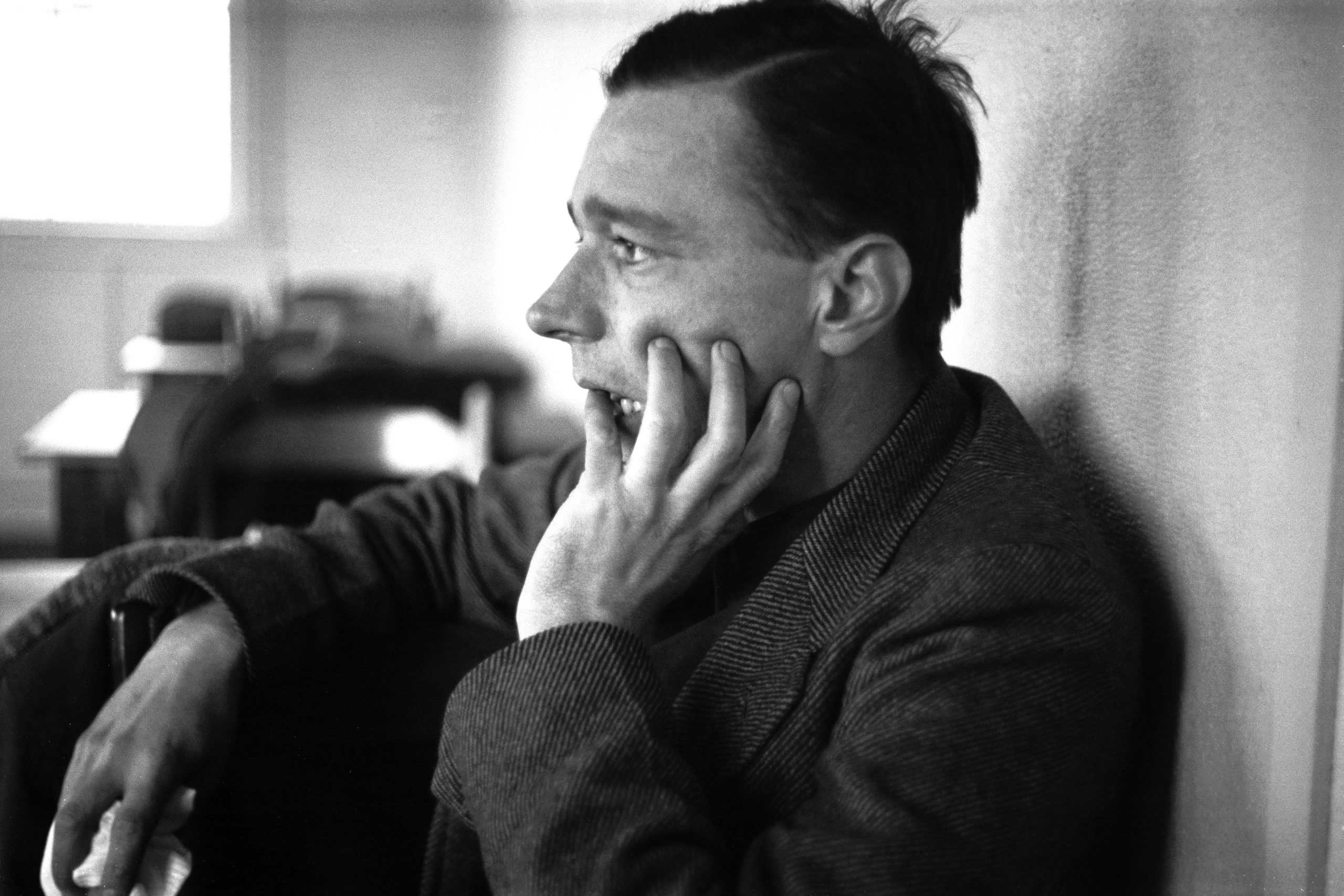

Walker Evans wrote with his photographs. A frustrated writer with years of studies in literature at the best colleges and universities, he poured his literary restlessness into his images, photographing the details of daily life that went unnoticed by others and describing with great sobriety and conciseness the American society of the Great Depression. He photographed the extraordinary from the ordinary.

Walker Evans was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on November 3, 1903, to a wealthy family. As a child, he moved to Chicago because of the work of his father, who was a creative editor at a major advertising agency. He spent his youth in the suburbs of Chicago, Illinois, and in Toledo, Ohio, where his family moved again in 1914, when he was 11 years old.

There, his father fell in love with a married neighbor and, when she finalized her divorce in 1918, he abandoned his family and began a relationship with the woman. Perhaps that abandonment was the trigger of Walker’s personality: complicated and contradictory.

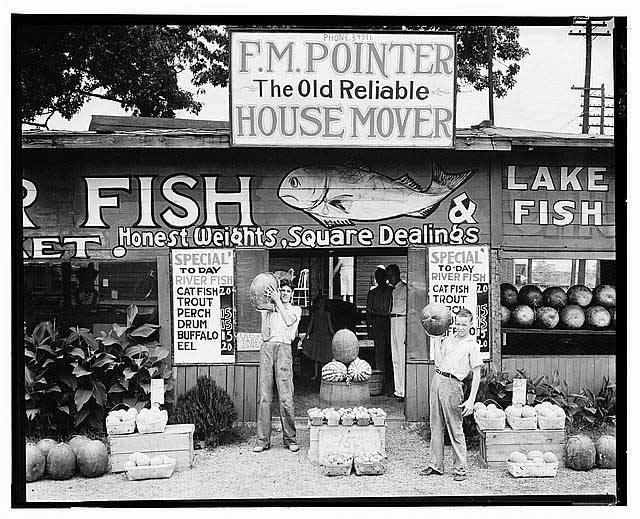

With his father engaged in graphic advertising, Evans had been able to develop a particular relationship from a very young age with the mass iconography produced for the vernacular sector (postcards, posters, posters and advertising signs, lottery tickets, tickets for vehicles public). Documents and objects of popular culture that Evans will collect throughout his life and that will influence his way of doing photography from the point of view of content and spirit.

With the camera, it’s all or nothing. You either get what you’re after at once, or what you do has to be worthless. I don’t think the essence of photography has the hand in it so much. The essence is done very quietly with a flash of the mind, and with a machine. I think too that photography is editing, editing after the taking. After knowing what to take, you have to do the editing.

As a teenager, he already had a Kodak Brownie camera and learned how to develop and print his photos on his own. In January 1919, he and his family moved to New York. He studied at Williams College in Massachusetts, where he became a ‘pathological bibliophile’. But within a year, he dropped out.

In 1922, at the age of 19, he studied literature and languages at Phillips Academy, Andover, also in Massachusetts. In 1923 he travelled to Paris to continue his studies of literature at the Sorbonne, but with the idea of becoming a writer and mixing with the intellectual life of the Paris of the 1920s. During that one year he spent at the Sorbonne, he endeavored to master the French language and native body language, so that he would not be taken for a tourist.

It is in Paris where he began taking pictures with a Kodak Vest Pocket. He was influenced by the French poets of the 19th century, because he sees in photography a means to adapt the poet’s vision and meticulously show a daily and contemporary America.

In 1927, he returned to New York, where he began to take photos non-stop. He begins to take his first photographs with a 6 x 12 camera; snapshots of simple and direct scenes of everyday life. During that time, he became friends with artists and writers and kept in touch with the progressive currents.

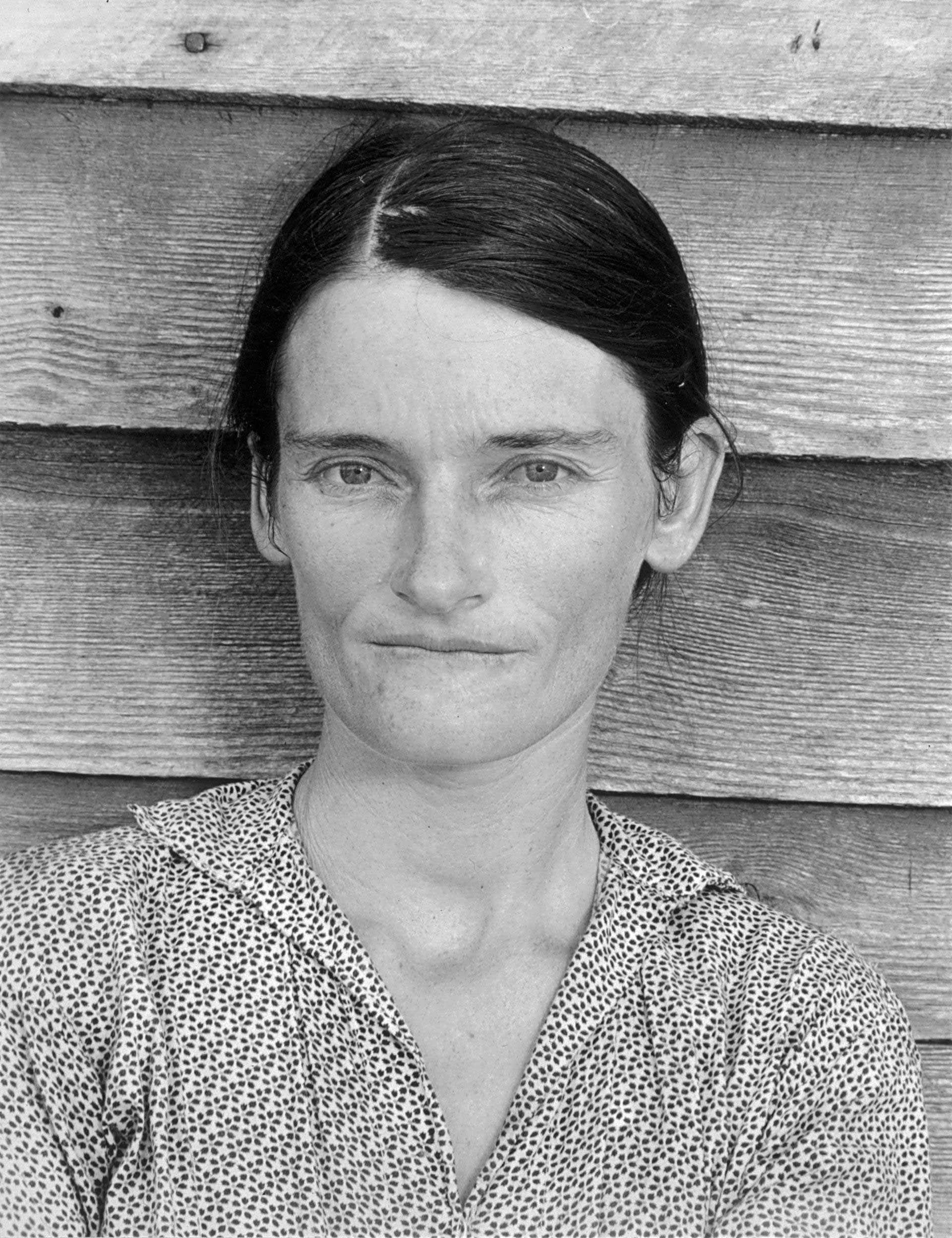

The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative. By their fewness, and by the importance of the reader’s eye, this will be misunderstood by most of that minority which does not wholly ignore it. In the interests, however, of the history and future of photography, that risk seems irrelevant, and this flat statement necessary.

Then, with a 15 x 20 camera, he travels through US cities, together with Lincoln Kirstein, a young intellectual, who was part of the MoMA’s advisory board and played an important role in the development of American cultural life. The use of large format cameras differentiated him quite as a documentary photographer, since he did not use Leicas (unlike his colleagues), his pictures were more deliberate and thoughtful.

In 1930, at the age of 27, his first photos were published: three photographs in the poem ‘The Bridge’, by his poet neighbor, Hart Crane. His photos were published in Hound & Horn, Architectural Review and Creative Art.

In 1933 he travels to Havana, and the photographs he takes there appear in the book ‘The Crime of Cuba’, written by Carleton Beals. That year he met Ernest Hemingway and presented his first exhibition at the MoMA, entitled ‘Walker Evans: Photographs of Nineteenth Century Houses’. It consists of 39 photographs of architectural types that deal with the transformation of the American identity.

Incidentally, part of a photographer’s gift should be with people. You can do some wonderful work if you know how to make people understand what you’re doing and feel all right about it, and you can do terrible work if you put them on the defense, which they all are at the beginning. You’ve got to take them off their defensive attitude and make them participate.

Three years later, hired by Roy Stryker, he joins the team of photographers of the Farm Security Administration, where Dorothea Lange also participates, to document the redevelopment process carried out mainly in the southern United States. He became a storyteller and condensed ideas into calculated images with the purpose of inviting the viewer to engage.

In 1936, Evans joined a project for Fortune magazine – in which he would collaborate for 20 years – to document the lives of Alabama’s peasants, along with writer James Agee. This report would then be rejected by this magazine, but published five years later in the book ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’.

Throughout his life, he received numerous mentions and acknowledgements of his work, including two grants from the Guggenheim Foundation and a third one from the Mark Rothko Foundation. He died in 1975 in the city of New Haven.