William Eggleston decided to take the risk of breaking the rigid stereotypes of his time, exposing himself to the censorship of those who had been his referents. However, the artist showed that his subject-matter of the banal, day-to-day and sometimes even ugly was something that could catch and baffle spectators. While Walker Evans spoke of “breathtaking typographic quality”, Eggleston spoke of “excellent tonal quality”, an aspect that made him a distinguished photographer.

Commonly recognized as one of the fathers of color art photography, he was born in Memphis, United States on July 27, 1939. His father was an engineer and his mother, the daughter of a prominent local judge. He grew up under a wealthy southern home in Sumner, Mississippi.

His father died during World War II, so his education was left in the hands of the maternal grandfather, Joseph Albert May, a noted judge with a love for photography. At the age of 10, Willian had his first camera: a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye.

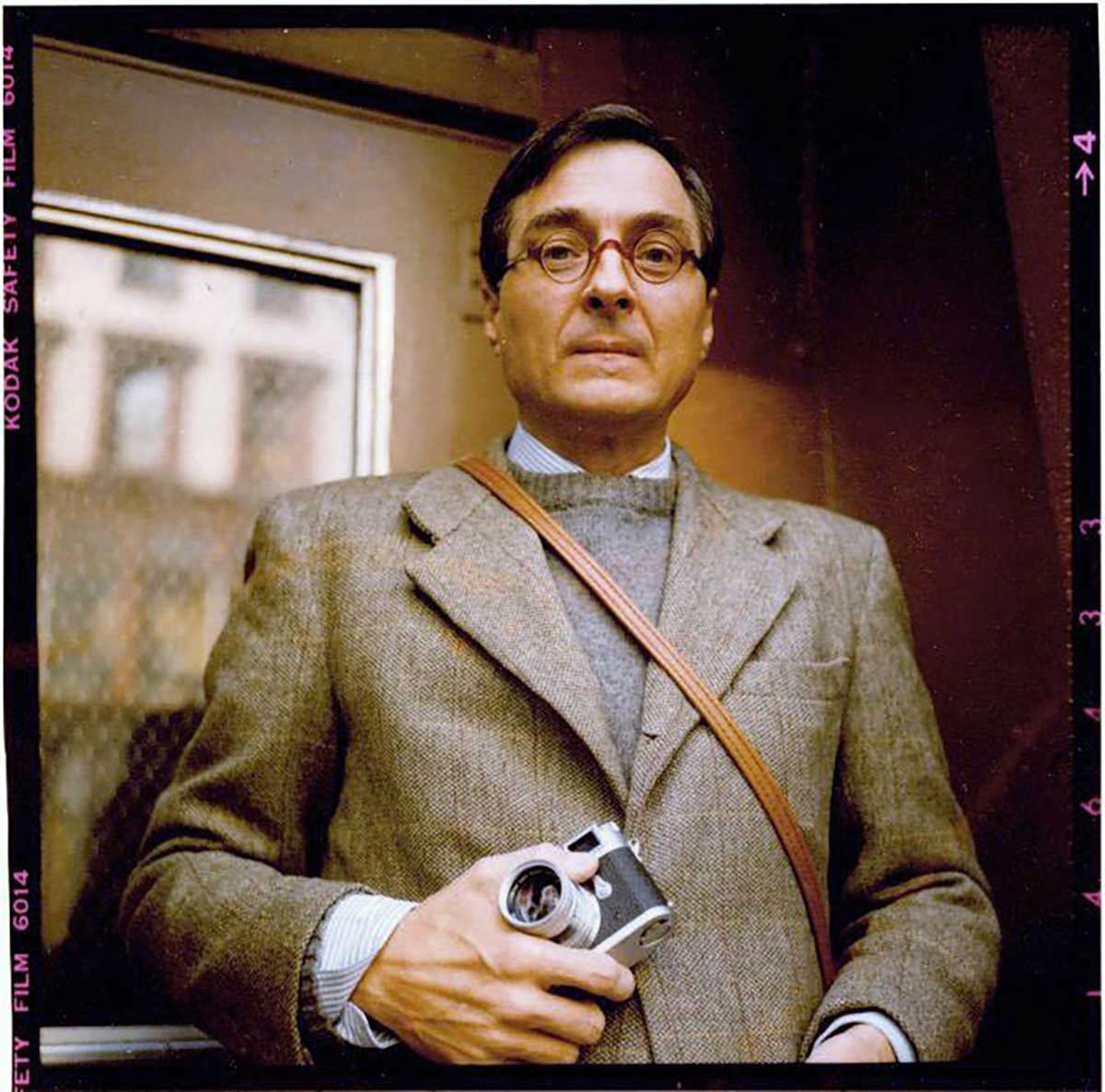

During his youth, he attended Vanderbilt University for one year, Delta State College for a semester, and the University of Mississippi for about five years, without completing his studies. In spite of everything, those university years left their mark on him: in an art class, he met the abstract expressionism of the mid-fifties, and his interest in photography began. He purchased a Leica camera and started to experiment with his new interest.

A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.

In his early stages, he took black and white pictures. At that time, the serious photographers like Ansel Adams or Edward Weston worked in monochromatic. On the other hand, and like the rest of the photographers of his generation, he was deeply influenced by other well-known photographers of the moment; the books of Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank were his models of inspiration.

Shortly after, in 1965, he abandoned the monochrome style to experiment with color technology, until then considered a characteristic of commercial work. Rebel to the core, he contravened unwritten rules of photography: “If you wanted to make art, you had to take pictures of beautiful, black and white subjects.” At this time, color photography was only for amateurs, not for consecrated photographers with artistic intentions.

That criteria evidently did not matter to him: he worked in areas close to Memphis, taking color photographs of ordinary subjects. He chose to photograph everything around him but without a registration intention, but openly artistic, at a time when documentary photography reigned in the photographic trade.

I’ve always assumed that the abstract qualities of [my] photographs are obvious. For instance, I can turn them upside down and they’re still interesting to me as pictures. If you turn a picture that’s not well organized upside down, it won’t work.

In 1969 his work was known by John Szarkowski, a photographer, curator, historian, and critic, who was so impressed that he suggested to the photographic committee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York to acquire some of William’s works.

Between 1973 and 1974 he taught at Harvard University, and discovered the process known as Dye-transfer. Eggleston was struck by the degree of saturation of colors and inks obtained in the laboratory. One of his best-known works is done with that technique, The Red Ceiling of 1973, which the artist himself considers as one of his best works.

In 1976, with the support of Szarkowski, his work was exhibited at the MoMa. He became the first photographer to make a full color exhibit in that museum; a real turning point in the history of photography. The exhibition was demolished by critics, who accused him of vulgarity for his use of “tacky” colors.

I don’t have a burning desire to go out and document anything. It just happens when it happens. It’s not a conscious effort, nor is it a struggle. Wouldn’t do it if it was. The idea of the suffering artist has never appealed to me. Being here is suffering enough.

The New York Times itself had defined the performance as “the worst show of the year”. Decades later, the show’s reputation was radically revised. Curators and critics of today are able to see the real value of that exhibition. In addition to becoming famous for the use of color, the factor that most struck the criticism was the choice towards the banal.

Eggleston’s legacy is endless. It can be seen in the hundreds of thousands of color photographs of nondescript and inconsequential situations that circulate through the immense world of the internet. American cars, road signs, normal objects: these were Eggleston’s main subjects. His style was studied and followed by great artists such as Gus Van Sant, Sofía Coppola, Jeff Wall and it even became of great impact for directors of the caliber of Wim Wenders.

He received the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography in 1998 and a Sony World Photography Award in 2013. William currently lives and works in Memphis.