In 2017, I retired from a career in independent school teaching and leadership to pursue photography full-time my true north since college.

When I am not traveling, I split my time between street photography in New York City and rural projects in the Hudson Valley.

Over the last several years, this effort has been rewarded by exhibitions in several New York City and regional galleries, and by features in magazines, including articles or portfolios in B&W Magazine, Der Spiegel, Inspired Eye, Chronogram, and Dodho Online.

My work has been purchased by several private collectors and is part of the permanent collection of the Duncan Miller Gallery in Santa Monica, CA, which named me to their “Hot 100” list of photographers for two years in a row. However, the most fulfilling work I’ve done recently is to volunteer as a photographer for Village Health Works a clinic and hospital, a high school and pre-school, and several economic cooperatives located in southern Burundi.

The story of Village Health Works began in 1993, when Burundi suffered the same genocidal violence that notoriously afflicted Rwanda. Only in Burundi, the war lasted for more than a decade, took the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, and reduced the country to one of the poorest and hungriest in the world. Deogratias Niyizonkiza, aka Deo, then a medical student in Bujumbura, barely escaped with his life and ended up in New York City as a refugee. He struggled for months with homelessness and low-wage jobs until he was eventually befriended by a generous couple who gave him a home and sponsored his education. After several years of university training in public health and medicine including a close association with Paul Farmer and Partners In Health Deo returned to his home village of Kigutu to found Village Health Works. The land and labor needed to create the original campus, infrastructure, and four-mile access road were all donated by the local community of subsistence farmers.

Today, with the crucial support of an army of mostly American donors and private foundations, Deo’s vision has burgeoned into the construction of a $20 million women’s teaching hospital that is beginning to bring modern healthcare and with it, the foundation for future prosperity to the area. Deo’s story is the subject of Tracy Kidder’s book, The Strength That Remains.

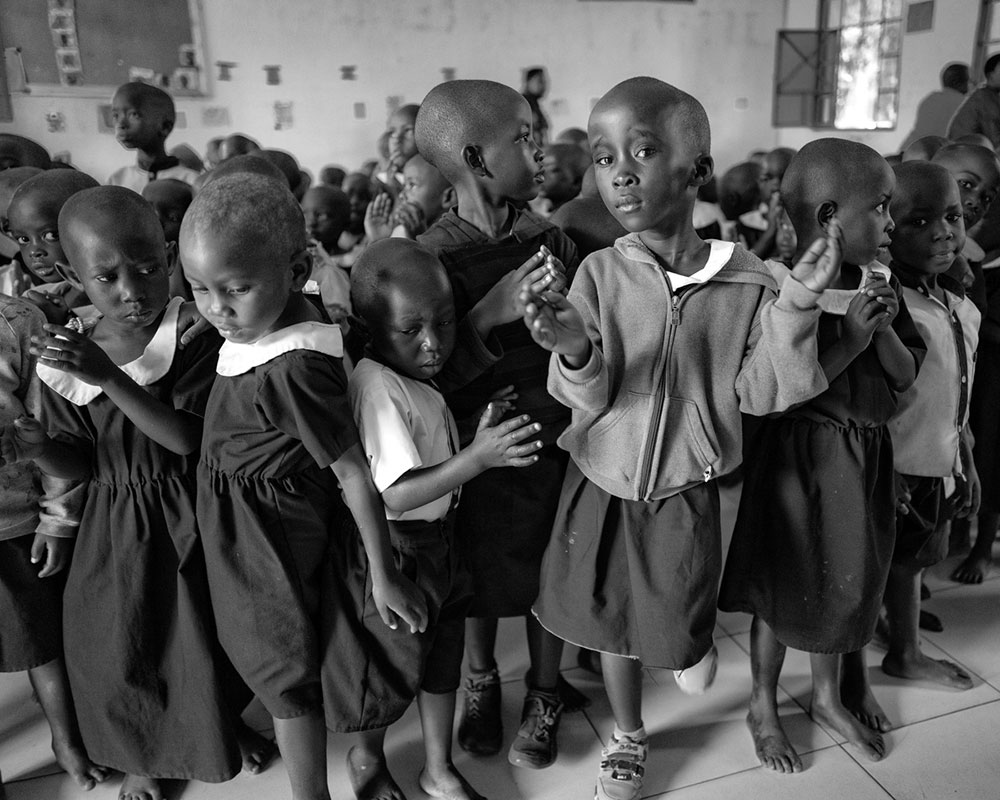

The photographs in this portfolio focus on the schools and the clinic itself. A pre-K is run by VHW, which has also contributed classrooms and funding to an École Fondamentale or “Ecofo,” a public elementary-through-high school. Both are a lifeline for the community. Young children walk miles in plastic sandals and arrive at the pre-K, often hungry and listless, where they are greeted first with music and dance performed daily by the VHW band, and a bit later, by breakfast.

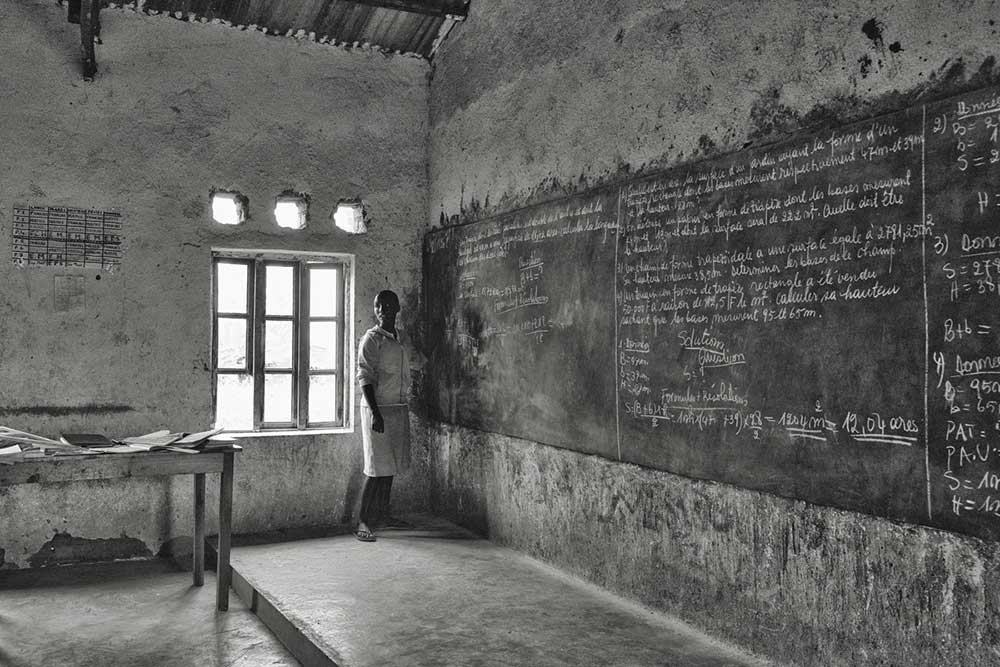

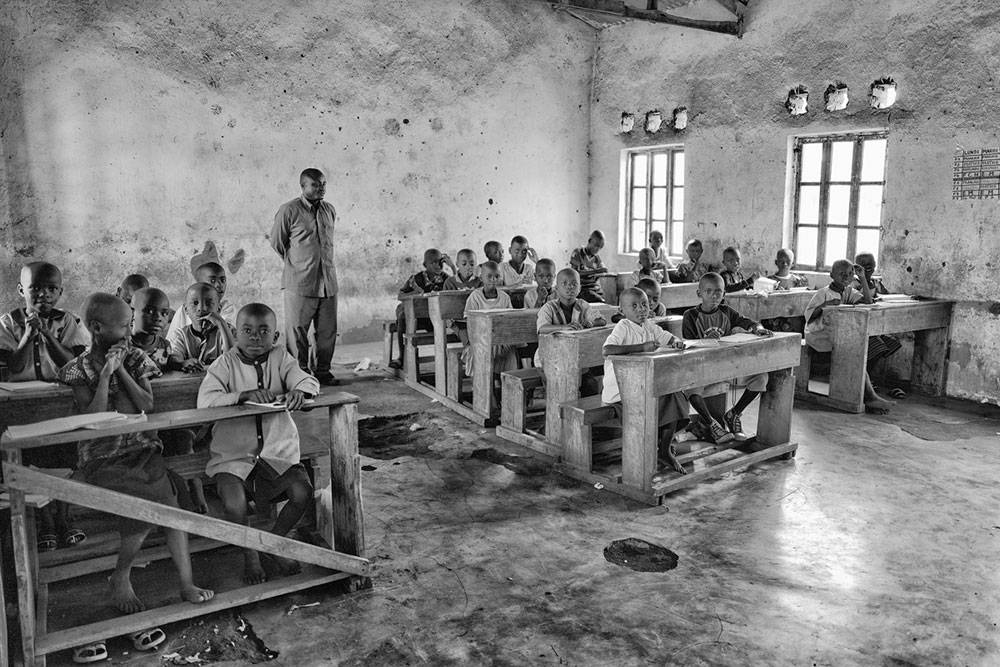

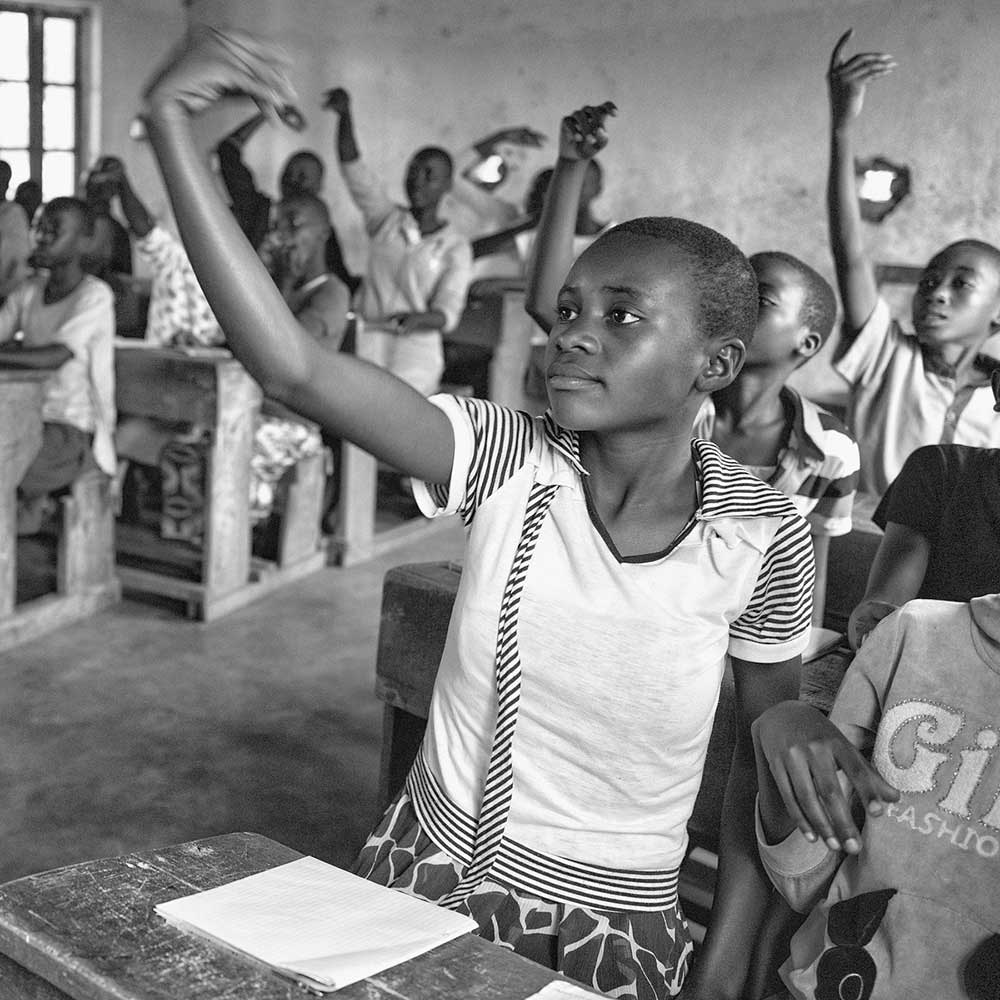

Although they have since been replaced with modern spaces, the classrooms in 2019 were primitive open windows, loose brick floors, and blackboards with layers of unerasable text, like some ancient palimpsest. The pedagogy was full-frontal lecture, delivered mostly in French, hour after hour, one subject after another until late in the day. But the kids were alert, eager to participate when asked, and deeply respectful of their teachers. In a world where poverty and hunger are ubiquitous, any chance at an education that might lead to college and a life beyond subsistence farming is precious.

Until the hospital was completed, the clinic was the sole source of crucial medical care for the people of Kigutu and its surrounding area. Every morning, dozens of people mostly women with young children arrived for intake and triage. Many came from miles away, having walked on trails and rough roads through the night with two or three children in tow, to arrive before the clinic opened. These women were striking always impeccably dressed, as if for church, out of respect for the clinic and the doctors who cared for them.

Once admitted, they sat on simple cots for hours with their children around them, silent or talking quietly with neighbors. There was nothing to distract or entertain the kids no books, no games, certainly no TV or devices of any kind. And while some were very ill, injured, or malnourished, even the healthy children asked for nothing while they waited their turn to see a doctor. In both the schools and the clinic, I was humbled by this quiet strength and grit.

Thirty years ago, the people in Kigutu were slaughtering each other in a rage of intertribal violence, aggravated by a century of colonial and postcolonial misrule and injustice. Today, their remains have been gathered together in a star-shaped memorial garden at the heart of a stunning tropical campus, maintained by the people of this same village a community now almost fully employed by Village Health Works.

In the early days, when Deo was hiring the first workers, a candidate for a security position confessed that Deo would never hire him if he knew what crimes he had committed in that same village ten years before. Deo responded, “I know what you did, and that’s exactly why I want to hire you.” That striking faith in the human spirit is powerfully materialized in the new hospital and school, and in Village Health Works’ ageless motto: “Where there’s health, there’s hope.” [Official Website]